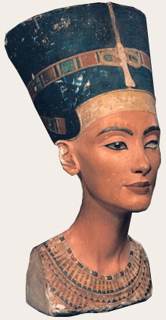

Matchless and unmatchable—there she stands at the very dawn of the finer arts. Interesting that Nefertiti’s bust was found in the sculptor’s workshop; but then a number of things at the end of her life seem to have been incomplete, proper burial included, and there’s something nice about this incomparably elegant head lying in an artist’s studio surrounded by limestone chips—a dusty place, but a workplace, and not nearly as stuffy as your average tomb.

Matchless and unmatchable—there she stands at the very dawn of the finer arts. Interesting that Nefertiti’s bust was found in the sculptor’s workshop; but then a number of things at the end of her life seem to have been incomplete, proper burial included, and there’s something nice about this incomparably elegant head lying in an artist’s studio surrounded by limestone chips—a dusty place, but a workplace, and not nearly as stuffy as your average tomb.

How the sculpture came about is not widely known, but it seems to have all begun around 1341 BC. That’s when her royal husband Akhenaten went on an image-breaking orgy, destroyed countless sacred effigies of falcons, and jackals, and crocodiles, and announced that from then on men must worship one god only—the sun. The novelty of this religious upheaval was all very exciting; but afterwards the queen fell into a severe post-iconoclastic depression.

“What is wrong, my queen and my beloved? said Akhenaten.

It’s the soothsayers, she answered.

What sooths did they say? he inquired.

They said the Nile would not rise, and it hasn’t. They said your chin would grow ever longer, and it has. They said that destroying the sacred images of our gods would be a disaster—and who knows? Perhaps it will be as they say.”

To this the king had no answer. Despite weeks of potent spells and incantations, the Nile remained sullenly in its bed. He knew he was no Adonis, and though large sums from the royal treasury had been spent, it was clear that Egypt’s most gifted cosmetic surgeons could do nothing to shorten his jaw. As for the new doctrine that there should be one god and one god only… it was obviously a huge gamble that might not pay off. The people liked their jackals, scarabs, and stuff.

So he did what he had done in the past to lift the wilting spirits of his exquisite queen. He went out and bought her a spectacular hat, and a gorgeous gold necklace, and then he told the court sculptor to get some suitable limestone, and to sharpen his chisels, and prepare for work. The rest is history.

* * *

Artistic history anyway. And from a strictly formal standpoint it is notable that even by 1341 BC certain broad conventions for portrait busts were well established: head, neck, shoulders sometimes as far as the upper arms, after which the line cuts steeply in at right angles to the supporting pedestal. Earlier than Nefertiti, back in 2700 BC, there’s a head from Gizeh showing that at that date the rules were less clear: the fellow’s neck ends abruptly as if his head were chopped off.

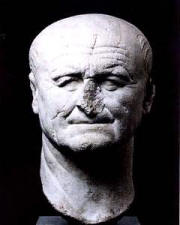

In Roman antiquity you couldn’t be sure a man had even lived if he left no portrait, while a Roman family could barely be said to exist without a complete domestic gallery of sculptured likenesses. Suetonius reveals the obscurity of Vespasian’s background by saying that the Flavian house was “without family portraits”, though he added that this was not necessarily a disgrace.

Rome was a real mess when Vespasian took over in 69 AD—civil war had laid waste the Capitol, buildings were shattered, rubbish was everywhere, lawless soldiers were on the loose, and Roman matrons were misbehaving with their slaves. We read that Vespasian “began the restoration of the Capitol in person, was the first to lend a hand in clearing away the debris, and carried some of it off in a basket on his own head.”

Rome was a real mess when Vespasian took over in 69 AD—civil war had laid waste the Capitol, buildings were shattered, rubbish was everywhere, lawless soldiers were on the loose, and Roman matrons were misbehaving with their slaves. We read that Vespasian “began the restoration of the Capitol in person, was the first to lend a hand in clearing away the debris, and carried some of it off in a basket on his own head.”

He looks as if he had the right head for the job. Strong enough to be a solid plinth for a wobbling nation. His unrelaxed expression also suggests the right mind and character—the mouth firm, the lips pursed, the eyes direct and fearless. Vespasian was smart enough to have survived at Nero’s court, while at the same time, further afield, he displayed his soldierly talents by knocking sense into fractious malcontents all the way from Judaea to the Isle of Wight. As Emperor he resolved to restore order, and made a start by purging the Legions of their more useless troops. Suetonius:

He let slip no opportunity of improving military discipline. When a young man reeking with perfumes came to thank him for the commission he had been given, Vespasian drew back his head in disgust, adding the stern reprimand: ‘I would rather you smelled of garlic.’

