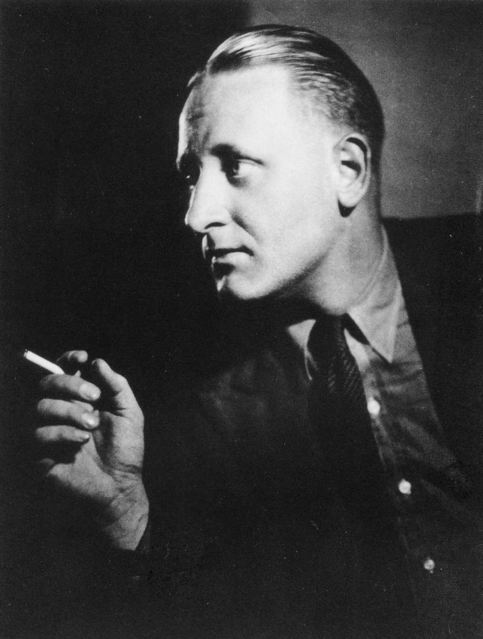

Mr Gunther and Mr Duranty

[This article first appeared in the Autumn 2007 issue of The American Interest with the title “Over There, Then: John Gunther’s Inside Europe”]

The War had started and Churchill had lots on his mind. But even in September 1939 he still had time for John Gunther. The much-travelled American journalist was one of the few outsiders who had been in Moscow on August 24th, the very day the Nazi-Soviet pact was announced, and Churchill wanted to hear how this stunning maneuver was received on Moscow’s streets.

What exactly Gunther told Churchill is unrecorded, but the words of the British leader were something Gunther remembered for years. “Russia,” Churchill murmured, brooding aloud about the Soviet Union, and rehearsing lines that would become famous in a more polished form, “was a mystery in a mystery in a mystery.”

* * *

The wartime meeting with Churchill was no fluke. During the 1930s and 1940s John Gunther’s Inside Europe had made him the most famous American newsman of them all. A friend of both Franklin D. Roosevelt and Dwight Eisenhower, Gunther threw parties at his home in New York for the likes of John Steinbeck, Salvador Dali, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor—Inside Russia was dedicated to his good friend Greta Garbo.

The wartime meeting with Churchill was no fluke. During the 1930s and 1940s John Gunther’s Inside Europe had made him the most famous American newsman of them all. A friend of both Franklin D. Roosevelt and Dwight Eisenhower, Gunther threw parties at his home in New York for the likes of John Steinbeck, Salvador Dali, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor—Inside Russia was dedicated to his good friend Greta Garbo.

He spent perhaps more time than was sensible with Walter Winchell and Elsa Maxwell in places like the Stork Club and Toots Shor’s and 21. But his books anatomising different continents—Inside Latin America, Inside Asia, Inside Africa, Inside Russia—were translated into ninety languages and sold millions of copies around the world.

Yet nothing else was as successful as his 1936 Inside Europe. It foreshadowed what the Nazis had in store. Much as Robert D. Kaplan today has been a Cassandra warning of the descent of entire Third World regions into anarchy, Gunther warned of the European forces leading inexorably to World War II.

Inside Europe

Inside Europe wasn’t a paperback. At the cheaper end of the British market in the 1930s books were selling for sixpence, but this was a whopping 500-page hardback retailing at 30 shillings, or sixty times that price.

That didn’t slow sales one bit. In its first year, 1936, Inside Europe sold 65,000 copies at about 1,000 copies a week, and continued to sell through 1937 at the same rate. By 1939 it had sold nearly 120,000 copies and continued to turn over through the Second World War. John Gunther was later told he was the best-selling American author of non-fiction in Britain since Mark Twain.

There were three reasons for this success, and the first was timing. Appearing first in January 1936 in London published by Hamish Hamilton, and later by Harper’s in the USA, Inside Europe provided a close literary echo, scene by scene and act by fateful act, of the international drama of the times. Running steadily through numerous updated impressions and editions, it climaxed in the “Peace Edition” of October 1938—the month when German troops marched into Czechoslovakia.

In the words of historian John Lukacs “1938 was Hitler’s year”. It saw the annexation of Austria, Neville Chamberlain’s capitulation at Munich, and the occupation of Czechoslovakia. Readers of Inside Europe’s October 1938 edition were able to follow these developments almost as they happened.

