A sense of danger is a wonderful thing. Like Darwin said, don’t leave home without it. A sense of danger — or at the very least a prudential wariness in unknown territory — warns you of the bear in the cave, the croc in the creek, the shark beyond the breakers. Most ocean-going yachtsmen find it useful too. A sailor who doesn’t understand the grim warning “worse things happen at sea” could sail into serious trouble round Cape Horn.

That’s why Jessica Watson’s voyage is interesting. Will something happen to her? Tens of thousands are following her blog as Ella’s Pink Lady, a sturdy Sparkman and Stephens 34 sponsored by Ella Baché, heads down across the Pacific to the Southern Ocean.

Jessica Watson

Jessica’s plainly a nice kid and having a great time — but is she well-advised? When New Zealand-born mum Julie said on television that sailing around Cape Horn was no more dangerous than crossing the street (or did she say that crossing the street was more dangerous?) you began to wonder. Is there something in the water? Or is it just the Antipodal Mind?

Few of us think clearly when badgered by hostile interviewers, and that might have had something to do with it. But it’s an unusual claim, especially when the sailor is a 16-year-old girl, not strongly built, who indeed looks more of a child. In contrast to mum Julie, others with rather more sailing experience show more respect. After surviving a tumultuous night off Tierra del Fuego among the breaking seas and invisible rocks known as “the Milky Way”, Joshua Slocum wrote in 1898:

“Hail and sleet in the fierce squalls cut my flesh till the blood trickled over my face; but what of that? It was daylight, and the sloop was in the midst of the Milky Way of the sea, which is northwest of Cape Horn, and it was the white breakers of a huge sea over sunken rocks which had threatened to engulf her through the night.

It was Fury Island I had sighted and steered for, and what a panorama was before me now and all around! It was not the time to complain of a broken skin. What could I do but fill away among the breakers and find a channel between them, now that it was day?

Since she had escaped the rocks through the night, surely she would find her way by daylight. This was the greatest sea adventure of my life. God knows how my vessel escaped.”

“The greatest sea adventure of my life.” That was Captain Joshua Slocum’s measured judgment, aged 52, after 30 years of wrecks, strandings, dismastings, and many storms in all the seven seas. At Cape Horn, having eventually found smooth water among the islands near Cockburn Channel, he climbed the mast to survey the wild scene astern:

The great naturalist Darwin (wrote Slocum in Sailing Alone Around the World) looked over this seascape from the deck of the Beagle, and wrote in his journal, ‘any landsman seeing the Milky Way would have nightmares for a week.’ He might have added, ‘or seaman’ as well.

Then there’s Sir Francis Chichester. Both a solo flier in the 1930s and a solo round-the-world sailor in 1966-67, he wrote that the thought of Cape Horn “not only frightened me, but I think it would be fair to say that it terrified me. The accounts of the storms there are, quite simply, terrifying… I told myself for a long time that anyone who tried to round the Horn in a small yacht must be crazy. Of the eight yachts I knew to have attempted it, (this was back in 1966, RS) six had been capsized or somersaulted, before, during, or after the passage…”

Not a picnic. Not like crossing the road.

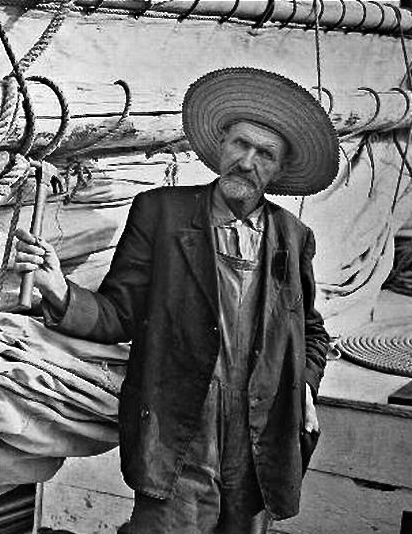

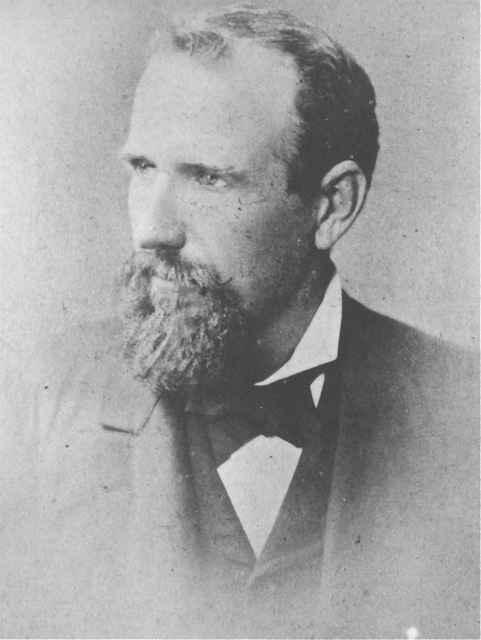

Joshua Slocum, 1844–1909

Just to get our bearings, now that solo circumnavigation has become a record-book contest for teenagers, let’s remember what Captain Joshua Slocum achieved over one hundred years ago. Since that time there have been hundreds of ocean sailors and many narratives, yet both his voyage and his book remain unique. In the introduction to a 1948 edition Arthur Ransome wrote that

Sailing Alone Around the World is one of the immortal books. Joshua Slocum was the first man to sail round the world in a small boat with none but himself as captain, mate and crew. Other men may repeat the feat. No other man can be the first. Captain Slocum’s place in history is as secure as Adam’s.

