Austen Henry Layard (1817-1894) is famous for discovering and excavating the palaces of the Assyrian kings. Undertaken between 1845 and 1851, this achievement made him celebrated as one of archaeology’s great pioneers, a man who brought to public notice a civilization few knew very much about before. The autobiographical materials presented here describe his earlier life in England and on the continent — and especially the years of his original journey eastward and his dramatic adventures among the Bakhtiari of the Zagros Mountains (1849-1842). The excerpts below are from Volumes I and II of his Autobiography and Letters, 1903, and from the 1894 edition of his Early Adventures in Persia, Susiana, and Babylonia.

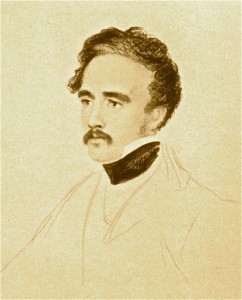

Born in England in 1817, Layard spent much of his boyhood in Florence. The family arrived in Italy in 1820. Young Layard’s formal schooling both in England and on the Continent was somewhat patchy, and it was his father who seems to have taught him most about art and literature. In Italy he played as a boy with the children of the English poet Walter Savage Landor.

Landor, literature, and The Arabian Nights

They were allowed to run wild, nearly barefooted, and in peasant’s dress, amongst the contadini (peasantry). Almost before they could lisp, Landor began to teach them ancient Greek. They were not sent to school, and the only time at which they were subjected to any kind of discipline was when his ungovernable temper was excited by something which they may have done to displease him, when he treated them very harshly. It is not surprising that this mode of bringing up his family should have led to much unhappiness. As it is well known, he left his wife soon after the time to which I am referring, and led a solitary and querulous life in England, until shortly before his death, when he returned to Florence, and was, I believe reconciled to her and his children.

Although my father had shunned personal intercourse with Landor, he greatly admired some of his writings and the vigour and purity of his English. He made me read the “Imaginary Conversations,” and learn passages from them. I took great delight in them; but they produced one effect which my father little contemplated: I imbibed from them those radical and democratic opinions which I sturdily professed even when a boy. The grand figure and powerful head of Walter Savage Landor, his sonorous voice, when he impressed upon me the beauty of the old Greek language, and the importance of its acquisition in order to speak and write good English, as he was often in the habit of doing, are still present to my memory. Many years after he addressed an Ode to me, which is published amongst his poetical works.

I profited little from my schooling at Signor Rellini’s Istituto, except that I obtained there that acquaintance with the Italian language which in after days was a source of so much pleasure, and of so much use to me. For such general knowledge as I acquired, and for the development of a taste for Literature and the Arts, I was indebted to my father. He was fond of reading, and possessed a small, but not ill-selected library. His favourite authors were those of the Elizabethan age. He taught me to appreciate and enjoy the plays of Shakespeare and Spenser’s “Faerie Queene.” Occasionally he read aloud to me passages from the plays of Ben Jonson, and other dramatists of the time, whose works he did not think it desirable to place in my childish hands. He admired the style of Hume, whose “History of England” I read with him. He was also fond of reciting the verses of “Peter Pindar” with me.

I had my own favourite books in which I was allowed freely to indulge. Before I had reached my thirteenth year, I had read all the novels of Walter Scott then published. But the work in which I took the greatest delight was the “Arabian Nights.” I was accustomed to spend hours stretched upon the floor, under a great gilded Florentine table, poring over this enchanting volume. My imagination became so much excited by it that I thought and dreamt of little else but “jins” and “ghouls” and fairies and lovely princesses, until I believed in their existence, and even fell in love with a real living damsel. I was deeply smitten with the pretty sister of one of my school-fellows. I fancied I had a rival in an English boy of my own age. We quarreled in consequence, and as we were both taking lessons of a fencing master, we determined to settle our differences in mortal combat with foils without the buttons. How we were prevented carrying out our bloody intentions I now forget.

My admiration for the “Arabian Nights” has never left me. I can read them even now with almost as much delight as I read them when a boy. They have had no little influence upon my life and career; for to them I attribute that love of travel and adventure which took me to the East, and led me to the discovery of the ruins of Nineveh. They give the truest, the most lively, and the most interesting picture of manners and customs which still existed amongst Turks, Persians and Arabs when I first mixed with them, but which are now fast passing away before

European civilization and encroachments. (Autobiography, v. I, 25-27)

Intellectual influences in London

Returning to the land of his birth, where his father died not long after, Layard joined his uncle’s law firm in London at the age of 16. His aunt kept a salon attended by distinguished artists and men of letters — one of them a friend of Goethe. Wordsworth was also frequently among the guests.

The person who exercised the greatest influence upon my future career was Mr Henry Crabb Robinson. I had made his acquaintance at Paris in August 1835, when on a tour in France and Switzerland with Mr Brockeden. With Stansfield, the painter, he joined company and travelled with us, took a friendly interest in me, and invited me to call upon him on my return to England at his chambers in the Temple, where he was in the habit of receiving many literary men of eminence. He had been the friend of Goethe and Wieland. He was so good a German scholar that the former said of him that “not only did he speak good German, but made good German.”

