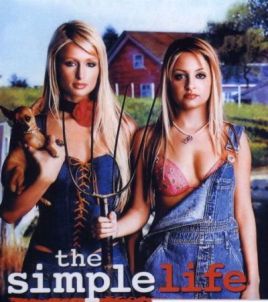

It’s a shame really. Paris Hilton could easily give sluttishness a bad name. I don’t mean just the video that’s available—I mean the chilling vacuity: it’s enough to give Casanova the wilts.

But that’s by the way. My darker purpose here is to see how the ethical world of Grant Wood’s 1930 painting American Gothic, with its moral Puritanism and devotion to hard work, could be adapted and parodied for TV trash starring rich party girls and poor dumb animals in the year 2003.

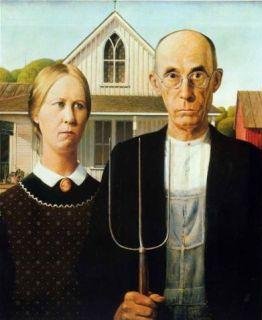

Can we read something about the direction of modern America in this transmogrification? The original painting (below) shows a man, a woman, a fork, and a house. The woman looks aversively away. The man stares out with primitive religious force, and one might easily think that as long as the beliefs behind his eyes endure, as long as he has moral convictions, America will endure.

One might also think that when those beliefs are replaced by a bland and directionless amorality, by the world of a Bill Clinton on the one hand or a Paris Hilton on the other—by decadent hedonism pure and simple—in brief, when the fire behind those eyes goes out and all religious belief is lost… But here conjecture falters and for the time being had best stay mute.

Genesis

The basic facts about the painting are straightforward. In 1930, in the town of Eldon, Iowa, Grant Wood painted his sister Nan and his dentist Byron McKeeby standing in front of a wooden house with a Gothic window. McKeeby was asked to hold a three-tined hayfork in his hand.

Wood had wondered who to use as the woman in the painting (Nan’s face was too fat, he thought at first, before deciding to slim her features down), and he had trouble persuading the dentist to pose (McKeeby finally agreed to stand in his dental rooms while the artist painted), but when it was done he entered the work in the 1930 Exhibition of American Paintings and Sculpture held at the Art Institute of Chicago. It won him a bronze medal and $300.

In Steven Biel’s wonderfully detailed history of the painting and its place in the American psyche (American Gothic: a Life of America’s Most Famous Painting, Norton 2005) he tells how it was originally rejected. But an Art Institute trustee found it on the discard pile and insisted that it be included in the Exhibition. Thus it was, as Biel writes, that “an image familiar to almost everyone might have been seen by almost nobody. A painting that became a national icon nearly got sent back, barely noticed, to Iowa.”

Three years later, in 1933-34, the Chicago World’s Fair celebrated “A Century of Progress” with its own art exhibition. One and a half million people trooped in to see the show. The strongest attraction seems to have been “Whistler’s Mother”, but American Gothic ran it close, and prints of Wood’s painting outsold everything else. By then it was becoming known nationwide, and the Des Moines Register later joined various art critics in decreeing American Gothic the most popular canvas on exhibit at the World’s Fair.

Caricature?

Which isn’t to say everyone liked it—Iowa’s farmwives assuredly did not. They thought they were being caricatured. The couple were too “grim-visaged”, too sad and serious. Mrs Inez Keck of Washta said they looked “inordinately solemncholy” and might have been to a funeral. Mrs Earl Robinson, from the Iowa town of Collins, declared that being true to life wasn’t good enough and that next time around the painter should “choose something wholesome to look at and not such oddities. I advise him to hang this portrait in one of our fine Iowa cheese factories. That woman’s face would sour milk.”

This however is the normal verdict of people who find that artists don’t always see them as they see themselves. Like the rest of us they are distressed by an unflattering portrait. More embarrassing than this reaction—and more to the point of our discussion—was its initial succès d’estime with critics—the enthusiastic embrace of all those who wanted to see mid-western Puritanism and philistinism (if not religion itself) both ridiculed and destroyed.