Not only were they given brilliant thumb-nail sketches of the Nazis in Germany (and a matchless photograph of Goering at a reception, an enormous bull draped with braid and medals confronting a frail and exquisite lady from Japan) but there were also incisive studies of the whole tragi-comic gallery in Austria, in Czechoslovakia, in France, in Spain, in Italy, in the Balkans, in East Europe. Gunther also dealt ably with the United Kingdom itself, where, through May 1940, the struggle between Churchill and his domestic opponents had yet to play out.

Not only were they given brilliant thumb-nail sketches of the Nazis in Germany (and a matchless photograph of Goering at a reception, an enormous bull draped with braid and medals confronting a frail and exquisite lady from Japan) but there were also incisive studies of the whole tragi-comic gallery in Austria, in Czechoslovakia, in France, in Spain, in Italy, in the Balkans, in East Europe. Gunther also dealt ably with the United Kingdom itself, where, through May 1940, the struggle between Churchill and his domestic opponents had yet to play out.

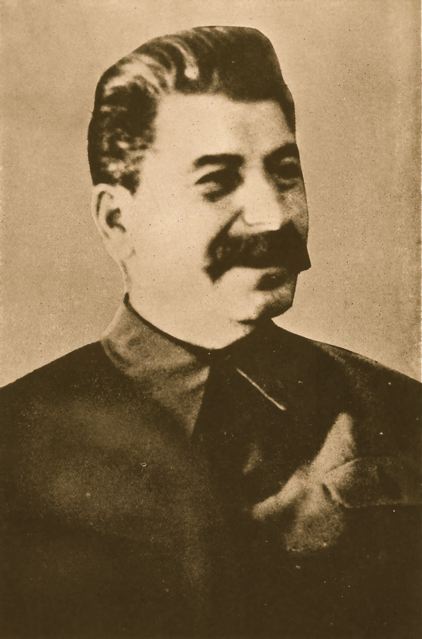

As a portrait gallery the photographs are outstanding—with one striking exception. The shot of Stalin is a typical blurry Soviet retouch job, where the crude hand of some studio helot can be seen brushing the hair, brightening the eyes, and putting a smile on the despot’s face. All too lamentably, this pictorial failing also extends to the text in the last chapters about Stalin and the USSR—something we shall come to in due course.

The second reason for the book’s success was depth. Though Gunther’s later work was often based on visits of only days or weeks, Inside Europe drew on twelve years’ research and reporting from every European capital; on personally investigating Hitler’s Austrian background and personally witnessing events like the Reichstag fire trial; on continually sharing information with journalistic colleagues Dorothy Thompson, Vincent Sheean, H. R. Knickerbocker and William Shirer, and with literary acquaintances Sinclair Lewis and Rebecca West.

The high cost of Nazi hoodlums

The third reason for the book’s success was its style and tone. Gunther grew up in Chicago, cut his journalistic teeth at the Chicago Daily News before going to Europe, and enjoyed colorful muckraking journalism. During a trip back to the Chicago at the end of the 1920s he collaborated on a News article titled “The High Cost of Hoodlums” that appeared in the October 1929 issue of Harper’s Magazine. It told how you could have an enemy “bumped off” for as little as $50, though the rate for a newspaper man like himself might be as high a $1000. In Inside: the Biography of John Gunther (1992) Ken Cuthbertson wrote that:

Despite the fact that “The High Cost of Hoodlums” was written sixty years ago, it retains its vitality as a superb historical snapshot of the Chicago of 1929… It provided a highly readable behind-the-scenes look at how 600 hoodlums had succeeded in terrorizing Chicago’s three million citizens.

One way of looking at Inside Europe is to see it as “a highly readable behind-the-scenes look” about the even larger number of hoodlums who were already terrorizing Germany and would soon menace the continent. BBC producer Brian Miller described in 2001 how the “racy mixture of politics and Capitol Hill gossip” put together by Drew Pearson and Robert Allen in 1931, Washington Merry Go Round, successfully pioneered muckraking book journalism in the US.

Cass Canfield, president of Harper & Brothers in New York, thought the same approach might be tried on Europe’s dictators. He chose Gunther to write the book, and Gunther’s powerful style ensured that Inside Europe broke through the suffocating climate of active censorship and intimidation (“this fog of untruth, or else of censorship, which was really a kind of self-censorship”) that was depriving British readers of the facts about Hitler and the drift to war.

In Vienna since 1930, Gunther had several things going for him. First, he was fast and could meet deadlines. Second, according to Brian Miller, “he was not subject to conservative proprietorial censorship because both his publishers were liberally minded and inclined to let him write whatever he liked, provided it ‘took the lid off’ something.” Third, “he was not subject to censorship and intimidation by dictators themselves because he made quick raids into their territories and only wrote when safely back in England or the USA.”

