This month a glance at the rural scene—at horses and country life and the mishaps and misadventures inseparable from life on the range and the farm. Starting long ago (and taking a swipe at a neglectful prehistorian along the way) we visit the Parthenon and then Virgil, take in a rodeo in Queensland, and follow this with excerpts from three writers—the great Australian humorist Steele Rudd, an American chronicler of life on the range, J. Frank Dobie, and the New Zealand-born Herbert M. Barker. From which it will appear that the frustrations of inadequate reference books are trivial compared to the frustrations of working with horses and camels.

Prehistorians: a complaint

All I wanted was some information about the first horses and riders, the first roundup and where it all happened—in other words what is called the ‘domestication’ of the horse: it should have been around 6000 or 7000 BC in Central Asia. Simple enough you’d think, and I had a reference work right there on the shelf beside me: After the Ice: a Global Human History 20,000–5000 BC, six hundred pages and over two inches thick.

The word “global” is always reassuring, so imagine my shock when I found nothing whatever about the horse in the index, though a whole list of species from guinea pigs to zebu were carefully listed. How could this be? Author Steven Mithen is Professor of Early Prehistory at Reading University, and the author of The Prehistory of the Mind and other well-regarded books. It is impossible he doesn’t know at least something about the importance of equus caballus to mankind.

But this being England, and the professor being an Englishman, and the university being Reading not Oxford, and the upper classes being inclined to hunting and shooting, there must be a deeper significance. And unless I’m very much mistaken it has to do with social class. In refined circles the troglodytic burrowing activities of prehistorians are infra dig, manifestly identified with the lesser quadrupeds—badgers and moles and such. In contrast, you’d never catch a classical archaeologist of the old school ignoring the horse—the famous pith helmet brigade of Sir Austen Henry Layard of Nineveh, or Howard Carter of Tutankhamen’s tomb, or Sir Arthur Evans of Knossos, or Sir Mortimer Wheeler—they grew up with horses; some of their ponies were best friends.

But this being England, and the professor being an Englishman, and the university being Reading not Oxford, and the upper classes being inclined to hunting and shooting, there must be a deeper significance. And unless I’m very much mistaken it has to do with social class. In refined circles the troglodytic burrowing activities of prehistorians are infra dig, manifestly identified with the lesser quadrupeds—badgers and moles and such. In contrast, you’d never catch a classical archaeologist of the old school ignoring the horse—the famous pith helmet brigade of Sir Austen Henry Layard of Nineveh, or Howard Carter of Tutankhamen’s tomb, or Sir Arthur Evans of Knossos, or Sir Mortimer Wheeler—they grew up with horses; some of their ponies were best friends.

To be honest, when I looked at the text of Mithen’s book and turned the pages, the word ‘horse’ did crop up now and then. He mentions paintings of horses from 25,000 BC at the cave of Pech Merle in France. The extinction of the original native American horse about 10,000 years ago is touched on. In China around 6,800 BC horses are said to have been among the local fauna. Herds of onager or wild ass once roamed in Mesopotamia. And so on. But about the domestication of the horse this reader could find nothing at all. It seemed only too typical that around 7000 BC, the time when horses seem to have been first domesticated in Asia, Professor Mithen’s thoughts are not on this momentous event but are murkily fixed on a swamp in New Guinea—Yuk Swamp (or Muk Swamp or Kuk Swamp… something like that) where excavators, up to their knees in mud, spent years grimly disinterring the mandibles of native swine.

Where classical archaeologists explored ancient civilizations, often managing to have themselves photographed with the ruins of Persepolis or whatever as a backdrop, and not infrequently enlisting Middle Eastern royals and their hangers-on as supernumeraries, men like Mithen are never happier than when rooting about in a bog discovering old animal pieces. Or faeces. They can tell you the precise dimensions of mammoth turds in a cave on the Colorado Plateau (as he does on page 244: they’re spherical and 20 centimeters across) but about the cavalry at Nineveh they know nothing at all. They simply wouldn’t have a clue that when “the Assyrian came down like a Wolf on the Fold”, as Byron says, the Assyrian wasn’t walking, and he wasn’t leading a goat or riding a pig—he was horsed.