Captain Joshua Slocum

Briefly told, Slocum was born in Nova Scotia, his formal education ended when he was ten, and after running away from home at the age of 16 he lived almost entirely at sea. Along with boat-building, sailing was his world. Other lives and vocations he explored through the library he carried with him when, as a ship’s master on full-rigged ships, he had room for books. (See Note at end of this essay for the books in his library.) Later in life, on his round-the-world voyage, when he found that in calm weather his boat Spray would keep on its course with the helm lashed, he told how he spent his time. It was not taken up at the wheel:

“No man, I think, could stand or sit and steer a vessel round the world. I did better than that; for I sat and read my books, mended my clothes, or cooked my meals and ate them in peace. I had already found that it was not good to be alone, and so I made companionship with what there was around me, sometimes with the universe and sometimes with my own insignificant self; but my books were always my friends, let fail all else.”

Virginia Slocum

A notable aspect of Slocum’s life at sea is that after being given command of the barque Washington, in 1869, his wife Virginia always travelled with him, bearing several children to whom she taught their lessons as the family sailed along. Husband and wife were close; after Virginia’s early death in Buenos Aires in 1884 he took a long time to get over it. One of his sons wrote that “Father’s days were done with the passing of mother. They were pals…” Another son said that “When she died, father never recovered. He was like a ship with a broken rudder.”

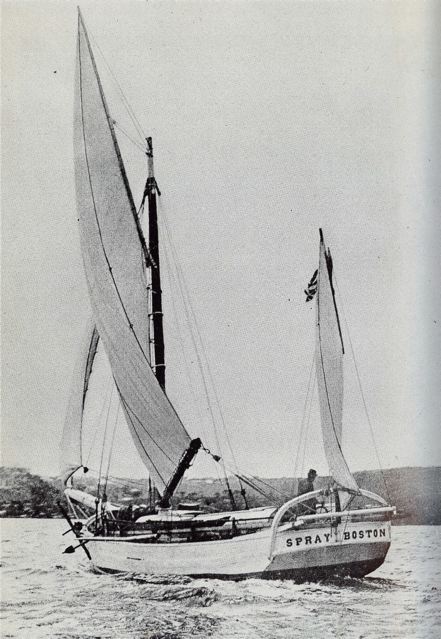

The next decade was one of decline. But ten years later he had recovered enough to make that legendary solo voyage in a fishing smack found near New Bedford. Though the Spray was old, and propped up in a farmer’s field, he decided to rebuild it himself (“My ax felled a stout oak-tree near by for a keel… and the much-esteemed stem-piece was from the butt of the smartest kind of pasture oak.”). Then, aged 52, he set off alone to circumnavigate the globe — with no engine, no generator, no electricity, no self-steering mechanism or autopilot, no radio, no refrigerator, no GPS, no roller-furling sails, no sponsors, and a $1.50 tin clock for a chronometer. It is said he departed with only $1.80 in cash; though he profitably traded miscellaneous goods along the way.

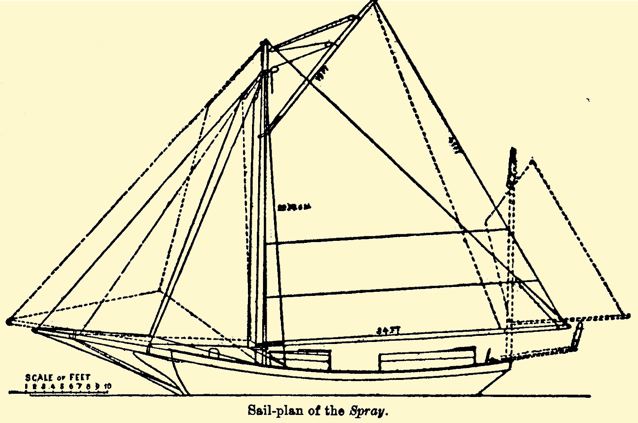

Sail Plan, Spray

While most sailors now go west to east, taking advantage of the prevailing winds, Joshua Slocum sailed east to west — the hard way round Cape Horn. How was his prodigious circumnavigation achieved? As Richard Henderson writes in Singlehanded Sailing, “The success of his voyage was largely due to masterful seamanship. He learned to read the weather, maneuver his clumsy craft in tight places, handle her heavy gear, claw to windward when necessary, ride to a sea anchor, lie to or run off in heavy weather, and balance his boat so that she would sail for days with the helm unattended.” And, we might add, by being alert to danger every minute he was afloat.

Not asleep or dreaming.

Jessica and Jesse: Living the Dream

Whether Jessica Watson was awake, asleep, or just dreaming when her boat Ella’s Pink Lady collided with a container ship just before she set off round the world is unclear. It happened at night, and there are claims and counter-claims. But the romantic rhetoric of dreaming is everywhere in the writings of modern teenage record-breakers. At her website there’s “a big thanks to our sponsors for making Jessica’s dream come true.” Elsewhere she “hopes to inspire everyone with a dream in their heart”, a sentiment fervently endorsed by her fans: “Go Jessica, live the dream!” they cry again and again.