And he revoked the commission too. Compare the tough realism of the man in Vespasian’s portrait bust with the wandering eyes and sensual fatigue of Commodus (Emperor from 180 to 193 AD), a “debauched dog” according to Gibbon, and the nonpareil of imperial decadence. Numberless depravities must lurk beneath those lids. But the historian of the fall of Rome shows a psychologically subtle understanding of the Emperor’s character. Gibbon:

And he revoked the commission too. Compare the tough realism of the man in Vespasian’s portrait bust with the wandering eyes and sensual fatigue of Commodus (Emperor from 180 to 193 AD), a “debauched dog” according to Gibbon, and the nonpareil of imperial decadence. Numberless depravities must lurk beneath those lids. But the historian of the fall of Rome shows a psychologically subtle understanding of the Emperor’s character. Gibbon:

“Commodus was not, as he has been represented, a tiger born with an insatiate thirst of human blood and capable from infancy of the most inhuman actions. Nature had formed him of a weak rather than a wicked disposition. His simplicity and timidity rendered him the slave of his attendants, who gradually corrupted his mind. His cruelty, which at first obeyed the dictates of others, degenerated into habit and at length became the ruling passion of his soul.”

* * *

Around 1530 Hans Holbein the Younger made these studies of Lady Margaret and Sir Thomas Elyot, using black and colored chalks on a pink paper. Sir Thomas himself wrote a pioneering book on health, and is famous for a quotation about wildfowl: “Fesaunt excedeth all fowles in sweetnesse and holsomeness, and is equall to capon in nourishynge.” Perhaps. I have not eaten pheasant, but did once try to eat a sage grouse in Wyoming. Fiercely muscular, it tasted more like sage than grouse.

Around 1530 Hans Holbein the Younger made these studies of Lady Margaret and Sir Thomas Elyot, using black and colored chalks on a pink paper. Sir Thomas himself wrote a pioneering book on health, and is famous for a quotation about wildfowl: “Fesaunt excedeth all fowles in sweetnesse and holsomeness, and is equall to capon in nourishynge.” Perhaps. I have not eaten pheasant, but did once try to eat a sage grouse in Wyoming. Fiercely muscular, it tasted more like sage than grouse.

Sir Thomas also said some sensible things about painting. In his humanist treatise The Boke Named the Governour he defends teaching young people the observational skills of the portrait artist. These are seen as a useful way of obtaining an accurate description of the world around us—a doctrine close to the heart of both Karl Popper and his friend Ernst Gombrich. Pupils with a talent for art, he argues, will find it happily reinforces their other skills, whether reading, writing, or speaking. (Elyot’s text below is sometimes paraphrased, and the spelling has been updated.)

Sir Thomas also said some sensible things about painting. In his humanist treatise The Boke Named the Governour he defends teaching young people the observational skills of the portrait artist. These are seen as a useful way of obtaining an accurate description of the world around us—a doctrine close to the heart of both Karl Popper and his friend Ernst Gombrich. Pupils with a talent for art, he argues, will find it happily reinforces their other skills, whether reading, writing, or speaking. (Elyot’s text below is sometimes paraphrased, and the spelling has been updated.)

Everything that portraiture may comprehend will be to him delectable to read or hear. And where the lively spirit, and that which is called the grace of the thing, is perfectly expressed, that thing will be more persuasive in a painting than in writing or speaking.

Drawing was a vital part of the new cartographic understanding of the physical world:

Experience we have in learning of geometry, astronomy, and cosmogrophy, called in English the description of the world. I dare affirm that a man shall more profit, in one week, by figures and charts, well and perfectly made, than he shall by only reading or hearing the rules of that science by the space of half a year at the least…

In Sir Thomas (and also in Holbein) we find a prologue to Enlightenment. The purity of the realistic impulse to be found in Thutmose, the sculptor of Nefertiti, is here serving larger designs. These emphasise an objective attitude toward the world, and the kind of humane detachment regarding human folly that comes to full maturity in Shakespeare. Holbein’s engagement with his subject is entirely professional. And that includes Lady Margaret.

* * *

In contrast, Bernini’s bust of Costanza Bonarelli is deplorably unprofessional. Not artistically, of course, but Costanza was the wife of one of Bernini’s assistants, and not content with cuckolding her husband he proceeded to insult the poor man as well. Then when she turned her affections toward Bernini’s brother Luigi all hell broke loose, blood was spilled (some of it Costanza’s) and Pope Urban VIII stepped in before anyone got killed. He took it upon himself to advise Bernini to get married. The artist did so, his marriage in 1639 to Caterina Tezio lasted 34 years, and they had 11 children.

A spritely note by Jonathan Jones in The Guardian tells us that this sculpture of Costanza is “as light as air. Or desire. Bernini has made more than a ‘speaking likeness’. He has made an intimate monument to secret moments, a sculpted memento of his lover, whose marble reality dissolves, when you chance on her among the stony dead, into breath, life. Bernini’s genius for motion is dedicated to making his lover live forever. Her wild hair and loose clothes speak of energy and passion. He has caught her mid-glance, mid-conversation, perhaps before or after sex.’