Where classical archaeologists explored ancient civilizations, often managing to have themselves photographed with the ruins of Persepolis or whatever as a backdrop, and not infrequently enlisting Middle Eastern royals and their hangers-on as supernumeraries, men like Mithen are never happier than when rooting about in a bog discovering old animal pieces. Or faeces. They can tell you the precise dimensions of mammoth turds in a cave on the Colorado Plateau (as he does on page 244: they’re spherical and 20 centimeters across) but about the cavalry at Nineveh they know nothing at all. They simply wouldn’t have a clue that when “the Assyrian came down like a Wolf on the Fold”, as Byron says, the Assyrian wasn’t walking, and he wasn’t leading a goat or riding a pig—he was horsed.

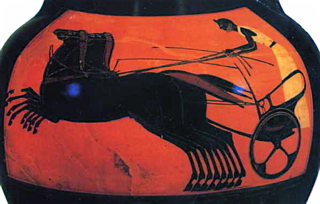

We might also point out for their benefit that Bucephalus (pictured with an embattled Alexander above) was not a cow, that Pegasus was not a goat with wings, and that the riders immortalized on the friezes of the Parthenon at the head of this article are not riding pigs—let alone guinea pigs. In the more glorious annals of humanity horses are important in ways that cows and goats and pigs are not. Horses matter, whatever Professor Mithen may think. It’s a pity one has to say this sort of thing but there it is.

Virgil

Virgil understood. And he also knew a lot about choosing horseflesh and chariot racing:

Notice a thoroughbred foal in the paddock—how from birth

He picks his feet up high, stepping fastidiously;

First of the herd he’ll venture onto the highroad, and ford

The menacing river, braving unknown dangers—

Nor will he shy at a meaningless noise. He shows a proud neck,

A finely tapering head, short barrel and fleshy back,

And his chest ripples with muscle: (bays and roans

Are soundest, white or dun horses the worst).

If he hears armour clang in the distance,

He can’t kept still, the ears prick up, the limbs quiver,

He drinks the air, he jets it in hot steam from his nostrils.

Now look! It’s a chariot race! They’ve charged from the starting-gate,

They’re galloping down the course all out, they’re covering the ground!

Each driver’s hope runs high; his heart is drained with terror,

Drumming with mad excitement: the drivers whirling their whips,

Leaning forward, giving the horses their head, the hot wheels flying,

Now ventre-à-terre they seem to travel, and then bouncing,

No slackening or respite: the course is a cloud of yellow dust,

The drivers are wet with the spindrift breath of the horses behind them.

So keen they are for the laurels, and victory means so much.

— The Georgics, Book III

Queensland rodeo

Last October I was in Warwick for the annual rodeo, staying at the Buckeroo Motel. Horse trailers and cattle trucks jammed the streets and were parked on every inch of ground. Out at the arena animal smells were strong and wet ground made them stronger. At 10.00am there was breakaway roping, followed by the Second Division Bull Ride, Team Roping, and the Junior Steer Ride.

Last October I was in Warwick for the annual rodeo, staying at the Buckeroo Motel. Horse trailers and cattle trucks jammed the streets and were parked on every inch of ground. Out at the arena animal smells were strong and wet ground made them stronger. At 10.00am there was breakaway roping, followed by the Second Division Bull Ride, Team Roping, and the Junior Steer Ride.

I learned that Queensland’s Warwick Rodeo had the best bucking stock in the business, and the best cowboys too, with Shane Kenny and Travis Young and Rod Thorpe all there. Shane’s jolly and confident face would make any steer think twice: he’d won 10 All Around Cowboy titles, while Travis had won over $16,000 and Rod did well in 2004 at Toowoomba and Tumbarumba.

The average length of a bull ride was about 2.5 seconds. From what I saw most riders bit the dust soon after the bull cleared the gate. It had been the same in 2004, and the Rodeo Association’s General Manager, Steve Hilton, said it was generally agreed last year’s bull riding was pretty ordinary. This year he was hoping for something better—10 seconds at least. Trophy buckles were offered for winners of the open events but this didn’t seem to help. The way I scored it was bulls 10, riders 0.

A youngster of 14 or so tried her hand at buckjumping, four other riders close by in case she fell and the horse tried to kick her head off. The cowgirls were smartly turned out—“c’mon Warwick give that girl a hand!” loudspeakers bawled— and when they weren’t riding round barrels they were breakaway roping or showing they could campdraft too. Ladies didn’t compete in the Wild Horse Racing though because this made a mess of your kit. A bunch of wild brumbies burst into the arena, and a cowboy “won” a race by being dragged along the ground past the finish point at the end of a rope. Or that’s what Wild Horse Racing looked like to me.

