What’s with The Arabian Nights? How can we explain the lasting attraction of the mysteriously medieval East? The djinns? The camels? The metamorphoses? The alluring houris in dove-grey veils? Or could it be for some readers the vision of exquisitely delayed beheadings — so unlike the rude explosions of roadside bombs?

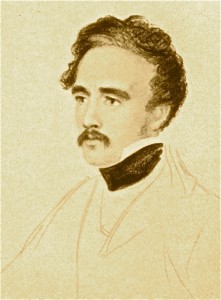

Whatever and however, in the 1820s young Benjamin Disraeli found The Arabian Nights an enchanting alternative to his life as a London law clerk — and he wanted out. Escaping from Swain, Stevens, Maples, Pearce and Hunt, and inspired by tales of Scheherazade, this dandified young man headed east where he dressed up as a pirate in “blood-red shirt, with silver studs as big as shillings,” and a sash stuffed with pistols and daggers. That was on a boat sailing from Malta to Corfu.

Whatever and however, in the 1820s young Benjamin Disraeli found The Arabian Nights an enchanting alternative to his life as a London law clerk — and he wanted out. Escaping from Swain, Stevens, Maples, Pearce and Hunt, and inspired by tales of Scheherazade, this dandified young man headed east where he dressed up as a pirate in “blood-red shirt, with silver studs as big as shillings,” and a sash stuffed with pistols and daggers. That was on a boat sailing from Malta to Corfu.

Then in 1839 Austen Henry Layard followed Disraeli’s example. With a travelling companion he too fled eastward, escaping both his uncle’s law office and his aunt’s literary salons. Only after crossing France and Italy, and reaching the shores of the Adriatic, did he feel able to fill his lungs and breathe freely at long last. In the company of another adventurer named Edward Ledwich Mitford, (Layard was 22, his companion Mitford 32) the two men planned to walk and ride all the way to India and Ceylon. But already as they rode along south of Trieste they could feel the grey burden of England lifting — and their spirits did too. Writing about it Layard told how delighted they were by the beauty of the Dalmation countryside in late summer, “and with the picturesque costumes of the peasantry, which seemed to increase in gorgeousness as we went south and approached the land of the Ottoman.”

Montenegro 1839 — a whiff of things to come

Their next stop was Montenegro. Layard tells in his Autobiography how they had received a letter from Montenegro’s leading chieftain, or Vladika, that “courteously invited” them not merely to visit but to stay with him in his palace at Cetinje. To ensure their safety the chief had sent horses and guards to escort his guests — “four savage but fine-looking fellows… presented themselves at our lodging. They each carried a long gun, and were armed to the teeth with pistols, yataghans, and knives.” These accoutrements added a spice of danger. Could they really be just ornamental? Or were they meant for serious use? But whatever the two young Englishmen made of this daunting arsenal they were entirely unprepared for what came into view at the palace. There “a circle of forty-five gory Turkish heads were stuck on poles, trophies from a battle the previous week.” For the last seven days they had been ripening outside the window of what became Layard’s sleeping quarters during his stay.

The Vladika (the combined prince-bishop of Montenegro) was a poet, and a man fond of learning and literature. He was delighted to find his English guests were too. It galled him that German newspapers had praised the courage of the King of Saxony, who had visited Montenegro in the course of a botanical excursion, for venturing into “the territory of a barbarous, sanguinary, and perfidious race”. This was simply untrue, he protested, pointing to a sign of his own civilized taste — the billiard table he had recently installed — but one fine day while he and Layard were chalking their cues they were interrupted by a clatter of hooves outside, with much shouting and firing of guns. Some Montenegrin warriors had been on a foray into Turkish territory and had returned with a present for their leader. Layard writes in his Autobiography:

They carried in a cloth, held up between them, several heads which they had severed from the bodies of their victims. Amongst these were those apparently of mere children. Covered with gore, they were a hideous and ghastly spectacle. They were duly deposited at the feet of the Prince, and then added to those which were already displayed…

Then and later Layard’s political sympathies were with the Turks. Russian despotism was the main enemy: the Sultan, however decadent his administration, deserved British help resisting it. This accorded with long-term British policy that saw the Ottoman Empire as a necessary bulwark against Russian expansion to the south. Yet the trophies on display outside the palace in Cetinje must surely have given pause — must have provided at least some sense of leaving behind not only the London law office he despised, but law itself; of having crossed a frontier separating civilization from the tribal past.