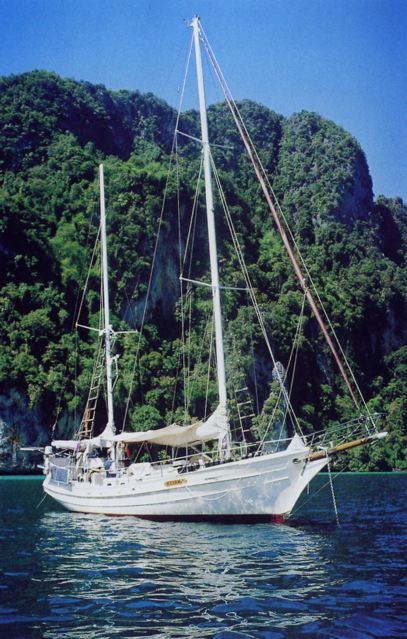

Ella’s Pink Lady leaves Sydney

She also acknowledges the inspiration of Jesse Martin, the young Australian who rounded the world in 1999 – 2000, and whose record at age 17 she hopes to shatter. Martin may be a somewhat indifferent sailor, but you can’t take away from him the fact that he set out, broke the age record sailing an identical S & S 34 to Jessica’s, and wrote a book about it. It must be said here and now, however, that one record of Martin’s is unlikely to be broken for many years. His writings contain more windy nonsense about ‘dreaming’ and ‘living the dream’ than all history has recorded hitherto. Even a well-known American dreamer gets into the act on a prefatory page:

“I encourage you to continue to set high goals for yourself and to continue to pursue your dreams. You can do anything that your imagination, effort, and talent will let you achieve. Best wishes. Sincerely, Bill Clinton.”

With Jesse and Jessica we reach the end of the road pioneered by Joshua Slocum. Teenage circumnavigations are now increasingly Showbiz — part of the theatrical-histrionic-industrial complex (aka the media). How far this will be true of Jessica’s trip remains to be seen. But with Jesse Martin’s 2002 world-wide adventure cruise on the schooner Kijana, the spin-off from his circumnavigation, it was made fully explicit. For this project the globe was seen as a vast movie set, a sequence of colorful painted backgrounds where a cast of characters — some amateur and some professional — were supposed to enact defined and scripted “adventures”, the “natives” changing from place to place but really being just exotic décor.

Unpacking the word “Showbiz” may help us see what has happened. Looking back a hundred years to Slocum, you see a tough and secure identity doing something no other man had done. Solo round-the-world sailing began with a resourceful, self-sufficient, hardworking and humorous New Englander, not Leonardo DiCaprio. Taking things semantically, first Captain Joshua Slocum did the “business”; then through writing and lecturing he put himself and his remarkable achievement on “show”. With Jesse and Jessica this order is reversed. First, negotiations are carried out with all sorts of sponsors who know exactly what sort of “show” they require. Then Jesse and Jessica go out to do the “business” — if they can. This is called reality television.

Kijana, Schooner

Sailing solo around the world made Jesse Martin a celebrity. But what to do next? How about a bigger dream, with a huge white photogenic schooner, media deals, and an American publisher talking up another book, most of it directly inspired by Showbiz itself — a movie in fact. In his account of this ill-fated project in Kijana, the Real Story, (Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 2005, Kijana being the name of the boat) Jesse’s mission statement tells how the new voyage will be a three-year-long “adventure” with “tropical jungles, exotic ports, sparse deserts and wild natives”. After leaving Australia he’d head “straight for Papua New Guinea; then on to Indonesia, India and Africa, where the crew would leave the boat on the coast of Tanzania and cross the continent by land while another crew would sail our boat around to meet us on the other side. I wanted to ride camels across the Serengeti Plain, then raft down the Congo River to meet the boat on the Atlantic coast.” (Kijana, the Real Story, 12-13)

The Amazon, the Caribbean, and the Galapagos Islands would follow, in a thirteen-part series with corporate backing pitched at the youth market. And before long everything fell into place. In 2002, with his best friend and his brother on a $285,000 boat christened Kijana, plus two young women chosen for their looks and their music, Jesse sailed off “to find and film paradise” — first making for Maya Bay in Thailand. Maya Bay was “one of the places I dreamed of visiting, and the location of the Leonardo DiCaprio film The Beach”, a movie that “portrayed the image of paradise we were searching for.” It may have been inspiring at the time, but as a film The Beach lies somewhere between a ClubBohème wet dream and a vision of hippie apocalypse, where an exclusive group of swinging singles find “paradise” on an unmarked island in the Gulf of Thailand — until bullets start flying.