A youngster of 14 or so tried her hand at buckjumping, four other riders close by in case she fell and the horse tried to kick her head off. The cowgirls were smartly turned out—“c’mon Warwick give that girl a hand!” loudspeakers bawled— and when they weren’t riding round barrels they were breakaway roping or showing they could campdraft too. Ladies didn’t compete in the Wild Horse Racing though because this made a mess of your kit. A bunch of wild brumbies burst into the arena, and a cowboy “won” a race by being dragged along the ground past the finish point at the end of a rope. Or that’s what Wild Horse Racing looked like to me.

You could buy Ridetuff Jeans and special Contest Lace Up boots for yourself, with Skid Boots and Bell Boots and a Double Ear Rawhide Headstall for your horse. There were oxbows and bronc halters, quirts and shoo flies, caps and hats and hat holders (“Spring loaded loop that will not let hat slip out. Can’t bend or crush brim!”). Caps said “Cowgirl with Attitude”, “Rope tuff, ride tuff—just do it”, “Aggressive by nature, Cowgirl by choice”.

Yet there were signs of citification too. Roping tuff and riding tuff makes for pain at the end of the day, but the Medic 2000 digital micro system combines Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation and Electrical Muscle Stimulation for drug-free pain relief for sciatica, back pain, neck pain, knee pain, and sports injuries of every kind. Testimonials from riders confirm its value.

Then there’s the health of the horse. To help it “the natural way” you can feed it garlic and kelp, rosehips and fenugreek, nettle, dandelion root and chamomile. Chamomile is specially useful: “it is an important nervine that soothes, relaxes and calms a nervous horse especially those prone to loose manure due to nervous tension.” Equine herbalism is flourishing. Acupuncture is popular. Equissage is recommended for tired muscles if you really want to spoil the beast.

Around five in the afternoon I was ready to go. Seven hours was enough, and I’d spilled gravy down my shirt from a huge pork ’n onion submarine. I’d lost some glasses but still had my camera. “So where are we going?” said the cab-driver. “Back to the Buckeroo Motel?”

Prince and Greygo

with apologies to Steele Rudd

A good old horse Prince was, and how we revered him! He was our slave. All of us took a turn out of Prince, and drove him and rode him about without mercy. He was a great favourite of Dad’s—also of Mother’s. Mother wouldn’t drive behind any other horse but Prince. He was the only quadruped Mother would trust her life with. For twenty years we worked Prince hard on the farm, but one night he lay down behind the barn, and died, and we didn’t work him any more. Young Barty found him when he was dead, and while we were having breakfast rushed in and broke the news.

Prince is done fer! He’s pegged out.

Dad let fall his knife and fork.

What? The horse? he said with a look of astonishment.

Dad spoke as though he thought a horse should live on for ever.

Not Prince? Mother gasped, putting down her teacup.

Dead? Joe chuckled. Lyin’ down I ’spect.

Come and see then, Barty shouted. His legs is stiff, anyhow, and he’ll let y’ put y’ foot right on him.

Dad rose from the table and, bare-headed, went out to investigate. We rose and followed Dad. Barty was delighted with the commotion he had raised. It wasn’t often we took so much notice of Barty. He rushed into the lead, and disappeared behind the barn, and when the rest of us turned the corner he was standing triumphantly on the corpse, waving his hand about and looking like the statue of Captain Cook.

Dad stopped suddenly when he saw Barty, and murmured Well, well, well, well!

Dad seemed satisfied that the horse was dead. So did Mother.

Poor, poor Prince! she moaned. Poor Prince!

Dead all right, Joe said laconically, walking round and scrutinizing the body.

Didn’t I tell y’ he were, Barty chuckled cheerfully and, going off the brute’s ribs as he would off a spring-board, jumped in the air, and landing on the carcass again squeezed a melancholy groan out of Prince.

Confound you, get down off him! Dad burst out angrily. Get down, you scamp!

Barty got down in a hurry.

Clear away out of this altogether, Dad added, lifting a heavy stick from the ground. Barty bolted off like a hunted emu. You tinker! Dad heaved the stick after Barty, but it went wide of the mark.

Dad turned to Prince again, and once more said, Well, well, well, well!