Then and later Layard’s political sympathies were with the Turks. Russian despotism was the main enemy: the Sultan, however decadent his administration, deserved British help resisting it. This accorded with long-term British policy that saw the Ottoman Empire as a necessary bulwark against Russian expansion to the south. Yet the trophies on display outside the palace in Cetinje must surely have given pause — must have provided at least some sense of leaving behind not only the London law office he despised, but law itself; of having crossed a frontier separating civilization from the tribal past.

Not long ago Samuel P. Huntington pointed to the fault-lines dividing cultures, and on page 159 of his well-known book he provides a map of “The Eastern Boundary of Western Civilization”. Running southward from the Russian shores of the White Sea, it bisects a number of countries in Eastern Europe before passing through Montenegro to end in the Adriatic. Layard was on his way to Mosul in Mesopotamia, and the unearthing of the Assyrian remains of Nimrud and Nineveh that would be forever associated with his name. Both in antiquity, and in the 1840s, he would discover there a markedly cavalier attitude toward both human life and human heads — especially in the region we now call Iraq.

Enter The Arabian Nights

A paradox was becoming obvious. On the one hand picturesque peasants, colourful textiles, novel dishes to whet the appetite, followed by exciting music and dance. On the other, grisly customs and diabolical politics. For romantic aesthetes the discovery that in tribal societies the appealing and the appalling are often inseparable always comes as a disappointing surprise. In Layard’s case, one wonders how such an exceedingly cultured young Englishman understood so little — less indeed than ordinary German newspaper readers might expect to know in 1840 — about the ‘barbarous, sanguinary, and perfidious’ political customs east of Huntington’s line? In short, knew so little about lands, unlike his own, where life is cheap and where both civil and civilised law is thin on the ground.

His formal education had been patchy, and his childhood experience of various schools in England and on the continent had been miserable. Tri-lingual, in France he was tormented for being English; in England he was persecuted as a “frog”. He was only truly happy in Florence, where the family went for nine years hoping that a change in climate would restore the health of his asthmatic father Peter. It was in Italy that Peter Layard took his son to galleries where he learned to appreciate the Masters, and it was there the boy first read Shakespeare, Spenser, and Ben Jonson. But these proved of minor interest — he was spellbound by something else.

“The work in which I took the greatest delight,” he wrote, “was ‘The Arabian Nights’.” In their apartment within the Rucellai Palace, the Layard family home in Florence, “I was accustomed to spend hours stretched upon the floor, under a great gilded Florentine table, poring over this enchanting volume. My imagination became so much excited by it that I thought and dreamt of little else but ‘djinns’ and ‘ghouls’ and fairies and lovely princesses, until I believed in their existence…” Moreover, he adds, “My admiration for ‘The Arabian Nights’ has never left me. I can read them now (he was writing this late in life) with almost as much delight as I read them when a boy. They have had no little influence upon my life and career; for to them I attribute that love of travel and adventure which took me to the East, and led me to the discovery of the ruins of Nineveh.” [For more on his youth and boyhood see also Young Layard of Nineveh]

Layard’s sympathy for the Turkish cause was not unique. On the same voyage that found him sailing so splendidly dressed between Malta and Corfu, Benjamin Disraeli tried to help Turkey suppress a rebellion in Albania. His biographer Robert Blake tells us that the revolt was over before Disraeli was ready, but that he nevertheless went to Janina in north-western Greece “to congratulate Reshid Pasha, the Grand Vizier, who was in command of the Turkish army.” Disraeli was both a friend of Layard’s uncle Benjamin Austen, and a regular visitor to his aunt Sara’s salons. He wrote excitedly to Austen: “For a week, I was in a scene equal to anything in the Arabian Nights. Such processions, such dresses, such cortèges of horsemen, such caravans of camels!”