The Amazon, the Caribbean, and the Galapagos Islands would follow, in a thirteen-part series with corporate backing pitched at the youth market. And before long everything fell into place. In 2002, with his best friend and his brother on a $285,000 boat christened Kijana, plus two young women chosen for their looks and their music, Jesse sailed off “to find and film paradise” — first making for Maya Bay in Thailand. Maya Bay was “one of the places I dreamed of visiting, and the location of the Leonardo DiCaprio film The Beach”, a movie that “portrayed the image of paradise we were searching for.” It may have been inspiring at the time, but as a film The Beach lies somewhere between a ClubBohème wet dream and a vision of hippie apocalypse, where an exclusive group of swinging singles find “paradise” on an unmarked island in the Gulf of Thailand — until bullets start flying.

What on earth can one say? First, Jesse’s paradise is a collage of tropical getaway brochures, distant echoes of old South Sea adventure stories, plus Leonard DeCaprio and Virginie Ledoyen making out under the palms. That’s for starters. Muddled into the dream is an anthropological fantasy that tribal peoples who live in Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and the Pacific, not to mention Africa and South America too, are waiting in their native simplicity to cater to western bohofolk in big yachts with nothing better to do.

It’s unresistingly puerile — but that itself raises serious questions. Is it also a vision shared more generally Downunder? Considering the youthful author’s loosely bohemian background it would be foolish to expect much in the way of historical or cultural understanding. But If you took a surgical slice of his brain might it represent a cross-section of ‘enlightened’ Australian middle-class attitudes as a whole? I suspect it would. And that it reflects widespread regional delusions.

The Antipodal Mind

The attitude toward danger we find in Jessica Watson’s bold yachting venture is suggestive. East of the Indian Ocean, south of Indonesia, and washing indistinctly out into the Pacific, something appears to have gone missing from the Darwinian survival kit. Both in Australia and New Zealand — traditionally known as the “Antipodes” — there’s a feeling that while nasty things happen in the rest of the world, they’ll never happen here to us. The Antipodal Mind assumes that because we’re sincerely multicultural and opposed to war and have busy academic Peace Centers busily doing whatever Peace Centers do — we’ll be safe.

Prompted by the tourist industry, there has also been a sentimental tendency to glamorise people, places and activities once thought unglamorous and risky to visit. From the security of the Antipodes unstable Pacific micro-states are regularly shown as a benign mixture of palms, lagoons, and adorable brown children with beguiling eyes, places where handsome yachts and giant cruise ships lie peacefully at anchor.

Under the rubric of romantic primitivism large numbers of antipodal bien-pensants convinced themselves that even the most violent tribal societies were rather fun — and were certainly colorful and exciting. Disneyfication added another element. Where primitivist fantasy denies there is anything to fear from tribalism, romantic puerility presents us with the intellectual and educational understanding of a child. It’s as if everything the West has painfully learnt about the Third World in the last fifty years has been ignored, occluded, or erased. Is it because of this lethal mix of sentimentalism, incuriosity, and raw ignorance that tourists go year after year to places where there’s a reasonable chance of being blown to bits?

What do outsiders make of it? I think it can be confidently said that you won’t find these delusions in the lands northwest of here, where most Asians see such attitudes as a mental affliction of farang. Living amongst upheavals and riots, floods and famines, political corruption and political despotism, desperately crowded cities and civil wars that have decimated whole populations, Asians matter-of-factly know danger for what it is (part of daily life), and are inclined to regard those who by a freak of geography have been shielded from such things as fools in a fool’s paradise. Like birds on Pacific Islands that have no predators — rather like New Zealand kiwis indeed — their sense of self-preservation seems underdeveloped. Cape Horn? Not to worry. Like crossing the street.

But let’s cut to the chase: only people living at the end of the earth, safely surrounded by deep water, get to think about danger this way. And from this perspective that comment on the negligible dangers of Cape Horn is a characteristic expression of the Antipodal Mind. It complacently assumes that the GPS will function flawlessly; that navigation will need neither sextant nor log tables; that weather forecasts will reliably get through; and that the vulnerable vane/oar/linkages of the self-steering gear at the stern will never be swept away. Plus of course that a secure radio link will enable encouraging daily conversations between Team Watson and Jessica, providing an invisible supportive web of world-wide contacts that give “solo sailing” a rather different meaning than it used to have. No problemo. No danger. Just a breeze.

Worse things do happen at sea

Yet even a casual landlubberly inquiry shows malfunctions and mishaps all the time. True, September’s UK Yachting Monthly starts with the usual ingratiating images of yachts in palm-fringed lagoons, but the very next page has lightning melting a VHF aerial on a mast. That means the end of radio contact: not good. Nearby a Bronze Medal is being awarded to a Scottish lifeboat man. He had rescued two Swedes from a boat that had been knocked down twice in a Force 9 gale with 20-foot waves — and the rescue depended entirely on the radio working as it should. Elsewhere there’s a woman climbing out of a yacht wrecked in Mexico. Somehow the autopilot had spontaneously gone from ‘auto’ to ‘standby’; because there was no power no warning sounded; disaster swiftly followed.