Inside Europe was a huge commercial success that sold half a million copies and gave him political entrée everywhere. Not only Churchill welcomed him. Two years later in 1941 in Washington, after returning from Latin America, Sumner Welles called Gunther in to brief Roosevelt on the region. Welles had provided letters of introduction to a dozen national leaders, and now Gunther was supposed to report what he’d found: Hitler had boasted of building “a new Germany” in Brazil, and Nazi sympathizers were everywhere.

But Roosevelt appeared less receptive than Churchill, and Gunther hardly got a word in. Instead he was treated to a rambling 45-minute lecture on foreign affairs during which, Gunther later wrote, “I kept thinking that FDR looked like a caricature of himself, with the long jaw tilting upward, the V-shaped opening of the mouth when he laughed, the two long deep parentheses that closed the ends of his lips.”

With Walter Duranty in Moscow

When John Gunther headed for Europe in 1924 it was after a two-year spell with the Chicago Daily News working alongside Ben Hecht and Carl Sandburg. In London he met Dorothy Thompson, a strong influence and life-long friend, and had an affair with Rebecca West, nine years his senior, who opened doors for him in British literary circles. In London he also married his first wife Frances—the beginning of a stressful relationship that ended in 1944.

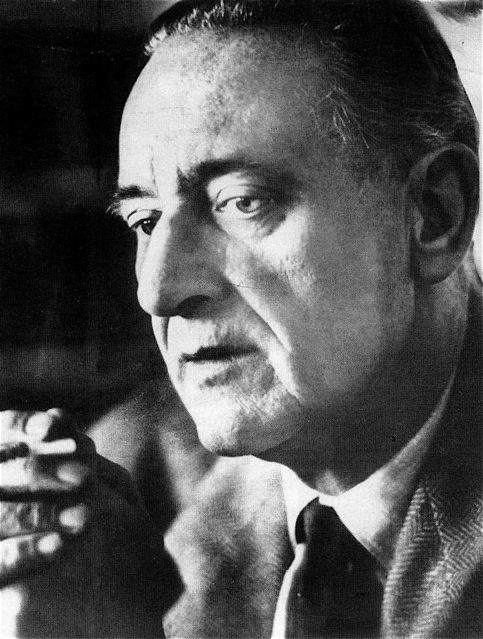

During those years he reported from Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Constantinople, and Moscow. It was in Moscow in 1928 that Gunther first met the New York Times representative Walter Duranty—in those days it seems everybody who went to Moscow did. Visiting Duranty’s apartment he reported,

When one dines with him in Moscow, an extremely pretty girl, smart in semi-evening frock, opens the door, shaking hands. She then disappears again, and late in the evening, asks Walter if he wants to get to work, she has finished the Izvestia proofs. Then they go to bed together. In the morning, she shines the shoes. Mistress, secretary, servant. An unholy trinity for you! Of course, by Moscow law, since they share the same residence, she’s his wife, too…

The pretty girl’s name was Katya, by whom Duranty later had a son. But the mild irregularity of the arrangement Gunther witnessed in Moscow was merely the tip of an iceberg. In Paris in the years before 1914, Duranty was a close friend of Aleister Crowley, a genuine madman fascinated by excretory functions, sexually aroused by blood and torture, and a “master” of the occult.

Duranty and Crowley shared the same woman, Jane Cheron, and all three of them were heavily into opium, sex, and black magic. Even when Duranty was escorting Gunther around Moscow in 1928 he remained in some sort of marital relation with Cheron, who was still in France. Did Gunther know any of this?

Perhaps he did and perhaps he didn’t care. Duranty, who had lost a foot in a railway accident and had a limp (the picture shows him not long after this event) was a famous raconteur and the pleasure of his company seems to have swept all doubts aside. In Stalin’s Apologist (1990) Sally J. Taylor tells how forty years later he and his wife visited Duranty where he was living in Orlando, Florida. Duranty came over to the motel where the Gunthers were staying, and according to Jane Gunther he was “enchanting, in his very best form.” They all stayed up until 4.00am, with Walter being “terribly funny, and very very wicked.” After Duranty left their motel, John turned to his wife and said, “Walter is just a scamp!”