In Constantinople he found “the meanest merchant in the Bazaar looks like a Sultan in an Eastern fairy tale”, adding in another letter to Austen that “All here is very much like life in a pantomime or Eastern tale of enchantment, which I think very high praise.” In the opinion of Gordon Waterfield, author of the biographical Layard of Nineveh, Disraeli’s thrilling stories about his travels in the 1830s influenced Layard as much as the tales in the Arabian Nights itself: both encouraged romantic dreams of the East — an aesthetic vision that far outweighed any political misgivings.

Only a short time after the grim experience of Montenegro, having crossed into Turkish Albania and arrived at the city of Scutari (modern Shkodër), Layard was enthusing about the colourful life of an eastern bazaar. He was pleased to find that the dress and manners of European civilization “had scarcely penetrated into the realm of Islam” and that he felt he had at last passed into “a world of which I had dreamt from my earliest childhood.” Once more he sees the ferocious weaponry men habitually carry, not as a symptom of lawlessness, or the absence of civil society, but as largely decorative. In fact he treats it on much the same level as cuisine. In the bazaar he is delighted to encounter

The jaunty Albanian with his white fustanella and his long gun resplendent with coral and silver, his richly inlaid pistols and his silver-sheathed yataghan, the savoury messes in the cook’s shops… etc.

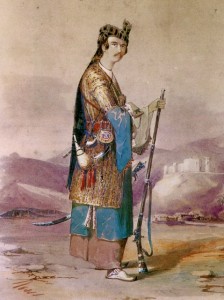

From Constantinople he sent a letter to his Aunt Louisa that might have come from Disraeli himself: “With this place I am much delighted. It even exceeds any description I have seen. The imagination could not picture a site more beautiful as that occupied by Constantinople. In the hands of any other European Power it would have been the strongest city in the world; in the hands of the Turks it has become the most picturesque.” The costumes of the Dalmation peasantry are picturesque; the city of Constantinople is picturesque. It also became necessary for this fugitive from a London solicitor’s office to proclaim his new identity in a suitably picturesque way. Two of the most commonly reproduced portraits of Layard as a young man show him “in Albanian Dress”, by W. H. Phillips, and “in Bakhtiari dress”, a watercolour painted in Constantinople by Amadeo Preziosi in 1843.

From Jerusalem to Petra and back

At Antioch Layard had seen the springs associated with Daphne and the remains of what may have been the temple of Apollo. On the way to Aleppo he found reminders of Crusader days — churches, convents, and castles. In Jerusalem he was determined to see the strange rock-carved architecture of Petra, and explore the lands of Moab and Jerash. There was however a small problem: south of the Dead Sea the whole countryside was in disorder following an invasion by Egyptian armies under the famous Muhammad Ali Pasha. The British Vice Consul warned Layard that he’d be attacked and plundered by Bedouin who would strip him naked and leave him for dead. Upon hearing this the prudent Mitford declined to go: he would wait for his companion (assuming Layard survived) in the safety of Damascus.

At this stage Layard knew no Arabic, and the area where he was going was infested with Bedouin who lived by robbing and murdering anyone they could find on the roads. But none of this dimmed the glowing vision of the desert tribes he had acquired from the writings of the Swiss traveller Johann Ludwig Burckhardt. According to Burckhardt the Bedouin lived in tents; they were people of virtuous simplicity and simple virtues; and their natural hospitality meant that a traveller could happily trust them with his life. Defying augury, Layard hired an interpreter and set off. Later he confessed:

I had romantic ideas about Bedouin hospitality and believed that if I trusted to it, and placed myself unreservedly in the power of the Bedouin tribes, trusting to their respect for their guests, I should incur no danger. I did not know that the Arab tribes who inhabit the country to the south and east of the Dead Sea differed much from the Bedouins of the desert, of whom I had read in the travels of Burckhardt, and that they fully deserved the evil reputation they had acquired in Jerusalem.