“No less an authority on modern art than Gertrude Stein”, writes Steven Biel, “whose opinions the American Press eagerly reported in the 1930s, praised Wood as ‘the foremost American painter’ and declared, ‘We should fear Grant Wood. Every artist and every school of artists should be afraid of him, for his devastating satire.”

The critic Walter Prichard Eaton was also sure of Wood’s satirical intentions, and though he admittedly knew nothing about the artist or his history, wrote in 1930 that when he looked at the couple in American Gothic

We cannot help believing that as a youth he suffered tortures from these people, who could not understand the joy of art within him and tried to crush his soul with their sheet iron brand of salvation. They are rather terrible. The longer you look at them, the more you realize they might come from many parts of this country—but from no other.

The notorious hostility between Art and Main Street led Saturday Review of Literature critic Christopher Morley in 1931 to speculate about the couple’s “sad yet fanatical faces”—faces revealing a deep animosity toward creativity and culture. Some fifteen years later H. W. Janson, later to become known as author of the widely used History of Art (1962), would write that American Gothic “had been intended as a satire on small-town American life”; another critic would claim in 1974 that its figures “exude a generalized, barely repressed animosity that borders on venom” and symbolize “the malevolent spirits that inhabited this region”; while in 1997 Robert Hughes announced that it was both satirical and nervously oblique. Biel writes that according to Hughes

“Wood was a timid and deeply closeted homosexual”, and American Gothic, rather than offering up a forceful, unambiguous, straight, or uncloseted satire, was “an exercise in sly camp, the expression of a gay sensibility so cautious that it can hardly bring itself to mock its objects openly.”

Open and unambiguous mockery of philistinism and Puritanism in the manner of Mencken—for whom Puritans and philistines were the “twin blights of American civilization”—being needed if the world were to be set to rights.

Wood’s intentions

Yet the notion that a painting of two ordinary Iowa citizens must either celebrate them or damn them doesn’t make much sense. Wood’s intentions must have been a good deal more complicated than either his hometown critics or his bohemian admirers understood. But they are not obscure. They are in fact perfectly clear to anyone who comes from a conventionally respectable home; who takes up art, travels abroad, and explores bohemia; and who then returns sadder and wiser to the world he knows. Such an artist sees more deeply, and his affection is refracted through experiences that partly distance and disenchant—but he respects what he knows and sees and does not plan to destroy it.

This seems to have been the case with Grant Wood. He was born in Iowa, in 1891, in Jones County near Anamosa. Steven Biel tells us his people were Quakers, and when a neighbor lent them Grimm’s Fairy Tales his father returned it unopened because, he said, “We Quakers can read only true things.” In 1901 his father died and the family moved to Cedar Rapids. There “he milked neighborhood cows, sold vegetables from his mother’s garden, and delivered drinking water to help support the family.” At school he developed an interest in arts and crafts, and drew for the yearbook and the school magazine.

There was an artist’s colony in Cedar Rapids—Wood himself is said to have once described it as “the Greenwich Village of the Corn Belt… the only truly Bohemian atmosphere west of Hoboken”—and after joining it for a while he made a number of visits to Europe in the 1920s. Biel says that in France in 1923 and 1926 he produced a lot of “derivative Impressionist paintings that sold poorly at an exhibition at the Galerie Carmine”, and that about the only thing that endured from “his exposure to late nineteenth-century French painting was the influence of Georges Seurat’s pointillism.”

But a 1928 encounter with Weimar and its “disgust, cynicism, and social criticism” was too much. “I’m going home for good,” he told William Shirer, another sometime resident of Cedar Rapids who was living in Paris at the time, “and I’m going to paint those damn cows and barns and barnyards and cornfields and little red school-houses and all those pinched faces and the women in their aprons and the men in the overalls and store suits and the look of a field or a street in the heat of summer or when it’s ten below and the snow piled six feet high. Damn it, isn’t that what Sinclair Lewis has done in his writing—in Main Street andBabbitt? Damn it, you can do it in painting too!”