He was amongst the first Englishmen who cultivated the language, and made known to his countrymen the principal works of the most eminent German authors. His conversational powers were considerable. Having read and seen much, he possessed a large store of anecdote, and told his stories well. His experience of the world was large. He had lived during his youth in Germany and was a correspondent of the Times newspaper when Napoleon invaded that country. He used to narrate, with much effect, how he narrowly escaped falling into the hands of the French authorities, who would have shot him on account of the letters, which were very hostile to the Emperor…

It was Mr Robinson’s habit to have his friends to breakfast, especially on Sunday mornings. I received a general invitation to these breakfasts, of which I was delighted to avail myself. I soon became a welcome and almost a necessary guest on these occasions as I was useful in helping him to entertain his company. These meetings became a source of great pleasure and instruction to me. I frequently met at them some of the most eminent literary men of the day—amongst them Wordsworth, with whom Mr Robinson was very intimate. They had travelled together on the Continent, and he was accustomed to pay frequent visits to the poet at his residence at Rydal Mount. He was an ardent and enthusiastic admirer of Wordsworth’s poetry, which he read aloud with great animation and effect. He gave me a love for it which has not left me.

The poet himself, with his venerable and stately appearance, inspired me with the greatest respect and admiration. He was very kind to me, allowed me to talk to him freely about his works and on other subjects and even made at my suggestion a translation of one of Michael Angelo’s sonnets of which I was very fond. I have still in my possession the slip of paper upon which I wrote down this translation as he dictated it to me. It was afterwards published with some variations…

Mr Robinson was a Unitarian and what was then called “a philosophical Radical.” He introduced me to Mr Fox, the celebrated Unitarian preacher, who then had a chapel in the city which I frequently attended. The eloquence and powerful rhetoric of this remarkable man were a great attraction to me. His discourses and the conversation of my friend Mr Crabb Robinson rapidly undermined the religious opinions in which I had been brought up, and I soon became as independent in my religious as I had already become in my political opinions.

My uncle, who was supposed to look after me, and to exercise a moral control over me, was little pleased with either, as they both differed so entirely from his own. Being a Tory of the old school and a strict Churchman, he was bound to look upon them with feelings approaching to horror. He was afterwards wont to accuse Mr Crabb Robinson of having unsettled my mind, and of having encouraged in me pursuits and tastes entirely opposed to the serious study of the law, and which led me to abandon it for a life of travel and adventure. The charge was perhaps well founded. I have no reason to regret that it was so. (Autobiography, v. I, 54-56)

Italian society and politics

In the 1830s Layard made a number of visits to the Continent — travelling in Italy, mixing in Italian society, and befriending Cavour and the Carbonari. He particularly remembered the Contessa Galateri, ‘well-known in Turin Society’ for her beauty and accomplishments.

Although the education of women was, up to a very recent period, sorely neglected in Italy, and their intellects had been as little attended to as their morals, an accomplished and highly-cultivated Italian lady—and I have known many such—has always appeared to me the most perfect type of her sex. The Galateris were acquainted with, or allied to, the principal families in Piedmont. During our excursion (i.e., in 1835-36) we spent much of our time in country houses, and in the most agreeable society. We were a merry party, committing all manner of extravagances, singing, dancing, serenading by night on the water, and making expeditions in the hills.

We spent a very pleasant week in rambling about the mountains, and then paid visits to country houses, amongst them to the villa of the Cavours, where Camille de Cavour was then staying. Italian countryhouse life, with its freedom and complete absence of conventionality, has always had a great charm for me. The society was delightful. We everywhere met handsome and accomplished women. We had concerts, and I played more than once on the flute in Masses performed at church ceremonies…

During my visit to Turin I had made the acquaintance of several young men who were active members of the Liberal party, and were consequently suspected by the Government, against whose policy they were in open opposition… I believe that Camille de Cavour then took no direct share in it, although he had been persecuted and imprisoned on account of his Liberal opinions. I never saw him at any of the secret meetings at which I was present.

One of the young men whose acquaintance I had thus formed, a certain Signor Soffietti, who was a zealous member of one of these secret associations, had given me a letter and some papers to be delivered to a Piedmontese political refugee living at Lyons. I stopped there a couple of days to see him. There were many other fugitives from Piedmont and other parts of the Peninsula living in the city, who were in correspondence with the promoters of the insurrectionary movements in Italy, and who were known as “Carbonari,” the name then given to the members of the secret revolutionary societies which were conspiring against the Austrian rule in Italy.

Their agents had on many occasions been guilty of acts of bloody vengeance upon the oppressors of their country, which had brought them to the scaffold. I was presented, as a friend of Italian liberty, to several of these youthful conspirators at a secret meeting to which I was invited, having been previously warned that such meetings were strictly prohibited by the French authorities, and that, if we were discovered, we should all pass into the hands of the police, and probably find ourselves in prison. My enthusiasm in the cause induced me, however, to run the risk, although I remember being well pleased when I found myself safe back in my hotel.