The consequence of placing himself unreservedly in the power of armed and dangerous brigands, however picturesquely dressed, was not what he hoped. After skirmishes with drawn swords, and confrontations at pistol-point, half-starved, exhausted, robbed of books, papers, medicines, his beautiful robe of Damascus silk and most of his clothes, wearing only an “Arab cloak, now almost in tatters and not worth taking,” he dragged himself into Damascus to meet the British Consul. Exactly what the Consul thought is unclear. But he kindly offered his countryman some tea.

On to Baghdad

Now somewhat less trusting, and a lot more wary, Layard next took the road to Mosul. “We rode during the whole day through a desert plain… constantly on the look-out for Bedouins…” Then in Mosul the future archaeologist came face to face with destiny. On the banks of the Tigris were the long-buried remains of Nineveh, the ancient city where he would make his name. Although it would be five long years before he was allowed to begin digging, and all he could see were vast enigmatic mounds, “I was deeply moved by their desolate and solitary grandeur”, he wrote, and spent a week in the area taking measurements and looking for inscriptions.

The dress, manners, and political institutions of European civilisation had scarcely penetrated into this Islamic realm at all — presumably a huge plus — but Layard was beginning to understand the limitations of Turkish rule. His lodgings were on the Mosul side of the Tigris. Nineveh was on the other. There had once been a bridge, but it had been swept away long ago, “and, under the careless and fatuous rule of the Turks, no attempt had been made to replace it.” It was also obvious that the consequences of Ottoman government were more serious than a mere indifference to roads and bridges. The town of Mosul was governed by “a Pasha of the old school, almost independent of any control… who could oppress the subjects of the Sultan under his rule, extort money from them, and reduce them to utter ruin and misery with impunity.”

But these imperfections seemed ignorable: at Mosul all the old childhood emotions and memories of books read under the gilded Florentine table came enjoyably flooding back. The approach to Baghdad by water as he floated down the Tigris delighted the senses. Beneath tall and graceful date palms “were clusters of orange, citron, and pomegranate trees, in the full blossom of spring. A gentle breeze wafted a delicious odour over the river, with the cooing of innumerable turtle-doves. The creaking of the water-wheels, worked by oxen, and the cries of the Arabs on the banks added life and animation to the scene. I thought that I had never seen anything so truly beautiful, and all my ‘Arabian Nights’ dreams were almost more than I realised.”

Yet where every prospect pleases man can be uncommonly vile. Layard had been warned of Arabs along the banks of the river that “would rob and plunder us if we ventured to land”. When somewhat surprisingly this did not happen, he soon found why — it was because a highly disagreeable penalty for robbery had been imposed by the previous Pasha. In Baghdad there had been a rule of uncompromising punitive terror. The Bedouin had been kept under control and the roads kept safe by “the horrible punishment of impalement.” There was a bridge of boats across the river, and the former governor, a man proud of his province and determined to defend the progress he had made from inveterate criminals, “was in the habit of placing them on stakes at the two ends of the bridge of boats, and on either side of it, as a warning to those who visited the city and had to pass between them.” A British resident in Baghdad, Dr. Ross, had recently seen four offenders thus exposed. Bear in mind this was 1840, not 1480.

Joining the Bakhtiari

In Baghdad Layard spent his days exploring Babylonian ruins, and looking at the fine collection of Arabic and Persian manuscripts in the library of Colonel Taylor, the Political Resident of the East India Company in Baghdad. But soon his mind turned toward the region of the southern Zagros mountains, a territory vigorously contested between the Bakhtiari tribe, who pretty much controlled things on the ground, and the Shah in Tehran who claimed sovereignty. To do this however meant dealing with the Persian governor of Isfahan, Manuchar Khan, a man who had recently shown he was not to be trifled with by building a tower out of 300 prisoners, mortared together like bricks, who all died slowly and hideously.