Mother and Sarah sighed some more, then turned away, and we all went back to finish breakfast. We didn’t eat any more, though. We sat and talked of our bereavement.

It’ll be hard to replace him, Dad said sorrowfully, and left the table.

But as Steele Rudd tells his story, replace him they did. And what happened next shows that in horse-trading even more than in love and war, no-one knows what the morrow will bring. Farms being places where the Law of Unintended Effects is the only law you can count on.

Dad went into town and bought a fat, well-groomed grey horse called Greygo. Dad thought he’d got a great deal: the horse only cost three pounds ten. But they soon found he was a lot older than Dad imagined. And that was before they harnessed him to the cart.

He backed in easily, and then they were ready to go. Trouble was that backing is what Greygo most liked to do—but he wouldn’t go forward:

Joe lifted a greenhide whip from the bottom of the cart, and brought it down heavily on Greygo. Greygo responded instantly. He rushed backwards at an alarming pace, and Joe, taken by surprise, fell forward onto the animal’s back, and only saved himself from accident by getting astride it.

Mother and Sarah squealed, and ran to escape being run over. Joe struggled hard to force Greygo to reverse action. He dug his heels into him, then struck him between the ears with the handle of the whip. But Greygo went backwards all the faster.

Running backward the cart crashed into the water tank, made a big hole, and let all the water out. Dad got wet to the skin and tried kicking Greygo in the ribs, but nothing doing. Then Joe fashioned a whip from barb wire and tickled him up with that, and before long Greygo not only went forward, he rushed down a cutting, kicked the bottom out of the cart, threw Dad and Joe out onto some rocks, tipped the whole contraption over, broke out of his harness, and then stood in a pasture munching thoughtfully and surveying what he had done.

And that wasn’t the end of it—it gets worse. But here Steele Rudd himself takes up the tale.

Dad wouldn’t have any more to do with Greygo. Dad got rid of him. He swapped him to young Regan for a red heifer that had a cold, and a kangaroo dog. The red heifer gave four of our best cows tuberculosis, and the kangaroo dog killed twenty-five of our fowls and fourteen turkeys belonging to Thompson, and involved Dad in a lawsuit.

Swimming a river in Texas

from J. Frank Dobie

One trip with a herd across the Nueces came near being my last. It was dry time and there was no indication that the river would have much water in it, but when we struck it, some distance below San Patricio, we found it full from a head rise.

Before going into deep water, I generally undressed, or at least removed my heavy leggins, boots, spurs, and six-shooter. But there was no time here to take off anything. ‘Come on, muchachos’, I yelled, and spurred my horse into the water. He was afraid of it and turned back. The white boy with me and a Mexican who was an excellent swimmer then took the lead and I managed to make my horse follow.

When we were in mid-current a piece of driftwood floated under the nose of the Mexican’s horse, causing him to scare and wheel back. Immediately horse and rider both sank out of sight. The current was fearfully swift and there was a strong undertow. In a moment, however the Mexican and his horse bobbed up—right at my horse’s head and a little below.

My horse tried to shy, wheeled halfway around, and went under. I was not caught altogether off guard, and when I saw that the horse was going down I put one foot in the saddle and jumped as far ahead as I could, pointing upstream. On account of the uncontrollable disposition of my horse, I had not removed the bridle before putting him into swimming water; a moment after I left him he got one of his feet tangled in the reins, and while he drowned he turned over and over in the water, fairly making it boil.

Meanwhile the Mexican had got scared and quit his horse also. Despite the fact that he was an expert swimmer, he seemed unable to keep up and going. Presently he went down, not to reappear. Powerless to help, I had to watch both him and my horse drown.

My boots, leggins, spurs, six-shooter, and ducking coat seemed to weigh tons. I could not use my legs at all, but did manage to keep paddling with my hands. I shall always believe that my Guardian Angel held me up by the coat collar and helped me get to the bank. That was the hardest struggle I ever had in water, and I have tussled with every stream between the Rio Grande and the Platte.

Well, we held the herd, and the next day we found the body of the drowned Mexican far down-stream and also the drowned horse, his foot still tangled in the bridle reins.

— A Vaquero of the Brush Country

Working with camels and bullocks

Herbert M. Barker

When halting to boil the billy at midday, it was always a mistake to stop in loose sand. The camels would sit in it but immediately stand up again as the hot sand touched the tender parts underneath their bodies. They so enjoyed sitting down at midday that they’d try again and eventually cool the sand with their churning, but when finally sitting they might still suffer from a hot chain resting against the flank. Chains kept hot even in the shade, and the unfortunate camel had to push it away with the stifle of its back leg.