Although these young men were as conspirators odious to, and persecuted by, all Continental Governments, they were, for the most part, honest and sincere patriots in the truest sense of the word—ready to make every sacrifice, even that of life, for the freedom and independence of their country, and for what they believed to be its welfare. They lived in the greatest poverty; had renounced all worldly advantages; and had, in numerous instances, even cast off the dearest of ties—those of the family—when their relations disapproved, or feared to be compromised by, their proceedings… To their indomitable courage and perseverance, and to their readiness to sacrifice even life for their country, Italy owes her freedom and her regeneration. I little thought that it was under the lead of the young man whose acquaintance I had made at Turin that this great work was to be accomplished. (Autobiography, v. I, 78-92)

Travelling east — Montenegro

Wearying of the routine in his uncle’s London law office, where he was employed copying documents, Layard (22) joined Edward Ledwich Mitford (32) on a journey to Turkey and the Middle East. Ledwich was to continue overland to India. For Layard it was the beginning of his association with Mesopotamia and the long-buried remains of ancient Nineveh.

It chanced that Mr Edward Ledwich Mitford, a young Englishman who had been connected with a mercantile house at Mogador in Morocco, and who had made some interesting excursions through little known parts of that dangerous country, desired to establish himself in Ceylon as a coffee-planter. Like myself, he wished to leave England as soon as possible; but being of an adventurous disposition, and dreading the sea, he had formed a plan for going to Ceylon by land through Europe, Central Asia, and India. He proposed to me that we should perform the journey together.

I was much struck by this grand idea. It coincided entirely with my love of travel and adventure, and, if carried out, would enable me to visit many of the most interesting parts of the East, and to realize the dreams that had haunted me from my childhood, when I had spent so many happy hours over the “Arabian Nights.” I willingly accepted his proposal. And it was agreed that we should leave England without delay. (Autobiography, v. I, 102)

All our preparations having been at length completed, I bade farewell to my mother, who had come to London to see the last of me, and on the 10th July (1839) we left London by a steamer for Ostend. As we passed down the Thames I laboured under various emotions. I had an unknown future before me. My chances of success in the new career I had chosen for myself were doubtful. My plans were, after all, vague and somewhat wild. If I failed in the object of my journey, and the means of supporting myself were wanting, what was to become of me?

But notwithstanding these doubts and considerations, I experienced a happy sensation of relief at leaving England and abandoning a pursuit which was odious to me. I was now independent, and no more exposed to the vexatious interference and control to which I had hitherto been subjected, and greatly resented. I was of sanguine and hopeful temperament; I had robust health and much energy, and courage and determination enough to grapple with any dangers and difficulties that I might have to encounter. I was consequently in no way dismayed by the prospect before me, but was fully prepared for the consequences, whatever they might be, of the step that I had taken.

In leaving England I had nothing to regret except the separation from my mother. Had I remained, I should in all probability have passed through life in the obscure position of a respectable lawyer, unless some opening, which could not have been foreseen, might have enabled me to distinguish myself in some other career. (Autobiography, v. I, 108-109)

A visit to the capital city of Cetinje. At Cetinje Layard stayed with the Vladika, the Prince-Bishop of Montenegro who was head of government. The Vladika’s reform program, intended to introduce his subjects to Western Civilization, appeared to be faltering.

We remained several days at Cetinje, passing most of our time with the Vladika, with whom I had much conversation as to the condition of his people, and as to his attempts to civilise and educate them. He had procured a billiard-table from Trieste, and was fond of the game. We played several times together. On one occasion whilst we were so engaged, a loud noise of shouting and of firing of guns was heard from without. It proceeded from a party of Montenegrin warriors who had returned from a successful raid in the Turkish territory of Scutari (Albania), and, accompanied by a crowd of idlers, were making a triumphal entry into the village.

They carried in a cloth, held up between them, several heads which they had severed from the bodies of their victims. Amongst these were those apparently of mere children. Covered with gore, they were a hideous and ghastly spectacle. They were duly deposited at the feet of the Prince and then added to those which were displayed on the round tower near the convent.

I could not conceal from the Vladika my disgust at what I had witnessed, and expressed my astonishment that, with the desire he had expressed to me of civilising his people, he permitted them to commit acts so revolting to humanity and so much opposed to the feelings and habits of all Christian nations. He replied that he must readily admit that the practice of cutting off and exposing the heads of the slain was shocking and barbarous, but it was an ancient custom of the Montenegrins in their struggles with the Turks, the secular and bloodthirsty enemies of their race and faith, and who also practiced the same loathsome habit.

He was compelled, he went on to explain to me, to tolerate, if not to countenance, this barbarous practice which he condemned on every account, because it was necessary to maintain the warlike spirit of his people… They were few in number compared with their enemy, and unless they were always prepared to defend their mountain strongholds, they would soon be conquered and exterminated… There was nothing he dreaded more, he said, than a lengthened peace, for if the Montenegrins were once to sleep with a sense of security, and were no longer in a state of continual warfare, they would soon be conquered.

It was for these reasons, he declared, that it would be unwise on his part to make any attempt for the present to put a stop to a practice which encouraged his people in their hatred to the Turks, and in their determination to perish rather than allow the Moslems to obtain a footing in their mountains. (Autobiography, v. I, 132-133)

Law and order in Montenegro. A poet and a man committed to reform, Montenegro’s leader discussed with Layard his plans for the Balkan nation. He was busily building schools, and planned to appoint Serbians to staff and manage them.