About this time Mitford decided that his travelling companion was incorrigible. If Layard was now going to defy Manuchar Khan and throw in his lot with the Bakhtiari — a tribe regarded by Tehran as “a race of robbers, treacherous, cruel, and bloodthirsty”, that Governor Manuchar Khan plainly intended to crush — then he wanted none of it. Edward Mitford now journeyed on to India alone, while Layard turned his mind to the months ahead. In a full-blooded romantic outburst he wrote to his uncle-solicitor back in London (on whom by the way he entirely depended for funds) that he was sick of the civilised and semi-civilised world and lived “happier under a black Bakhtiari tent with liberty of speech and action and nobody to depend on, no-one to flatter, certain that I shall have dinner tomorrow — for there is always bread and water — and without need of that source of all evil, money…”

In his memoir about these days Layard was however more calculating. He wrote that despite the bad reputation of the Bakhtiari “I was very hopeful and very confident that my good fortune would not desert me, and that by tact and prudence I should succeed in coming safely out of my adventure. I determined at the same time to conform in all things to the manners, habits, and customs of the people with whom I was about to mix, to avoid offending their religious feeling and prejudices, and to be especially careful not to do anything which might give them reason to suspect that I was a spy.”

His confidence was justified — he soon fluked his way into the patronage of a great and powerful Bakhtiari chieftain, Mehemet Taki Khan, a man able to command a force of 10,000 men. In the fortress of Kala Tul the Khan’s ten-year-old son lay dying of fever. He was at the point of death, and “the father appealed to me in the most heartrending terms, offering me gifts of horses and anything that I might desire if I would only save the life of his son.” Taking a huge chance Layard gave the patient some quinine. Within hours the boy broke into “a violent perspiration”; by dawn he was on the way to recovery; after this Layard found himself welcomed into the most intimate areas of Bakhtiari domestic life, and even lodged in the residential inner sanctum or enderun (harem) itself.

No longer a solitary alien on the outside, perpetually having to explain himself and at risk of being murdered on the road, his position was suddenly reversed. Now he was on the inside, and tribal life looked increasingly like the warm and hospitable world he had fantasised about for so long. It is not impossible that in these days he may from time to time have been romantically involved with Bakhtiari women. They found him attractive, and he was certainly attracted to them. After saving her son’s life Layard tells us that the Khan’s wife “treated me with the affection of a mother”, while he described her sister Khanumi as the most beautiful woman in all the tribe: “Her features were of exquisite delicacy, her eyes were large, black and almond-shaped, her hair of the darkest hue; she was intelligent and lively.”

Urged by the Khan to convert to Islam and marry Khanumi, Layard resisted, though he told his aunt that the Bakhtiari custom of sigha interested him: it enabled a man “to marry for a period, however short — even for twenty-four hours — and which makes the contract for the time legal.” The marital arrangements of the Khan himself seemed ideal. He married and divorced monthly, enjoying a continual honeymoon. It is perhaps not entirely irrelevant that in the Arabian Nights, before Scheherazade found a beguiling way around it, the Sultan had married, enjoyed, and then calmly killed each of his ‘wives’ next day.

Lord Curzon described Layard’s account of life among the Bakhtiari as “one of the most romantic narratives of adventure ever penned.” He not only joined the tribe, he mastered their Persian dialect and participated in their lion hunts, their feuds, and their battles with Persian authority. This did not go unnoticed. Upon learning of Layard’s active participation in skirmishes with Persian troops, the Vizier in Tehran told the British Ambassador Sir John McNeill, who inquired after his whereabouts: “That man! Why, if I could catch him I’d hang him. He has been joining some rebel tribes and helping them.”

At the gates of Baghdad

Anyway it was tremendous fun living amidst forays, feuds, and death by the assassin’s hand, or sitting long into the small hours listening to stories told by men “constantly engaged in bloody quarrels arising out of questions of right of pasture and other such matters. When they were thus at war they ruthlessly pillaged and murdered each other. With them ‘the life of a man was as the life of a sheep,’ as the Persians say, and they would slay the one with as much unconcern as the other.” The excitement of life in the great chief’s fortress was all very well as long as Taki Khan was in control and the Persians were not. But it couldn’t last. Manuchar Khan was determined to break and punish the Bakhtiari, the clans sensed it, and before long their fealty weakened and the chief’s followers began to melt away.