Perhaps he did and perhaps he didn’t care. Duranty, who had lost a foot in a railway accident and had a limp (the picture shows him not long after this event) was a famous raconteur and the pleasure of his company seems to have swept all doubts aside. In Stalin’s Apologist (1990) Sally J. Taylor tells how forty years later he and his wife visited Duranty where he was living in Orlando, Florida. Duranty came over to the motel where the Gunthers were staying, and according to Jane Gunther he was “enchanting, in his very best form.” They all stayed up until 4.00am, with Walter being “terribly funny, and very very wicked.” After Duranty left their motel, John turned to his wife and said, “Walter is just a scamp!”

But Duranty was not, alas, just a scamp. He was also a man many regarded then and now as a scoundrel. Not for nothing did Malcolm Muggeridge call him “the greatest liar of any journalist I have met in fifty years of journalism,” or Joseph Alsop describe him as a “fashionable prostitute”, or Robert Conquest, later, call for every word he ever wrote about the Soviets and collectivization to be challenged again and again.

It’s possible that Duranty was in the pay of the Soviets, though another long-term New York Times correspondent, Harrison Salisbury, who looked into things during his own stay in Moscow, denied that Duranty was ever in the pay of anyone except the New York Times.”

Perhaps. Yet it’s inescapable that his immediate reward for doggedly covering up mass murder in the Ukraine was the indulgence of the regime, the tumultuous applause he received in the Waldorf-Astoria in 1933 for assisting America’s diplomatic recognition of the Soviet Union, and a call from Stalin four weeks after Duranty’s return to Moscow offering the unprecedented privilege of a second interview. Stalin’s words at the time, however accurately or inaccurately rendered by Duranty afterwards, were something he quoted with pride for the rest of his life:

Perhaps. Yet it’s inescapable that his immediate reward for doggedly covering up mass murder in the Ukraine was the indulgence of the regime, the tumultuous applause he received in the Waldorf-Astoria in 1933 for assisting America’s diplomatic recognition of the Soviet Union, and a call from Stalin four weeks after Duranty’s return to Moscow offering the unprecedented privilege of a second interview. Stalin’s words at the time, however accurately or inaccurately rendered by Duranty afterwards, were something he quoted with pride for the rest of his life:

You have done a good job in your reporting the USSR, though you are not a Marxist, because you try to tell the truth about our country and to understand it and to explain it to your readers. I might say that you bet on our horse to win when others thought it had no chance and I am sure you have not lost by it.

The literary culture of the time

All of this raises questions about the journalistic and literary culture of the time. How could someone from the world of Aleister Crowley and the Paris bohemian demi-monde be hired by the New York Times as its resident commentator in Moscow on Russia under Bolshevik rule? How did he become the best-read authority in the US on Stalin’s famous planned economy? Why was such a man invited to Washington in July 1932 to advise Roosevelt about Soviet gold production?

Whatever the answers to those question, it’s plain that Walter Duranty rubbed off on John Gunther. The reason seems to have had something to do with the fact that both Gunther and Duranty were the sort of men who would rather write anything than not write at all. More I suspect than is the case today, many journalists of Gunther’s time were novelists manqué. Only fiction was considered truly prestigious, and readable fiction was not about economic trends, voting patterns, or industrial production. Duranty periodically tried to write both novels and short stories, and in Hollywood, in the years of his decline in the 1940s, he teamed up with Mary Loos, a niece of the screenwriter Anita Loos, to crank out stories and scripts.

The same literary interests drove Gunther. He never stopped writing novels—The Red Pavilion, The Golden Fleece, The Lost City. Most of them sank without trace. Through Rebecca West and Dorothy Thompson he knew dozens of novelists and yearned for literary recognition.

The same literary interests drove Gunther. He never stopped writing novels—The Red Pavilion, The Golden Fleece, The Lost City. Most of them sank without trace. Through Rebecca West and Dorothy Thompson he knew dozens of novelists and yearned for literary recognition.

When success came, however, it was not for fiction but for his reportorial colossus Inside Europe (though he must have enjoyed a Popular Front gathering of the League of American Writers in 1938 when he was invited on stage, and dined with Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald).

When in 1935 Cass Canfield of Harper & Brothers approached him to write Inside Europe, Gunther turned him down—not once but twice. “In those days I was more interested in fiction than in journalism and my dreams were tied up in a long novel about Vienna that I hoped to write.” Only when offered the huge sum of $5000 did Gunther reluctantly accept. What’s interesting is that when he finally sat down to write, the approach was personal and novelistic almost as much as analytic and interpretive. Events in Europe were being shaped by a cast of extraordinary characters, Gunther believed, and Inside Europe would be about their beliefs, motives, and charisma.