The Vladika had introduced, for immediate purposes, some new laws, but he was then occupied in framing a new code better adapted to improve the civilisation of his subjects. He explained to me how hitherto human life had been too lightly esteemed amongst the Montenegrins. Injuries and insult were readily avenged by the death of the offender, and quarrels were of frequent occurrence; murders were constantly committed.

In the past the murderer had been only punished by a fine in money paid to the family of the victim; now he was punished by death, the criminal being taken to his own village, and there shot by his own kith and kin. Women when convicted were stoned to death also in their native villages. He made to me the almost incredible statement that previous to the enactment of this new law the feuds ending fatally between individuals and between villages were so frequent, that there were years in which as many as 600 deaths occurred, and that there were never less than 300. For the previous two years the average was 400, and in each case the murderer had been condemned and executed. (The estimated population of Montenegro at the time was around 100,000. RS)

Punishments were now inflicted for robbery, theft, and other crimes; this formerly was rarely the case. The result was that public order and security had been, His Eminence maintained, established to a great extent in his dominions, although he did not deny that there was yet much to be done. He was, however, engaged in framing a complete code of laws, which he hoped would have the effect of placing Montenegro on an equality in these respects with European states. But in order to accomplish this fully, it was necessary to educate its population, and with this object he was engaged in building schoolrooms in different parts of the principality, which would be opened within a year, and placed under the direction of schoolmasters from Servia, as there were no Montenegrins yet capable of undertaking their management.

He declared that his subjects, although ignorant and occupied with little else but war, looked with anxiety and interest to the successful result of his efforts to introduce civilisation amongst them, and that he had every hope that in a few years a great change for the better would have taken place in their habits and condition. He greatly extolled the independence of character and love of liberty of his people. The Austrians and Russians, he declared, were slaves, the Montenegrins free men who would not tolerate arbitrary or despotic rule. They were all equal… (Autobiography, v. I, 134-135)

Character and conduct of the Montenegrins

I was much struck with the superior intelligence and liberal views of the Vladika. It was certainly remarkable that so young a man, brought up in the prejudices of a wild and barbarous people — hostile to all change and improvement, excessively tenacious of their ancient national habits and traditions, and cut off from the rest of mankind by implacable enemies and almost impassable mountains — should have developed the qualities which he possessed. I could not but admit that he deserved the reputation which he enjoyed amongst those who had known him during his travels.

At the time of my visit to him the Montenegrins had the character of being a tribe of robbers, marauders, and assassins, brave and ready to die in defence of the freedom which they had maintained in their mountain fastnesses, but bloodthirsty and treacherous. They were not altogether undeserving of their reputation. Their constant and frequently unprovoked raids upon their neighbours’ territories for the purpose of plunder, or to gratify their religious fanaticism by slaughtering the infidels, were accompanied by acts of ferocious cruelty, which had long rendered the name of Montenegrin odious and dreaded by Mussulmans and Christians alike.

Secure in their inaccessible mountains, excellent marksmen, awaiting their enemies behind rocks, brave and ready to die rather than lose their freedom, they were able to resist for generations the numerous attempts made by the Ottomans and Austrians to punish and subdue them. When, as in more than one instance, the Turks were obtaining advantages over them which might have led to their subjection, they received the powerful support of Russia, who for political objects of her own, and out of sympathy for people of her own race and faith, was always ready to step in for their defence, and to menace the Porte with her displeasure if it ventured to take advantage of the successes which its troops might have achieved over the mountaineers.

The Mussulman inhabitants of the districts adjacent to the Black Mountain were consequently compelled to submit to the depredations and excesses of their restless and barbarous neighbours. Their villages were burnt, their women and children barbarously mutilated and slain, and a harvest of heads periodically carried off as trophies by their invaders. (Autobiography, v. I, 136-137)

In the vicinity of Tarsus, on the Mediterrranean. After calling at Constantinople, and crossing Anatolia, the travelers descended from the Taurus Mountains to the Mediterranean coast of Turkey at Selefkeh, on their way to Aleppo and Jerusalem.

Our path was carried through a valley along the bank of the Calycadnus, a broad and clear stream, now called by the natives the Ghiok Su — “blue water.” The mountains on either side were thickly wooded. As the night came on we saw on all sides the fires of an encampment of the Ourouks. Although Iapandé, which we reached after dark, had only three or four houses, it contained the travellers’ oda (guest-house), which was rarely, if ever, absent from a Turkish village. There we installed ourselves, and were hospitably supplied with the best supper that the village could produce.

The evening meal, served to us by the kindly villagers in the room reserved for their guests, usually consisted of a very palatable soup, small lumps of boiled mutton, an omelet, a pilaf, and large flat cakes of unleavened bread. Sometimes, however, there was no meat to be obtained, as the inhabitants themselves did not often enjoy what was to them a luxury. I need scarcely say that we were never given wine or any spirituous liquor in a Mussulman house, whilst strong raki was usually presented to us by Christians, nor had we any provision of such things with us. We drank nothing but water and the usual sour milk which is found in most Turkish cottages in the interior. Fresh milk is considered unwholesome by all Easterns, and is rarely, if ever, drunk.