In a land where oaths were lightly given and lightly broken, Mehemet Taki Khan soon found himself beleaguered and on the run. As for Layard, confined by Manuchar Khan in the city of Shustar for helping the Bakhtiari, he boldly escaped and made his way back through parching deserts and fearful heat to Baghdad. Attacked and thrown from his horse by marauders of the Shammar tribe, Layard lost the disguise of his Arab keffiya (or cloth headdress) and was mistaken for a hated Osmanli.

“One of the Arabs cried out that I was a ‘Toork’, and a man who had dismounted drew a knife and endeavoured to kneel upon my chest. I struggled, thinking that he intended to cut my throat, and called out to one of the party who, mounted upon a fine mare, appeared to be a sheikh, that I was not a ‘Toork’ but an Englishman.” The sheikh relented, mistaking Layard for Dr. Ross of Baghdad, and again Layard

escaped with his life — but most of his clothing, his watch, compass, and his last few silver pieces were lost. When he reached Baghdad it was Damascus all over again. Lying alone at dawn in the dirt outside the city gates, waiting for them to open, clad in rags and with bare and bleeding feet, “overcome by fatigue and pain”, he was ignored by parties from the British Embassy who rode by without recognising him — nor did he hasten to make his presence known. But following behind them came Dr. Ross:

I called to him, and he turned towards me in the utmost surprise, scarcely believing his senses when he saw me without cover to my bare head, with naked feet, and in my tattered ‘abba’.

From Arabian Nights to Assyrian Horrors

Layard’s experiences along the Turko-Persian border made the young adventurer an authority on the geographical issues involved — when it was in his possession he put his compass to good use. This drew the notice of the British Ambassador in Constantinople, Sir Stratford Canning, who in 1842 made him an unpaid attaché at the Embassy. In 1845, after much hesitation, Canning allowed Layard to commence the excavations that led to the discovery of several long-buried palaces, including that of Sennacherib.

The subsequent achievements of Sir Austen Henry Layard, as he eventually became, were prodigious — excavating an enormous site, making remarkable drawings of the palace sculptures, mastering cuneiform, firmly responding to the continual obstruction of his work by venal and mendacious Pashas, transporting both the palace reliefs and two colossal stone bulls down the Tigris — all the while fighting off armed marauders who, both at the diggings and while rafting the reliefs downriver to Basra, were always waiting their chance.

Turning the yellowed leaves of his 1853 folio publication The Monuments of Nineveh, the dry and disintegrating leather of its old Morocco binding falling apart in one’s hands, one may learn from Layard’s drawings much about ancient Mesopotamia. Plates 8 and 9 show dates, apples, grapes and pomegranates being carried to a royal banquet, and groves of palms, and one can easily imagine a gentle breeze wafting the scent of citron across the river, for the noble Tigris ripples through many scenes. But soon the images become more sombre. Hundreds of prisoners, criminals, and naked slaves, harnessed by long ropes to sledges on which great stone bulls were being moved, are seen with overseers, their arms always threateningly upraised to lash and beat.

And then in Plate 21 something else catches the eye — as perhaps it was meant to by the Assyrian architect who placed it near the middle of a scene. The relief sculptures show Sennacherib’s destruction in 701 BC of the city of Lachish, in the Kingdom of Judah. We are presented with three captives impaled on stakes. There are also scenes of beheadings, and of government scribes counting piles of heads, and of prisoners being flayed alive. Today sensitive museum administrators are a little shy about this sort of thing, preferring to keep it out of sight, but Layard himself was unflinching. Some prisoners, he wrote,

had been condemned to the torture, and were already in the hands of the executioners. Two were stretched naked at full length on the ground, and whilst their limbs were held apart by pegs and cords they were being flayed alive. Beneath them were other unfortunate victims undergoing abominable punishments. The brains of one were apparently being beaten out with an iron mace, whilst an officer held him by the beard. A torturer was wrenching the tongue out of the mouth of a second wretch who had been pinioned to the ground. The bleeding heads of the slain were tied round the necks of the living who seemed reserved for still more barbarous tortures.