The soles of their feet can stand any heat, but above the sole there is a tender part carrying only short hair. If their feet sank an inch or two into heavy sand this part of the foot got burnt and they would then stamp as if ants were crawling up their legs. So at midday in really hot weather, we’d try to halt on smooth, hard ground. There the camel’s brisket would not sink in but hold the body well up, and the chains would lie level along the ground and clear of its skin.

The driver suffered in much the same way in the heat. He had to walk on the hot ground beside his camels while driving, and as he never wore socks there were always a few nails that conducted the heat of the ground to the bare soles of his feet. He sat under the wagon to eat his dinner but not before spreading a bag or some green gum leaves on the ground.

If the shaded axle was hotter than his hand could bear, then that meant 112 degrees or more in the shade. Another indicator of the temperature was the amount of tea one drank at midday. Weak tea with no condensed milk was the best drink, and sometimes I’d finish a whole billycan weighing five pounds. In those parts a temperature of 125 degrees in the shade is often recorded on a station verandah under a corrugated iron roof. At the Marble Bar post office the thermometer is in a stone building so the official readings are generally about three degrees lower, but after all few people live in stone buildings.

Thunderstorms used to interrupt carting, but they were regarded as a necessary evil as they gave water and camel feed. One of their favourite times seemed to be about two or three o’clock on a summer morning, and the camel driver had then to jump from his swag on the ground and unroll the tarpaulin over the wagon.

Often thunderstorms would come every night for two weeks and sometimes during the day. After heavy rain the boggy ground halted the carting, and if a wet season began the carting might cease for a month. Altogether, carting was not so profitable in summer as in winter, when the weather was nearly perfect. I can’t think of any pleasant feature of summer carting. Old hands would say as compensation: “It learns a man to appreciate the winter months when they come around.”

A camel driver was used to walking with his team all day, urging the lazy ones with the whip, calling to the leaders, and downhill working the brake… Horses in harness teams, rather than camels, occasionally suffered from what could be classed as cruelty from the whip, but only from the worst drivers. Horses are more tender than camels, bullocks, or donkeys, but being such brisk and honest workers they require less whip than other animals.

I was always puzzled why some teamsters, especially bullockies, swore so much at their animals. In hot weather it made one thirsty and let more dust into the mouth, and moreover it did more harm than good to a team. Every camel, or bullock, or donkey was given a name, and hearing it together with a stroke of the whip he soon learnt what was wanted when the driver addressed him by name without using the whip.

A driver swearing continually as well as calling the animals by name could get them into a muddle, so that the animals responded to swear-words that resembled their names, or failed altogether to distinguish their names. Most camel drivers gave up swearing and got better results, but bullockies kept up the tradition.

Even men working sheep used to swear at the sheepdogs. How they expected a dog to distinguish instructions from abuse when both poured out together would be hard to explain. One of the best bullockies in Queensland would swear at his son but not at his bullocks. He used to say: “What’s the good of swearing at bullocks when they don’t understand a word of it?”

Camels and the Outback

[Born in New Zealand in 1887, Herbert Barker spent some years as a camel carter in Western Australia. Between 1911 and 1929 he travelled vast distances between Meekatharra, Marble Bar, and Roebourne, carting supplies inland and bales of wool out to the coast. In his sixties and seventies he wrote about his experiences in a number of places and published two books, Camels and the Outback, and Droving Days.]

An Australian writer living in Sydney, Roger Sandall is the author of The Culture Cult (2001), a study of romantic primitivism and its effects. His work has appeared in a number of places including Commentary, The American Interest, Encounter, The New Criterion, The American, Sight and Sound, Quadrant, Art International, The New Lugano Review, The Salisbury Review, Merkur, Mankind, Visual Anthropology, and Social Science and Modern Society.

An Australian writer living in Sydney, Roger Sandall is the author of The Culture Cult (2001), a study of romantic primitivism and its effects. His work has appeared in a number of places including Commentary, The American Interest, Encounter, The New Criterion, The American, Sight and Sound, Quadrant, Art International, The New Lugano Review, The Salisbury Review, Merkur, Mankind, Visual Anthropology, and Social Science and Modern Society.