According to the custom of the country, nothing is paid for food, which is furnished by the community gratuitously to a stranger, but it was our invariable habit to give a small sum for the Odabashi, or owner, or man in charge of the guest-house. Sometimes we were, in addition, supplied with coverlets, which now that the weather was cold — we were in the month of November — were very acceptable, and we slept on the mattresses covered with European chintz, which formed a kind of low divan round the room, the floor of which was covered with mats. The principal drawback upon these otherwise pleasant nights’ quarters were the fleas and other vermin. We were, however, free from their attacks in our “Levinge” sheets, and they diminished and finally disappeared as the cold weather came on.

Before the supper was brought in upon a polished metal tray, the chief men of the village would sit with us. They retired when we ate and returned after we had finished our meal, leaving us when we desired to retire to rest, which we did very early, as we were generally fatigued with our long day’s ride. I still look back to those evenings pleasantly spent in conversing with these simple and kindly people, and in obtaining information as to their country habits, and customs. I thus learnt to appreciate the many virtues and excellent qualities of the pure Turkish race, and to form that high opinion which I have never had reason to change of the character of the true Osmanlu, before he is corrupted by the temptations and vices of official life and of power and by intercourse with Europeans and the Europeanised Turks of the capital. (Autobiography, v. I, 192-193)

After arriving at Selefkeh (ancient Cilician Seleucia) and crossing the Calycadnus by a Greek or Roman bridge, they explored the nearby country.

We wandered about during the remainder of the day in search of ruins. We found the remains of two temples with many columns of white marble still standing, and of a theatre with porticoes and adjacent edifices; architectural ornaments of exquisite delicacy of work and beauty of design; numerous capitals and shafts of columns of a florid Corinthian order scattered about the town, and built into the walls of houses — I counted no less than fifteen of the latter in the yard of our khan (guest-house) — an extensive excavation in the rock below the castle, about 150 feet long, 75 broad, and 40 deep, with arches of solid masonry round the sides, the bottom reached by stairs formed of large blocks of stone; many excavated tombs in the surrounding rocks, with the troughs similar to those we had met with in such abundance in Phrygia; sarcophagi used as reservoirs for fountains, with remains of inscriptions, some of the Christian era; and on all sides traces and foundations of ancient buildings.

About two miles from Selefkeh, in a valley wooded with larch, I found an aqueduct of which fifteen arches in two tiers, nine in the lower and six in the upper, still remained. The view which it commanded was of marvelous Southern beauty — the fine old castle and the ruins of the ancient city backed by the lofty serrated range of Taurus, the small plain with its luxuriant vegetation, beyond the blue Mediterranean, in the extreme distance Cyprus faintly visible. Scenery of this exquisite loveliness abounds along the Karamanian coast which we had reached.

After passing two hamlets (beyond Selefkeh on the way to Tarsus) we came upon the remains of the Roman town of Poccile Petra. They were of considerable extent, and almost concealed by dwarf oaks and myrtles in full flower. The scene was altogether one of surpassing beauty. The ruins occupied a small valley opening upon the sea. Amongst them rose the remains of more than one temple, a triumphal arch, with an inscription stating that the town had been founded by one Flurianus, in the reign of Emperor Valentinian. A beautiful structure of white marble, with a vaulted ceiling and entirely open on one side, stood at a short distance from the town, probably a tomb, as around it were sarcophagi and troughs cut in the rock, from which the lids had been forcibly removed, many of them bearing the traces of inscriptions in Greek characters.

As we continued along the coast we passed many ruins, some apparently of small temples, others of tombs and the remains of buildings. During the day we had seen in the distance to the east the mountains of Syria rising majestically from the sea. As we forced our way through myrtle and olive bushes and marshy ground, game of many descriptions rose in all directions — francolins (the black partridge), partridges, quails, snipe, ducks, widgeon, and various kinds of water-fowl.

The sun went down in all its glory, lighting up this beautiful coast and the distant mountains of Taurus and Syria, and turning the blue Mediterranean into a sheet of purple and gold. In the distance, close to the coast, rose the picturesque castle of Korgos, built upon a small island. I never saw anything more lovely, nor had I ever enjoyed so many delightful sensations as our day’s ride afforded me. I have never forgotten it. The beauty of the distant mountains, the richness of the vegetation, the utter loneliness and desolation of the country, the wonderful remains of ancient civilization, the graceful elegance of the monuments, the picturesque aspect of the ruins, the blue motionless sea reflecting every object, with here and there a white sail, all combined to form a scene which it would be difficult to equal and impossible to surpass. (Autobiography, v. I, 197-200)

Jerusalem and Petra

Although the British consul in Jerusalem strongly warned against it, because of the menace of marauding Bedouin, Layard was determined to visit Petra. The following narrative combines material from his Autobiography and Letters with excerpts from the more complete account provided in the Early Adventures.

I had determined to visit Petra and some of the more important sites and ruins on the other side of Jordan. The authority of the Egyptian Government had not been established to the east of that river… The country was consequently unsafe for travelers, and the British Consul, and such Europeans as I had met in Jerusalem, declared that I could not attempt to pass through it without running the greatest risk. Parties of Bedouin marauders were said to be scouring the plains, and the scanty Arab population of Moab and Petra was said to be treacherous, fanatical, and hostile to Europeans.