Today we can only wonder at the historical echoes across nearly 3,000 years. That civil society never developed in the region is an anthropological puzzle where culture, psychology, intransigent tribalism, military imperatives and religious belief, are probably all involved. It is also a political puzzle for which we are unlikely to find a solution anytime soon.

[The above is a variation of “Layard of Nineveh,” an article in the July/August 2010 issue of The American Interest. www.The-American-Interest.com]

Note: Substantial excerpts from Layard’s writings, mainly Early Adventures and Autobiography, are here: Young Layard of Nineveh. For a discussion of more recent regional issues, and the political influence of Lawrence of Arabia, see also Nihilism in the Middle East.

Reading

Blake, Robert. 1966. Disraeli. London, Eyre and Spottiswoode.

Larsen, Mogens Trolle. 1996. The Conquest of Assyria. London and New York, Routledge.

Layard, A. H. 1853. Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon… London, John Murray.

Layard, A. H. 1853. Monuments of Nineveh, V. 2. London, John Murray.

Layard, A. H. 1894. Early Adventures in Persia… London, John Murray.

Layard, A. H. 1903. Autobiography and Letters… London, John Murray.

Waterfield, Gordon. 1963. Layard of Nineveh. London, John Murray.

Reply to Comments

Lighten up guys! You might just be missing the point. Arabian Nights, Baghdad Days offers all-too-typical scenes from the human comedy — in this case the long-running farce of East meets West. Nice clean-living London law student reads a book of tall tales, ships out to Turkey so he can dress up and meet princesses and ride on magic carpets through the sky… Then crashes to earth and is lucky not to lose his head.

Shakespeare could have done something with it and given Will Kemp a role. Or Cervantes — Layard’s delusions are as crazy as Don Quixote’s. Or perhaps Voltaire: the naivete of young Austen Henry Layard reads like Candide among the Ottomans. Anyway the adventures described provide a hilarious metaphor for Western delusions about the historic cultures of the region — fantasies whose consequences, as we can see today in Iraq and Afghanistan, are sometimes not funny at all.

That’s what 99.9% of the article is about. Not some definition from Sociology 101. So imagine my surprise when I find the only items discussed are two words, “civil society”, occurring in the final paragraph. A speculation ruminatively tacked on the end.

Civil society (for me pretty much synonymous with civilized society) is the only social order that satisfies the hopes, values, and understandings of the modern mind. That is the broad subject under consideration. It does not exist in Iraq today and it never did. Sufi lodges and madrassas, like the local donkey market and a thriving carpet trade, just don’t cut it. Sorry. They all belong to an intensely parochial and limited world, whose freedoms, both mental and political, are crippled by local cultural constraints and enduring religious fixations that make it difficult for the region to move on.

But let’s begin at the evolutionary beginning… More simply and just by way of adumbration, in civil societies the butcher, the baker, and the candlestick maker count themselves lucky because after hundreds of years they’ve at last got out from under the feudal lord, the military caste with its blood-thirsty warriors, the raving mullah with his dogmas and constraints, the clan and the tribe with their xenophobic prohibitions and endless fighting; and last but not least, the political regime of “ruler takes all” with its Khans and Kings and Emperors.

That goes for the wives of the butcher and baker and candlestick-maker too. If the western butcher’s wife wants to take a course in accountancy she can — whatever her clan or tribe or priest or president might think. If the wife of the baker wants to get away from the oven and an offensive husband too, then civil law allows this, because opting out is protected; indeed, the freedom of individuals to achieve their destinies according to talent and opportunity — not according to ascribed features of tribe or skin color or sex or dynastic connection or prophetic affiliation (Shia, Sunni) — is an intrinsic feature of this historically novel and belatedly evolved social order.