That anyway is what Shirer remembered in his book 20th Century Journey. But deep down Wood respected the very things Sinclair Lewis and Mencken before him had held up to scorn. The artist had come to resent the fact that “Mencken belaboured my people as ‘corn-fed boobs and peasants’ in the Smart Set and the American Mercury.” A magazine article profiling Wood around 1935 quotes him saying that after his third trip to France he returned home “to see, like a revelation, my neighbours in Cedar Rapids, their clothes, their homes, the patterns on their tablecloths and curtains, the tools they use. I suddenly saw all this commonplace stuff as material for art. Wonderful material!”

As for the painting that made him famous, here are two responses he gave to speculation as to whether it was a caricature, and whether the couple were to be seen as man and wife, or father and daughter, or farmers or just small-town folks:

These are types of people I have known all my life. I tried to characterize them truthfully—to make them more like themselves than they were in actual life. They had their bad points, and I did not paint these under, but to me they were basically good and solid people. I had no intention of holding them up to ridicule.

All of this criticism would be good fun if it was made from some other angle. I do not claim the two people painted are farmers. All that I attempted to do was to paint a picture of a Gothic house and to depict the kind of people I fancied should live in that house. I hate to be misunderstood as I am a loyal Iowan and love my native state.

Rejecting bohemia

Wood was in good company when he said that to characterize his good and solid people he wanted to make them “more like themselves than they were in actual life”. Aristotle himself said something similar long ago. Greek drama was truer than written history, he claimed, because it represented general truths about history and humanity in a crystallized and clarified form. And it was exactly this condensed and crystallized presentation of general truths that soon made American Gothic a national icon.

But what was the art establishment to make of it all? Of a man who in 1935 defiantly produced a work with the title “Return from Bohemia” to emphasize his break with that squalid world? Not an alienated artist seeking to overthrow the family gods—and Puritanism especially—but a happy craftsman seeking to honor his ancestors. Not a revolutionary hoping to subvert “the system” but a man generally satisfied with the way things were. Not someone keen to spew political bile in all directions, but a man who loved his state and its people and the life he knew.

And all this at a time when every artist worth his salt was supposed to be moved more strongly by the emotion of hate than of love, to be driven by a compulsion to destroy the bourgeoisie and capitalism together, to overturn all settled values, and—not unreasonably on the eve of World War II—to show political militancy in the looming fight against fascism.

Unsurprisingly, the benignly populist character of Wood’s work in the 1930s (Biel describes some 1932 panels in a Cedar Rapids hotel as featuring “extraordinarily robust farmers, cows, chickens, pigs, geese, corn, melons” etc) drew fire from the Left for being inspired by the suspect sentiments of patriotism, nativism, and chauvinism. In 1935 Lewis Mumford detected in the work of Wood’s friend and regionalist ally Thomas Hart Benton “a reactionary aesthetics and politics that veered dangerously close to fascism”. Biel then writes that

However unfair his judgment of Wood’s work, Mumford astutely observed that in standing ‘for the corn-fed Middle West against the anemic East’ Wood had ‘become a National Symbol for the patrioteers.’ His regionalism, Mumford charged, posed no genuine alternative to nationalism, provincialism, and corporate capitalism.

But why on earth should it? Mumford’s list of evils included much that Wood admired, respected, and believed in—his native land, his home state of Iowa, and the thousands of farmers and small businessmen who despite the hardships of the Depression were battling on. In contrast, Mumford’s was a hate list of things to be destroyed by ideologically driven intellectuals who had lost belief.

The subjects Wood painted after he turned his back on Bohemia were the social types and traditions he most revered. The conflict between the destructive goals of a radicalised art establishment and the life-enhancing ideals of the artist was deep, and it may not be inappropriate to quote here from Jacques Barzun’s chapter “Art in the Vacuum of Belief” from his 1974 The Use and Abuse of Art. His text was originally a lecture given at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

We who make up the contemporary world are not lively—at times, one is tempted to say: not life-like. We are certainly not in love with life. We do not think life can be noble or even good. We take human life and our present view of mankind as equivalents and are not pleased.

When we speak of the human condition we mean something execrable, a prison sentence we must endure. We seldom find among men individuals to revere, and we have nothing but scorn for social types, which we now call roles, as if to emphasize their falseness.