Wherever I might go I should find myself in the midst of robbers and assassins. It would be impossible to reach Petra without either engaging the services of an Arab Sheikh of local influence and of power, who could conduct me in safety through the tribes on my route, for which I should have to pay a handsome backshish, or without a large military escort, which the Egyptian authorities would be unable to afford me…

The difficulties and dangers of this expedition which I meditated appeared to be so great, and the warnings of the Consul and others were so serious and urgent, that my companion, Mr Mitford, considered it prudent not to run them. I was determined, however, not to be baffled. We agreed to part for the time, and to meet again at Aleppo, to which place he would proceed leisurely by way of Damascus, after prolonging for some time his stay in Jerusalem. I was to make the best of my way to that place through the desert. (Autobiography, v. I, 279-281)

The journey described in Layard’s Early Adventures was an unending succession of fraught encounters with Bedouin tribesmen, one of them taking place soon after he reached Petra. Layard was accompanied by a personal servant, Antonio, and two youthful Arabs, Awad and Musa.

On the following morning we entered the Wady Musa, or Valley of Moses, and in an hour and a half I found myself amid the ruins of Petra. Everywhere around me were remains of ancient buildings of all descriptions, whilst in the high rocks which formed the boundaries of the valley were innumerable excavated dwellings and tombs. As I had intended to visit the ruins leisurely, I did not stop to examine them but, passing through them on my camel, ascended to a spacious rock-cut tomb, in front of which was a small platform covered with grass. There I made up my mind to pitch my tent.

I dismounted and spread my carpet. I had scarcely done so when a swarm of half-clad Arabs, with disheveled locks and savage looks, issued from the excavated chambers and gathered round me. I asked for some bread and milk, which were brought to me, and Antonio prepared my breakfast, the Arabs watching all our movements. Their appearance was far from reassuring, and my guides were evidently anxious as to their intentions. They were known to be treacherous and bloodthirsty, and a traveler had rarely, if ever, ventured among them without the protection of some powerful chief or without a sufficient guard.

They remained standing round me in silence, until they perceived that I was about to rise from my carpet with the object of visiting the ruins in the valley. Then one of them advanced and demanded of me in the name of the tribe a considerable sum of money, which, he said, was due to it from all travelers who entered its territory. I refused to submit to the exaction, alleging that I was under the protection of Sheikh Abu-Dhaouk. I was ready, I added, to pay for any provisions that might be furnished to me, or for any service of which I might be in need.

This answer gave rise to loud outcries on the part of the assembled Arabs. They began by abusing my two guides, whom they accused of having conducted me to Wady Musa without having first obtained the permission of their sheikh. A violent altercation ensued, which nearly led to bloodshed, as swords were drawn on both sides. An attempt was made to seize my effects, and I was told that I should not be allowed to leave the place until I had paid the sum demanded of me. As I still absolutely refused to do so, one, more bold and insolent than the rest, advanced towards me with his drawn sword, which he flourished in my face. I raised my gun, determined to sell my life dearly if there was an intention to murder me. Another Arab suddenly possessed himself of Musa’s gun, which he had imprudently laid on the ground whilst unloading camels….

In the first place, I thought it right to resist this attempt to blackmail a traveller; and, in the second, had I been even disposed to yield, I had not enough money with me to give what was asked. I therefore directed Musa and Awad to reload the camels and to prepare to accompany me. Seeing that I was determined to carry out my intention of visiting the ruins without their permission, the Arabs formed a circle round me, threatening to prevent me from doing so by force, gesticulating and screeching at the top of their voices. With their ferocious countenances, their flashing eyes and white teeth set in faces blackened by sun and dirt, and their naked limbs exposed by their short shirts and tattered Arab cloaks, they had the appearance of desperate cut-throats ready for any deed of violence. (Early Adventures, 14-17)

At this juncture the Sheikh of Wady Musa made his appearance.

Having somewhat calmed his excited tribesmen and obtained silence, the Sheikh of Wady Musa inquired into the cause of the disturbance. Having been told it, he announced that he had a right, as chief of the tribe in whose territory the ruins were situated, to the sum originally demanded, and that unless I paid it he would not permit me to visit them. He was a truculent and insolent fellow, tall, and with a very savage countenance; rather better dressed than his followers, and armed with a long gun and pistols, whilst they only carried swords and spears.

I repeated my resolution not to submit to this imposition, and warned him that if any injury befell me he would be held personally responsible by Ibrahim Pasha, who had given ample proof that he could punish those who defied his authority. Abu-Dhaouk, moreover, I said, was a hostage for my safety. I then rose from my carpet and, directing Awad and Musa to follow me with the camels, which they were loading, prepared to begin my examination of the ruins.

The sheikh, seeing that I was not to be intimidated, and fearing the consequences should any violence be offered to me or to my guides which might lead to a blood-feud between his tribe and that of Abu-Dhaouk, ordered his men to stand back, and I went on my way without further interference. As I descended into the valley he called out to me by way of benediction, ‘As a dog you came, as a dog you go away.’ I gave him the usual Arab salutation in return, and threw him a piece of money in payment for the bread and milk which had been brought to me on my arrival. This return for hospitality would have been resented as an insult by a true Bedouin, but he picked up the silver coin, and as I left I saw him crouching down on his hams surrounded by his Arabs, evidently discussing the manner in which I ought to be dealt with.