To get under way he agreed to produce three articles, and “The three articles”, wrote Gunther, “turned out to be the three chief personality chapters in the book—Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin.” What drove him was the need to show the force of their personalities and how they wielded power over other men. In a letter to Canfield he said that this approach “derives from something deeper in me than political conviction; it comes from the fact, for good or ill, I instinctively think of myself as a novelist.”

* * *

Inside Europe is still riveting. No-one who reads Gunther’s description of Hitler and his friends will easily forget it, whatever they may have read since World War II:

He reads almost nothing. He dislikes intellectuals. He has never been outside Germany since his youth in Austria and speaks no foreign language, except a few words of French. He is nearly oblivious of ordinary personal contacts. A colleague of mine travelled with him, in the same aeroplane, day after day, for two months during the 1932 electoral campaigns. Hitler never talked to a soul, not even to his secretaries, in the long hours in the air; never stirred; never smiled.

Gunther had also spent time in Bucharest and knew the ominous mixture of Ruritanian farce and fascist menace to be found in Rumania. Only two streets away from King Carol’s palace one could see well-dressed members of the Iron Guard lounging in a café, sipping Turkish coffee, and talking about revolution. Founded in 1927 the program of the Iron Guard, he wrote, “was a fanatic, obstreperous sub-Fascism on a strong nationalist and anti-Semitic basis. Its members trooped through the countryside, wore white costumes, carried burning crosses, impressed the ignorant peasantry, aroused the students in the towns.”

The portrayal of Stalin

So far so good. And it’s reasonably good for hundreds of pages. But then one comes to Stalin—and it’s pure undiluted Walter Duranty. Stalin has, we are told

So far so good. And it’s reasonably good for hundreds of pages. But then one comes to Stalin—and it’s pure undiluted Walter Duranty. Stalin has, we are told

“Guts. Durability. Physique. Patience. Tenacity. Concentration. If he has nerves, they are veins in rock. His perseverance, as Walter Duranty says, is ‘inhuman’. When candour suits his purpose, no man can be more candid. He has the courage to admit his errors, something few other dictators dare do. In his article ‘Dizzy from Success’ he was quite frank to admit that the collectivisation of the peasants had progressed too quickly.”

This is truly a gem. Stalin’s magnanimity is shown by his “frankness” in “admitting” that collectivisation had “progressed too quickly.” Gunther sums up the desperate suicidal resistance of the peasants in the following four sentences: “The peasants tried to revolt. The revolt might have brought the Soviet Union down. But it collapsed on the iron will of Stalin. The peasants killed their animals, then they killed themselves.”

Yes. John Gunther actually wrote that it wasn’t Stalin, or the Communist Party, or the NKVD, or the Red Army troops who seized their grain and herded them without food or water onto railway wagons and shot them if they resisted; they “killed themselves.”

Even so, Inside Europe was a major achievement. It brought to public notice the Empire of Evil that was about to expand and take over the whole of central Europe. It powerfully confirmed the Nazi menace Churchill had toiled for years to publicise. And Gunther’s Inside Europe played no small part in bringing US elite opinion out of the dangerous miasma of isolationism that prevailed.

That such a perceptive journalistic observer could be drawn into Duranty’s deceptions about the Soviets had no simple explanation. It may however be because one of Gunther’s strongest personal virtues, loyalty, here became also a vice. He could never bring himself to believe (or to even imagine) that however entertaining Duranty may have been down through the years, and however firmly he had stood by his side during the painfully protracted death of Gunther’s son, his old friend from the 1920s was also a thorough scoundrel whose writings about Stalin were full of lies.

An Australian writer living in Sydney, Roger Sandall is the author of The Culture Cult (2001), a study of romantic primitivism and its effects. His work has appeared in a number of places including Commentary, The American Interest, Encounter, The New Criterion, The American, Sight and Sound, Quadrant, Art International, The New Lugano Review, The Salisbury Review, Merkur, Mankind, Visual Anthropology, and Social Science and Modern Society.

An Australian writer living in Sydney, Roger Sandall is the author of The Culture Cult (2001), a study of romantic primitivism and its effects. His work has appeared in a number of places including Commentary, The American Interest, Encounter, The New Criterion, The American, Sight and Sound, Quadrant, Art International, The New Lugano Review, The Salisbury Review, Merkur, Mankind, Visual Anthropology, and Social Science and Modern Society.