“Old-fashioned” you say? Well, yes, I suppose the subject of civil society is that, since the puzzle why East is East and West is West — including why Oriental Despotism repels and why no thinking man or woman wants a bar of it — runs all the way back to Aristotle. And by the way, minds a lot more powerful than Edward Said’s have pondered the issues involved, from Adam Ferguson and Gibbon in the 18th century, to Marx (the Asiatic Mode of Production) and Sir Henry Maine (status vs. contract) in the 19th century, to the summarizing discussion provided by Ernest Gellner at the close of the 20th — Conditions of Liberty: Civil Society and its Rivals.

For Gellner, as for Aristotle, freedom is the crux of the matter and ultimately the point of it all: “Traditional man can sometimes escape the tyranny of kings, but only at the cost of falling under the tyranny of cousins, and of ritual.” Rephrased somewhat (RS): “tribal man must choose between the tyranny of despots, from Sargon to Saddam, or the straitjacket of kinship groups and the equally confining intellectual dogmas of priests.” The legislative framework of civil and secular modernity enables independent men and women to defy political autocrats, domestic tyrants, and religious dogmas, all at the same time — the admirable and courageous Ayaan Hirsi Ali provides a heroic example.

What are the conditions for escaping these assorted tyrannies — an escape Mesopotamia never made? They are largely economic (just as Ayaan Hirsi Ali today could never have found a way out of her Somalian straight-jacket without alternative, non-tribal sources of financial support). The short answer describing a very long process is in Gellner’s words “perpetual and exponential growth”: in this process the commerce and production of free economic agents supersedes predation, replacing the exactions of warrior castes and the forced internal and external tribute of the state.

This alternative route to prosperity requires private property, along with civil law, and other legislative protections allowing wealth to accumulate or be used to best advantage by free citizens — not tribesmen or slaves or serfs or fanatically fierce sectarians murdering each other day after day. Without it, all you tend to get is the chronic instability of a three-cornered contest for power between the state, the tribes, and the sects, as Gellner says.

So what do I mean by civil and civilized society? In brief, a social order where citizens are guaranteed freedom of movement, freedom of association, freedom of belief, freedom to pursue economic opportunities as they arise and to keep or use whatever capital accumulates as a result, freedom from obligatory state service — along with the separation of church and state, the right to think whatever you like without being blown up or having your head cut off, and government by the consent of the governed with appropriate electoral procedures.

It would be wonderful if you could find these desirable features shining out in Mesopotamia’s long and notable past. Perhaps here and there you can. But there was no Greek Enlightenment, or game-changing debate about the nature of justice, citizenship, and the duties of government. No Magna Carta. No Renaissance. No Reformation. No relief from religious obsessions, dating back to Ishtar and Asshur, with their persistent theocratic temptations. The political panorama of Mesopotamian history shows little but the dynastic rise and fall of despots and their vassals, rulers whose Ozymandian pretensions stretch from Sargon to Saddam with their armies and captives and slaves, shouting their conquests brazenly from stelae, proudly displaying their grisly triumphs in sculptured panels of military violence, enslavement, punishment, and submission. Shelley got it in one.

RS

An Australian writer living in Sydney, Roger Sandall is the author of The Culture Cult (2001), a study of romantic primitivism and its effects. His work has appeared in a number of places including Commentary, The American Interest, Encounter, The New Criterion, The American, Sight and Sound, Quadrant, Art International, The New Lugano Review, The Salisbury Review, Merkur, Mankind, Visual Anthropology, and Social Science and Modern Society.

An Australian writer living in Sydney, Roger Sandall is the author of The Culture Cult (2001), a study of romantic primitivism and its effects. His work has appeared in a number of places including Commentary, The American Interest, Encounter, The New Criterion, The American, Sight and Sound, Quadrant, Art International, The New Lugano Review, The Salisbury Review, Merkur, Mankind, Visual Anthropology, and Social Science and Modern Society.