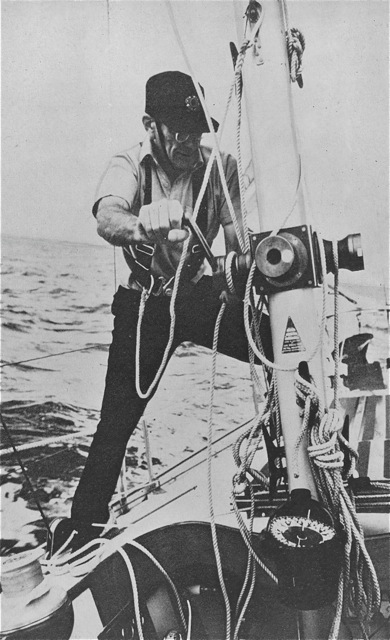

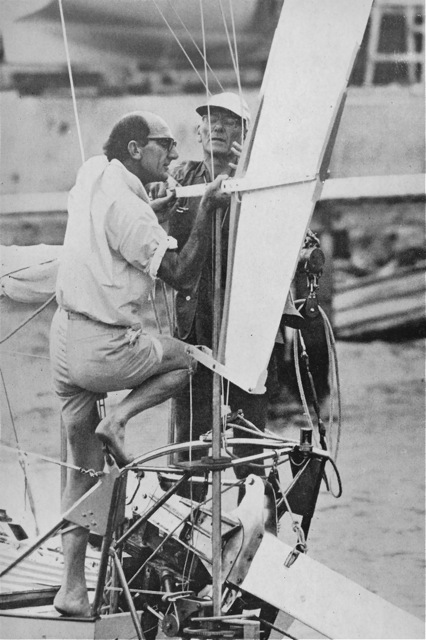

Sir Francis Chichester at work

Sir Francis Chichester’s Gipsy Moth Circles the World is full of this sort of thing. The book seems at times one long grumble, a catalog of mishaps and an exhausting litany of complaint. One day some broken glass cut the man’s bare feet and made him cross. But what did he expect, from an unsecured bottle of whiskey, except shattered fragments everywhere when the boat turned upside-down in the Tasman Sea? The pervasive tone of exasperation makes Gipsy Moth Circles the World a hard read compared to Joshua Slocum’s good-humored and humorous Sailing Alone Around the World (1898). All the same, the picky relentlessness of Chichester’s detail shows clearly what young sailors like Jessica, with more modern gear and more stable boats, still have to face.

If he isn’t fixing a valve in the motor’s exhaust that is letting in water, he’s trying to get an electric bilge pump working or secure a slipping self-steering vane. When he isn’t fixing the brake on the propeller, he’ll be spending a whole morning bleeding the engine’s fuel system, fuel pump, priming pump, and filter. There are so many things to do that he provides readers with the maintenance list he made out, 71 items long, as an agenda. These are the first ten tasks it contains:

Check water tank connections

Secure cockpit locker hasp

Fix preventer to galley drawers

Try self-steering vane without extra lead

Freshen nip of tiller lines to self-steering

Check engine water level

Stow burgee stick

Rig tiller tackle to cabin

Try more slack on self-steering oar

More solid cockpit repair to keep deck water out

Chichester fixing self-steering gear

The other day Jessica reported using goo to fix persistent deck or cockpit leaks. Then on Nov 9th she said she was doing some jobs she’d put off because of “bouncy” seas, and was working on her own maintenance list, including “a really good check over for chafe and wear.” On November 16th she gave “the little Yanmar engine a full polish up and scrubbed out the bilges.” There seems to be a notion among teenagers that polishing an engine makes it run better. Jesse Martin also describes cleaning the outside of an engine, giving it a pat, and being pleased by the way it subsequently performed. This is evidently considered maintenance. But Jessica’s daily blog is endearing, with plenty about dolphins, while baking cupcakes was a huge turn-on for the fans.

“Wow!!!!! Love those cupcakes…” wrote Rob of Ingleburn, “You are truly an inspiration to everyone. Keep doing what you are doing. You are wonderful.”

Captain Joshua Slocum also cooked at sea. Feeling in need of fortification after Cape Horn he fried some buns. As sturdy in their construction as the Spray itself, one of them still sat on the mantel of his home back in Massachusetts some years later. So perhaps the two matelots have an unexpected affinity. Anyway Jessica’s okay. There’s a lot of what is best in the Antipodal character about her — ‘let’s give it a go’ combined with a jaunty attitude and an optimistic will to succeed. We wish her well. Luckily the middle of the ocean has been serene so far and the Pacific well-behaved — almost a danger-free zone. Slocum once knew a ship’s master who took a benignly complacent view of the Pacific Ocean and claimed that its perils had been much exaggerated. Then a hurricane nearly blew his ship out of the water. After that, wrote Slocum, he was a changed man. Maybe that will happen to Jessica too. Maybe not. We shall see.

Congratulations Jessica! Well done and welcome home — Sydney May 15 2010.

Sailing Alone Around the World

By Joshua Slocum

Chapter One

A blue-nose ancestry with Yankee proclivities – Youthful fondness for the sea – Master of the ship Northern Light – Loss of the Aquidneck – Return home from Brazil in the canoe Liberdade – The gift of a “ship” – The rebuilding of the Spray – Conundrums in regard to finance and calking – The launching of the Spray.