Awad and Musa were a good deal alarmed at my reception, and feared that the sheikh and his followers would find some means of avenging themselves upon me. They urged me, therefore, to leave the valley as soon as possible. But I was convinced that, notwithstanding the chief’s threats, he would not venture to rob or injure me… I was determined, as I had come so far to visit the ruins of Petra, to examine its principal monuments leisurely, and I spent the whole day in doing so. I was not molested, but I observed Arabs watching all my movements…

The scenery of Petra made a deep impression upon me, from its extreme desolation and its savage character. The rocks of friable limestone, worn by the weather into forms of endless variety some of which could scarcely be distinguished from the remains of ancient buildings; the solitary columns rising here and there amidst the shapeless heaps of masonry; the gigantic flights of steps, cut in the rocks, leading to the tombs; the absence of all vegetation to relieve the solemn monotony of the brown barren soil; the mountains rising abruptly on all sides; the silence and solitude, scarcely disturbed by the wild Arab lurking among the fragments of pediments, fallen cornices and architraves which encumber the narrow valley, render the ruins of Petra unlike those of any other ancient city in the world.

The most striking feature at Petra is the immense number of excavations in the mountain-sides. It is astonishing that a people should, with infinite labour, have carved the living rock into temples, theatres, public and private buildings, and tombs, and have thus constructed a city on the borders of the desert, in a waterless, inhospitable region, destitute of all that is necessary for the sustenance of man — a fit dwelling-place for the wild and savage robber tribes than now seek shelter in its remains. (Early Adventures, 17-19)

Though he survived the journey south of the Dead Sea, and made it back to Damascus, Layard admits in his Autobiography that the venture was foolhardy. He was in fact lucky to come out alive.

Consul Young and my other European acquaintances considered me guilty of unjustifiable foolhardiness in undertaking so dangerous a journey under such conditions, and foretold that all manner of mishaps were certain to befall me, the least of which would be that I should be stripped to the skin and have to find the way back to Jerusalem naked and barefooted.

They were right, and had I had a little experience of Arabs and of travelling in the desert, I should have listened to their warning. But I had romantic ideas about Bedouin hospitality, and believed that if I trusted to it, and placed myself unreservedly in the power of the Bedouin tribes, trusting to their respect for their guests, I should incur no danger. I did not know that the Arab tribes who inhabit the country to the south and east of the Dead Sea differ much from the Bedouins of the desert, of whom I had read in the travels of Burkhardt, and that they fully deserved the evil reputation which they had acquired at Jerusalem. (Autobiography, v. I, 282)

From Mosul to Baghdad

Layard and Mitford crossed on horseback from Aleppo to Mosul, then travelled by raft down the Tigris to Baghdad. En route, Layard’s imagination was fired by scenes along the way — his mind turning romantically back to The Arabian Nights.

The Tigris was now swollen by the melting of the snow in the great range of mountains in which it takes its source. During the usual floods of spring, which generally last for about two months, the inhabitants of the banks use its rapid stream for the conveyance of their merchandise and other produce by raft to Baghdad. These rafts, which are frequently of large size, are made of the inflated skins of sheep and goats, which are fastened together by willow twigs. Upon these are laid reeds and planks, on which the goods to be conveyed are piled. They are guided by one or two men, and, when large, by more with paddles. When they arrive at their destination they are, after being unladen, broken up. The wood finds a ready sale — the skins are brought back for further use.

When travelers use these rafts, as they frequently do, they have wooden bedsteads placed upon them, which, formed into a kind of hut by being arched over with canes covered with felt, afford a pleasant shelter from the sun during the day, and from the cold air during the night. We determined to avail ourselves of this comfortable means of conveyance to Baghdad, and to sell our horses. I sold my mare — although greatly out of condition after her long journey — for about the same price as I had paid for her…

Our raft was about twelve feet long and eight feet wide, and was made up of fifty skins, the price of a raft being regulated according to their number. On the planks and reeds which were laid across them were placed two bedsteads such as I have described. One boatman only was required to guide our craft. He seated himself on his hams on a board, with paddle in hand, which he used to keep the raft in the centre of the stream, or to impel it to the bank in case we desired to land. We shot rapidly down the current in the middle of the river, which had overflowed its banks to a considerable distance, and were soon out of sight of Mosul.

Late in the afternoon we perceived the great conical mound of Nimroud, which I had before seen from Hammun Ali, rising in the distance. We were carried over the remains of a very ancient dam, probably of Assyrian times, over which the river dashed in foaming waves. Our pilot skillfully guided his raft, which bent and heaved as if it were about to break up and deposit us in the stream through the perilous rapids. We then glided swiftly and calmly onwards, the huge Assyrian mounds gradually disappearing in the evening twilight. During the night we continued our voyage, our boatman apparently not sleeping, and in the morning when we woke, found ourselves floating past the barren, precipitous Hamrin Hills, through the lower ridge of which, soon losing itself in the desert, the Tigris forces its way. We swept by many ancient mounds and ruins, with the walls and foundations of buildings exposed where the banks had been washed away by the impetuous stream.