The very word reverence has come to connote a benighted, ‘unrealistic’ frame of mind. The hero has disappeared from fiction, from history, and from life. Art is largely devoted to showing the contemptibility of the human animal or, by pointedly neglecting him, his irrelevance and superfluity.

From parody to nihilism

The contemptibility of a particular human animal—or if that’s too strong, then the comic irrelevance and superfluity of the rube, the bumpkin, the overalled workmen and pinafored farmwives of the “corn-fed Middle West”—would be universally assumed in the cultural role played by Wood’s painting after 1960. From that time on it would be continually exploited for both comic and commercial effect: one way or another the man with the fork and the sideways looking woman would be parodied to advertise food products and publicise television shows—most notably the Beverley Hillbillies—and it is this parodistic use we find once more in Fox Broadcasting’s 2005 poster for The Simple Life.

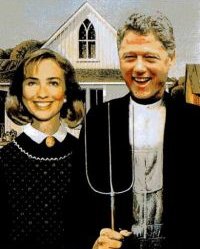

No doubt we shouldn’t be too solemn about it. Perhaps parody is the fate of all national icons. And no doubt the real-life persons who posed for Wood—his sister Nan and his dentist Byron McKeeby—should have learned to let go and not worry about the use or abuse of their personal images in his painting. Nor should we fail to recognise the ambiguity often displayed. Biel writes that “Instead of disparaging the ‘original’, American Gothic parodies frequently use it as a standard for evaluating contemporary society and politics. Sometimes the contemporary doesn’t measure up to what TV Guide called the ‘American Gothic hard core’ of national character.”

Yet there’s a remorseless destructiveness about the parodistic impulse that never knows when to stop. The more innocuous spoofs showed a couple like Bill and Hillary Clinton. But soon a libertine ‘let’s make it naked’ motive took over as the crux of the joke; nihilism beckoned; and after that it was downhill all the way. In 1966 Playboy grafted playmate Dolly Read’s shapely equipment onto a composite with Nan’s head. In 1967 a Johnny Carson routine showed Nan Wood stripped down with barely covered sagging breasts. Nan sued Carson and Look and Playboy magazines for nine million dollars, but got only a small settlement in the end. What she might have thought of a parody which replaced her with the image of a rich party girl best known for a video of herself copulating with a friend is anyone’s guess.

Yet there’s a remorseless destructiveness about the parodistic impulse that never knows when to stop. The more innocuous spoofs showed a couple like Bill and Hillary Clinton. But soon a libertine ‘let’s make it naked’ motive took over as the crux of the joke; nihilism beckoned; and after that it was downhill all the way. In 1966 Playboy grafted playmate Dolly Read’s shapely equipment onto a composite with Nan’s head. In 1967 a Johnny Carson routine showed Nan Wood stripped down with barely covered sagging breasts. Nan sued Carson and Look and Playboy magazines for nine million dollars, but got only a small settlement in the end. What she might have thought of a parody which replaced her with the image of a rich party girl best known for a video of herself copulating with a friend is anyone’s guess.

Nan Wood died in 1990. Steven Biel concludes his discussion of parody, and of the “desecration” of American Gothic in the poster for The Simple Life, with an observation that seems to me too complacent by half. After suggesting that in 2005 “Nan might have taken comfort in learning that fans of her brother’s painting again complained that the ads debased it”, he says that however wild or obscene they might be, “parodies fortify the ‘original’ as the embodiment of traditional American values. If it can be profaned, it must be sacred.”

If only! Professor Biel directs the History and Literature Program at Harvard and this statement smacks all too obviously of the ivory tower. His argument parallels Rochefoucauld’s observation that “hypocrisy is the homage vice pays to virtue”, Biel’s variation being that “parody is the homage vice pays to moral conduct and sincere belief.” But when virtue loses all her loveliness and sincere belief is thin on the ground, what then?

Is it really so trivial a matter, so meaningless, when Priapic Bill and Porno Paris are chosen to replace the austere quasi-religious iconic images of Nan Wood and Byron McKeeby? Or should we see in this displacement a symptom of more general trends, of a pervasive moral shift echoing Jacques Barzun’s gloomy assessment of how we live now—the scorn for traditional social types, the inclination to see reverence as a benighted and ‘unrealistic’ frame of mind, the ridicule of the heroic in a world given over to showing the contemptibility of the human animal?