In the fair land of Nova Scotia, a maritime province, there is a ridge called North Mountain, overlooking the Bay of Fundy on one side and the fertile Annapolis valley on the other. On the northern slope of the range grows the hardy spruce-tree, well adapted for ship-timbers, of which many vessels of all classes have been built. The people of this coast, hardy, robust, and strong, are disposed to compete in the world’s commerce, and it is nothing against the master mariner if the birth-place mentioned on his certificate be Nova Scotia. I was born in a cold spot, on coldest North Mountain, on a cold February 20, though I am a citizen of the United States — a naturalized Yankee, if it may be said that Nova Scotians are not Yankees in the truest sense of the word.

Joshua Slocum aged about 39

On both sides my family were sailors; and if any Slocum should be found not seafaring, he will show at least an inclination to whittle models of boats and contemplate voyages. My father was the sort of man who, if wrecked on a desolate island, would find his way home, if he had a jack-knife and could find a tree. He was a good judge of a boat, but the old clay farm which some calamity made his was an anchor to him. He was not afraid of a capful of wind, and he never took a back seat at a camp-meeting or a good, old-fashioned revival.

As for myself, the wonderful sea charmed me from the first. At the age of eight I had already been afloat along with other boys on the bay, with chances greatly in favor of being drowned. When a lad I filled the important post of cook on a fishing-schooner; but I was not long in the galley, for the crew mutinied at the appearance of my first duff, and “chucked me out” before I had a chance to shine as a culinary artist. The next step toward the goal of happiness found me before the mast in a full-rigged ship bound on a foreign voyage. Thus I came “over the bows,” and not in through the cabin windows, to the command of a ship.

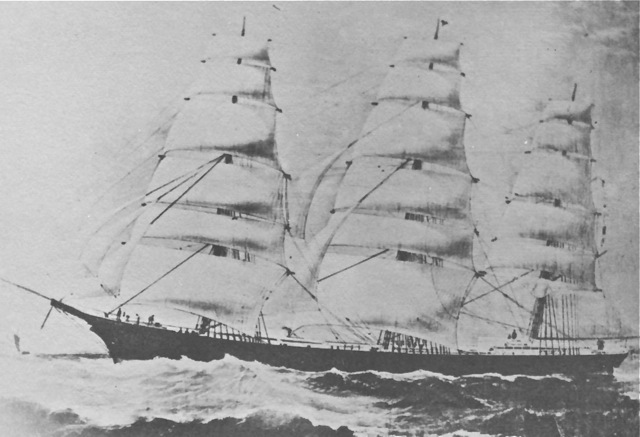

The Northern Light

My best command was that of the magnificent ship Northern Light, of which I was part-owner. I had a right to be proud of her, for at that time — in the eighties — she was the finest American sailing-vessel afloat. Afterward I owned and sailed the Aquidneck, a little bark which of all man’s handiwork seemed to me the nearest to perfection of beauty, and which in speed, when the wind blew, asked no favors of steamers. I had been nearly twenty years a shipmaster when I quit her deck on the coast of Brazil, where she was wrecked. My home voyage to New York with my family was made in the canoe Liberdade, without accident.

My voyages were all foreign. I sailed as freighter and trader principally to China, Australia, and Japan, and among the Spice Islands. Mine was not the sort of life to make one long to coil up one’s ropes on land, the customs and ways of which I had finally almost forgotten. And so when times for freighters got bad, as at last they did, and I tried to quit the sea, what was there for an old sailor to do? I was born in the breezes, and I had studied the sea as perhaps few men have studied it, neglecting all else.

Next in attractiveness, after seafaring, came ship-building. I longed to be master in both professions, and in a small way, in time, I accomplished my desire. From the decks of stout ships in the worst gales I had made calculations as to the size and sort of ship safest for all weather and all seas. Thus the voyage which I am now to narrate was a natural outcome not only of my love of adventure, but of my lifelong experience.

* * *

One midwinter day of 1892, in Boston, where I had been cast up from the old ocean, so to speak, a year or two before, I was cogitating whether I should apply for a command, and again eat my bread and butter on the sea, or go to work at the shipyard, when I met an old acquaintance, a whaling-captain, who said: “Come to Fairhaven and I’ll give you a ship. But,” he added, “she wants some repairs.”

The captain’s terms, when fully explained, were more than satisfactory to me. They included all the assistance I would require to fit the craft for sea. I was only too glad to accept, for I had already found that I could not obtain work in the shipyard without first paying fifty dollars to a society, and as for a ship to command — there were not enough ships to go round. Nearly all our tall vessels had been cut down for coal-barges, and were being ignominiously towed by the nose from port to port, while many worthy captains addressed themselves to Sailor’s Snug Harbor.

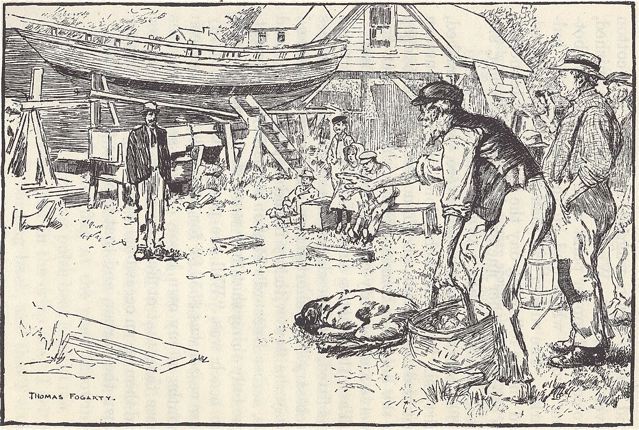

The next day I landed at Fairhaven, opposite New Bedford, and found that my friend had something of a joke on me. For seven years the joke had been on him. The “ship” proved to be a very antiquated sloop called the Spray, which the neighbours declared had been built in the year 1. She was affectionately propped up in a field, some distance from salt water, and was covered with canvas.