A spritely note by Jonathan Jones in The Guardian tells us that this sculpture of Costanza is “as light as air. Or desire. Bernini has made more than a ‘speaking likeness’. He has made an intimate monument to secret moments, a sculpted memento of his lover, whose marble reality dissolves, when you chance on her among the stony dead, into breath, life. Bernini’s genius for motion is dedicated to making his lover live forever. Her wild hair and loose clothes speak of energy and passion. He has caught her mid-glance, mid-conversation, perhaps before or after sex.’

Here I feel Mr Jones has allowed himself to be carried away—Bernini’s muse has become his own. And if this is the arousing effect “the stony dead” can have on a man after nearly 400 years you can see what Costanza’s husband was up against. But perhaps Jones is onto something: she does have an air of anxious interruption, she’s fidgety, very much alive… there’s a feeling this pose won’t last long.

* * *

Not everyone liked this liveliness. At about the age of 18 or so Bernini produced the dazzling Apollo and Daphne, caught at the instant Daphne’s limbs were turning into a laurel tree, with her skin becoming bark and leaves sprouting in places from her upraised hands. But grave men like Sir Joshua Reynolds complained that what Bernini was trying to do in stone was better done with paint. There was talk about “truth to materials”, and about the theatre being a better place for dramatic events and emotions to be expressed through art. The attitude seemed to be that if God had meant stone to be used this way he would not have made it in blocks.

Not everyone liked this liveliness. At about the age of 18 or so Bernini produced the dazzling Apollo and Daphne, caught at the instant Daphne’s limbs were turning into a laurel tree, with her skin becoming bark and leaves sprouting in places from her upraised hands. But grave men like Sir Joshua Reynolds complained that what Bernini was trying to do in stone was better done with paint. There was talk about “truth to materials”, and about the theatre being a better place for dramatic events and emotions to be expressed through art. The attitude seemed to be that if God had meant stone to be used this way he would not have made it in blocks.

Sir Joshua looked at the face of Bernini’s David, tensed as he prepares to use his sling, and found much to censure: “As in Invention, so likewise in Expression, care must be taken not to run into particularities. Those expressions alone should be given to the figures which their respective situations generally produce.” He has a point of course. We don’t want Nefertiti looking like that. Or the Lady Margaret. Or even Costanza. For Nefertiti especially we want the timeless serenity of eternal aesthetic grace.

Sir Joshua looked at the face of Bernini’s David, tensed as he prepares to use his sling, and found much to censure: “As in Invention, so likewise in Expression, care must be taken not to run into particularities. Those expressions alone should be given to the figures which their respective situations generally produce.” He has a point of course. We don’t want Nefertiti looking like that. Or the Lady Margaret. Or even Costanza. For Nefertiti especially we want the timeless serenity of eternal aesthetic grace.

But the reasons Sir Joshua gives for his dislike of “particularities” brings us to something a little different, and not quite so defensible. He’s concerned about social status. Top people should be represented looking like top people—dignified, wise, strong, handsome, kindly, and not to be messed with impertinently by the lower orders. Sir Joshua, a man who made it is his business to get on with top people, painted an awful lot of them looking this way. But I’d happily trade a hundred of those respectful portraits of 18th century aristocrats for just one copy—for just a decent print—of Hogarth’s Shrimp Girl. It’s more me.

But the reasons Sir Joshua gives for his dislike of “particularities” brings us to something a little different, and not quite so defensible. He’s concerned about social status. Top people should be represented looking like top people—dignified, wise, strong, handsome, kindly, and not to be messed with impertinently by the lower orders. Sir Joshua, a man who made it is his business to get on with top people, painted an awful lot of them looking this way. But I’d happily trade a hundred of those respectful portraits of 18th century aristocrats for just one copy—for just a decent print—of Hogarth’s Shrimp Girl. It’s more me.

An Australian writer living in Sydney, Roger Sandall is the author of The Culture Cult (2001), a study of romantic primitivism and its effects. His work has appeared in a number of places including Commentary, The American Interest, Encounter, The New Criterion, The American, Sight and Sound, Quadrant, Art International, The New Lugano Review, The Salisbury Review, Merkur, Mankind, Visual Anthropology, and Social Science and Modern Society.

An Australian writer living in Sydney, Roger Sandall is the author of The Culture Cult (2001), a study of romantic primitivism and its effects. His work has appeared in a number of places including Commentary, The American Interest, Encounter, The New Criterion, The American, Sight and Sound, Quadrant, Art International, The New Lugano Review, The Salisbury Review, Merkur, Mankind, Visual Anthropology, and Social Science and Modern Society.