Nemesis

If the human animal is contemptible then of course anything may be done to it—violation, mutilation, torture. In New York Magazine the film critic David Edelstein was meditating recently about some of the movies on show at the local multiplex. He described “not a bad little thriller” called Hostel “which spent a week as America’s top moneymaker.” According to Edelstein it shows a Slovakian village “where life appears to be a non-stop naked sauna party” and where the main thrills come from scenes showing an old man being eviscerated without anaesthetic.

A connoisseur of hack-‘em-ups who describes himself as a “horror maven”, Edelstein glances at Rob Zombie’s The Devil’s Rejects (in which a woman is run down by a semi and turned into heaps of innards), Greg McLean’s Wolf Creek (where a serial killer severs the heroine’s spinal cord and tells her “Now you’re just a head on a stick”), and closes with Gaspar Noé’s Irreversible. In this last film—which Edelstein tells us “many critics regard as deeply moral”—a pregnant woman is subjected to nine minutes of anal rape.

But the intriguing thing to me, in addition to the fact that all the victims are women, is that a New York reviewer for a well-known cultural publication should not only seek out this kind of show but enjoy it. At the end he confesses his own complicity, and signs off with what he regards as a joke: “I’ve described all this freak-show sensationalism with relish, enjoying—like these filmmakers—the prospect of titillating and shocking. Was it good for you too?”

Closely following Steven Biel, we began with the original painting by Grant Wood, American Gothic, a somewhat ambiguous image of Puritan integrity, austerity, and rural simplicity. We noted that the critical establishment at first embraced it as a weapon to be used to destroy traditional mid-Western religious values, in the manner of Mencken, Sinclair Lewis, et al, enthusiastically welcoming it as satire. We also saw how the painting later became used parodistically, until, in 2003, after raising the comic ante for decades, the complete inversion of its original moral significance was achieved by substituting Paris Hilton for Nan Wood.

By then the war against Puritan morals that had preoccupied American artists and writers and intellectuals from 1900 until 1960 was well and truly won. Playboy’s role was not insignificant: in the decades after 1960, the Hefnerization of much of middle America would be carried to a point where Las Vegas, not Cedar Rapids or Gopher Prairie, decisively sets the nation’s moral tone.

But anyone who may have thought that the war against Puritanism itself was over should now be having second thoughts. It was only the long and protracted internal conflict that had ended—the domestic war for the moral soul of America. Outside America, Puritanism—which might be better described as the whole religious universe of ethical conduct involving taboos, proscriptions, sexual scruples, and constraints on our more animal nature—was and is arming itself for a long and bitter fight.

The people in this outside world—including the Middle East—have seen and considered what the West has to offer, and they are unimpressed by a civilization that talks big about freedom, democracy, and living standards, but puts close-ups of Paris Hilton’s vagina on their children’s computers, and would like to put movies showing sadistic episodes of anal rape in their cinemas.

There is of course much more to be said about American Gothic, about the destruction of the moral world it represents, about the moral condition of western elites, and about the various motives driving Islamic fundamentalism. But until these simple facts about our own civilization’s dire moral condition are faced up to, it is pointless to imagine that Islam—or any other self-respecting religious culture—will be embracing “western values” any time soon.

An Australian writer living in Sydney, Roger Sandall is the author of The Culture Cult (2001), a study of romantic primitivism and its effects. His work has appeared in a number of places including Commentary, The American Interest, Encounter, The New Criterion, The American, Sight and Sound, Quadrant, Art International, The New Lugano Review, The Salisbury Review, Merkur, Mankind, Visual Anthropology, and Social Science and Modern Society.

An Australian writer living in Sydney, Roger Sandall is the author of The Culture Cult (2001), a study of romantic primitivism and its effects. His work has appeared in a number of places including Commentary, The American Interest, Encounter, The New Criterion, The American, Sight and Sound, Quadrant, Art International, The New Lugano Review, The Salisbury Review, Merkur, Mankind, Visual Anthropology, and Social Science and Modern Society.