The people of Fairhaven, I hardly need say, are thrifty and observant. For seven years they had asked, “I wonder what Captain Eben Pierce is going to do with the old Spray?” The day I appeared there was a buzz at the gossip exchange: at last some one had come and was actually at work on the old Spray. “Breaking her up, I s’pose?” “No; going to rebuild her.” Great was the amazement. “Will it pay?” was the question which for a year or more I answered by declaring that I would make it pay.

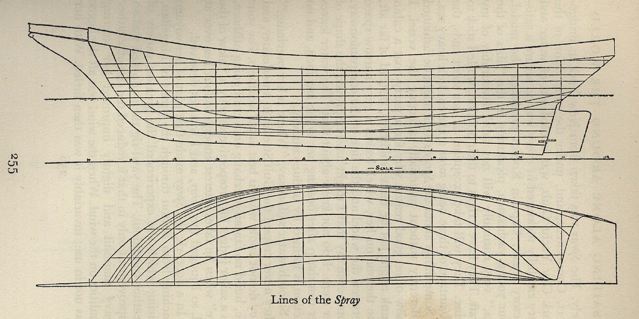

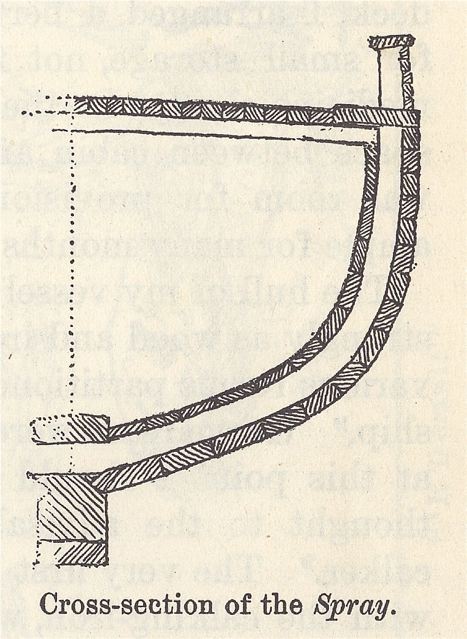

Lines of Spray

My ax felled a stout oak-tree near by for a keel, and Farmer Howard, for a small sum of money, hauled in this and enough timbers for the frame of the new vessel. I rigged a steam-box and a pot for a boiler. The timbers for ribs, being straight saplings, were dressed and steamed till supple, and then bent over a log, where they were secured till set. Something tangible appeared every day to show for my labor, and the neighbours made the work sociable.

It was a great day in the Spray shipyard when her new stem was set up and fastened to the new keel. Whaling-captains came from far to survey it. With one voice they pronounced it “A1”, and in their opinion “fit to smash ice.” The oldest captain shook my hand warmly when the breast-hooks were put in, declaring that he could see no reason why the Spray should not “cut in bow-head” yet off the coast of Greenland.

The much-esteemed stem-piece was from the butt of the smartest kind of a pasture oak. It afterward split a coral patch in two at the Keeling Islands, and did not receive a blemish. Better timber for a ship than pasture white oak never grew. The breast-hooks, as well as all the ribs, were of this wood, and were steamed and bent into shape as required. It was hard upon March when I began to work in earnest; the weather was cold; still, there were plenty of inspectors to back me with advice. When a whaling-captain hove in sight I just rested on my adz awhile and “gammed” with him.

New Bedford, the home of whaling-captains, is connected with Fairhaven by a bridge, and the walking is good. They never “worked along up” to the shipyard too often for me. It was the charming tales about arctic whaling that inspired me to put a double set of breast-hooks in the Spray, that she might shunt ice.

* * *

The seasons came quickly while I worked. Hardly were the ribs of the sloop up before apple-trees were in bloom. Then the daisies and the cherries came soon after. Close by the place where the old Spray had now dissolved rested the ashes of John Cook, a revered Pilgrim father. So the new Spray rose from hallowed ground. From the deck of the new craft I could put out my hand and pick cherries that grew over the little grave. The planks for the new vessel, which I soon came to put on, were of Georgia pine an inch and a half thick.

The operation of putting them on was tedious, but, when on, the calking was easy. The outward edges stood slightly open to receive the calking, but the inner edges were so close that I could not see daylight between them. All the butts were fastened by through bolts, with screw-nuts tightening them to the timbers, so that there would be no complaint from them. Many bolts with screw-nuts were used in other parts of the construction, in all about a thousand. It was my purpose to make my vessel stout and strong.

Now, it is a law in Lloyd’s that the Jane repaired all out of the old until she is entirely new is still the Jane. The Spray changed her being so gradually that it was hard to say at what point the old died or the new took birth, and it was no matter. The bulwarks I built up of white-oak stanchions fourteen inches high, and covered with seven-eighth-inch white pine. These stanchions, mortised through a two-inch covering board, I calked with thin cedar wedges. They have remained perfectly tight ever since.

Now, it is a law in Lloyd’s that the Jane repaired all out of the old until she is entirely new is still the Jane. The Spray changed her being so gradually that it was hard to say at what point the old died or the new took birth, and it was no matter. The bulwarks I built up of white-oak stanchions fourteen inches high, and covered with seven-eighth-inch white pine. These stanchions, mortised through a two-inch covering board, I calked with thin cedar wedges. They have remained perfectly tight ever since.

The deck I made of one-and-a-half-inch by three-inch white pine spiked to beams, six by six inches, of yellow or Georgia pine, placed three feet apart. The deck-inclosures were one over the aperture of the main hatch, six feet by six, for a cooking-galley, and a trunk farther aft, about ten feet by twelve, for a cabin. Both of these rose about three feet above the deck, and were sunk sufficiently into the hold to afford head-room. In the spaces along the sides of the cabin, under the deck, I arranged a berth to sleep in, and shelves for small storage, not forgetting a place for the medicine-chest. In the midship hold, that is, the space between cabin and galley, under the deck, was room for provision of water, salt beef, etc., ample for many months.

The hull of my vessel being now put together as strongly as wood and iron could make her, and the various rooms partitioned off, I set about “calking ship.” Grave fears were entertained by some that at this point I should fail. I myself gave some thought to the advisability of a “professional calker.” The very first blow I struck on the cotton with the calking iron, which I thought was right, many others thought was wrong. “It’ll crawl!” cried a man from Marion, passing with a basket of clams on his back. “It’ll crawl!” cried another from West Island, when he saw me driving cotton into the seams.

“It’ll crawl!”

Bruno simply wagged his tail. Even Mr. Ben J——, a noted authority on whaling-ships, whose mind, however, was said to totter, asked rather confidently if I did not think “it would crawl.” “How fast will it crawl?” cried my old captain friend, who had been towed by many a lively sperm-whale. “Tell us how fast,” cried he, “that we may get into port in time.” However, I drove a thread of oakum on top of the cotton, as from the first I intended to do. And Bruno again wagged his tail. The cotton never “crawled.”

When the calking was finished, two coats of copper paint were slapped on the bottom, two of white lead on the topsides and bulwarks. The rudder was then shipped and painted, and on the following day the Spray was launched. As she rode at her ancient, rust-eaten anchor, she sat on the water like a swan.

The Spray’s dimensions were, when finished, thirty-six feet nine inches long, over all, fourteen feet two inches wide, and four feet two inches deep in the hold, her tonnage being nine tons net and twelve and seventy-one hundredths tons gross. Then the mast, a smart New Hampshire spruce, was fitted, and likewise all the small appurtenances necessary for a short cruise. Sails were bent, and away she flew with my friend Captain Pierce and me, across Buzzard’s Bay on a trial-trip — all right.

The only thing that now worried my friends along the beach was “Will she pay?” The cost of my new vessel was $553.62 for materials, and thirteen months of my own labor. I was several months more than that at Fairhaven, for I got work now and then on an occasional whale-ship fitting farther down the harbor, and that kept me the overtime.

Note: The strength of Slocum’s prose speaks for itself. It needs no critical gloss. Nonetheless it is of interest that Van Wyck Brooks called Sailing Alone Around the World a “nautical equivalent” of Thoreau’s Walden. Brooks edited an anthology of classic New England literature in 1962, A New England Reader. He included the Strait of Magellan chapters from Sailing Alone Around the World alongside Longfellow, Emerson, Hawthorne, Thoreau, Dana, and Prescott.

It may also be of interest to list some of the books Joshua Slocum took with him to read at sea:

Darwin’s The Descent of Man and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Newcomb’s Popular Astronomy, Todd’s Total Eclipses of the Sun, Bates’s The Naturalist on the Amazons, Macaulay’s History of England, Trevelyan’s Life of Macaulay, Washington Irving’s Life of Columbus, Boswell’s Johnson, Don Quixote, Life on the Mississippi, one or more titles by Robert Louis Stevenson, a set of Shakespeare, and in ‘the poet’s corner’, as he called it, works of Lamb, Moore, Burns, Tennyson, and Longfellow. (Above information courtesy of the works of Walter Magnes Teller.)

An Australian writer living in Sydney, Roger Sandall is the author of The Culture Cult (2001), a study of romantic primitivism and its effects. His work has appeared in a number of places including Commentary, The American Interest, Encounter, The New Criterion, The American, Sight and Sound, Quadrant, Art International, The New Lugano Review, The Salisbury Review, Merkur, Mankind, Visual Anthropology, and Social Science and Modern Society.

An Australian writer living in Sydney, Roger Sandall is the author of The Culture Cult (2001), a study of romantic primitivism and its effects. His work has appeared in a number of places including Commentary, The American Interest, Encounter, The New Criterion, The American, Sight and Sound, Quadrant, Art International, The New Lugano Review, The Salisbury Review, Merkur, Mankind, Visual Anthropology, and Social Science and Modern Society.