We reached the ruin of Tekrit, inhabited by Arabs, in the afternoon. Here we had to wait for about an hour to change our boatman, and to refill the skins of the raft, from which the air had escaped. We then resumed our voyage, and the next day, having floated onward all night, came in sight, about noon, of the first grove of palms on the Tigris, and the first that I had ever seen. Amongst these tall and graceful trees, and beneath their shade, were clusters of orange, citron, and pomegranate trees, in the full blossom of spring. A gentle breeze wafted a delicious odour over the river, with the cooing of innumerable turtle-doves. The creaking of the water-wheels, worked by oxen, and the cries of the Arabs on the banks added life and animation to the scene. I thought that I had never seen anything so truly beautiful, and all my “Arabian Nights’” dreams were almost more than realized.

I know of no more enchanting and enjoyable mode of travelling than that of floating leisurely down the Tigris on a raft, landing ever and anon to examine some ruin of the Assyrian or early Arabian time, to shoot game, which abounds in endless variety on its banks, or to cook our daily food. It is a perfect condition of gentle idleness and repose, especially in the spring. The weather was delightful — the days not too hot, the nights balmy and still. We were warned that there were Arabs on the banks who would rob us and plunder us of our raft if we ventured to land, or would fire upon us if we refused to approach the shore. But we saw none of them. (Autobiography, v. I, 322-325)

Baghdad 1840

There was a reason why they were not attacked — a ferocious penalty for robbery had until recently been imposed in Baghdad, although Layard was not to find this out until later. After they had arrived in the city a small house was put at the travellers’ disposal by the Political Resident or Agent of the East India Company at Baghdad, Colonel Taylor, a scholarly man who had previously seen service in the Indian army.

In the society of Englishmen and native gentlemen my time in Baghdad passed most agreeably and too quickly. I still look back to those days with pleasure and regret. Nor was it spent unprofitably. Upon the advice of Colonel Taylor I engaged a moonshee (writer/secretary) to give me lessons in Persian, and I was able to acquire sufficient of that language to be of great assistance in my subsequent wanderings in Persia. Colonel Taylor himself was a most accomplished and profound Eastern scholar, with a rare acquaintance with Arabic literature, and abounding in general knowledge.

He possessed a choice and valuable collection of Arabic and Persian manuscripts, and especially of the works of the early Arabian geographers, which threw light upon the ancient geography and history of Babylonia and Assyria and the regions subsequently ruled by the Caliphs… Colonel Taylor was as modest and retiring as he was learned and accomplished. He published little or nothing, and when he died in England his great and rare knowledge died with him.

The residency was a vast building, divided, as I have said, into two parts, the Divan Khaneh, and the enderun or harem. The Colonel entertained his guests in the Divan Khaneh, the rooms of which were handsome and spacious. His table was spread for every meal with the most profuse hospitality, and there were places for all the English in Baghdad, who were welcome to it whenever they thought fit to dine or breakfast with him and his family. The service was performed by a crowd of Arabian and Indian servants in their native costumes, moving noiselessly about with naked feet, and attending promptly and well to the wants of the guests.

At breakfast, the Indian non-commissioned officer in command of the guard of Sepoys always appeared, and after drawing himself up in military fashion and giving the prescribed salute, announced in Hindustani that “all was well.” When the meal was ended, an army of attendants brought in kalleons, the Persian hookah, or waterpipe, of silver and exquisite enamel, one for each person at the table, except, of course, the ladies. (Autobiography, v. I, 339-340)

The condition of Baghdad. Layard describes the misgovernment of Baghdad under the Sultanate, and visits a typical local Governor, or Pasha, of the time. He contrasts what he knows about the city under the Caliphate and its appearance under Ottoman rule.

Much as I had been struck with the appearance of Baghdad as we had floated to it through groves of palms and orange and citron trees, with the gilded domes of Kausiman, and the many cupolas covered with bright enameled tiles of the city itself rising above them and glittering in the sun, so much the more was I disappointed when I found myself in its narrow and dirty streets. More than one quarter was nothing but a heap of ruins without inhabitants.

Even in the part occupied by the better class of the population, the houses, some of considerable size, were for the most part falling into decay. The exteriors, like those of the houses of Damascus, were of sun-dried bricks without ornament or window. It was only after passing through a long, tortuous, vaulted entrance that the extent of the interior and the beauty of its painted and sculptured decorations, fast falling into decay and perishing, were perceived. The streets had consequently a mean and poverty-stricken appearance, which was not altogether warranted by the condition of the inhabitants.

The mosques, with their beautiful domes and their elegant minarets, were falling to ruins. No attempts were made to repair and maintain them. The ample revenue which had once been applied to these purposes, and came from the bequests of pious persons, and from other sources, had now passed into the hands of the Turkish Government, and no part of them was applied to the object for which they had been intended. Of the great edifices, the palaces, the colleges, the caravanserais, the baths, and other public edifices which had once adorned Baghdad, scarcely anything remained… The city of the Caliphs had become a desolation and a waste.

The only part of Baghdad which retained any animation and life was the bazaar; long, gloomy, narrow streets, covered with awnings of matting to keep out the rays of the sun, and lined on either side with shops or booths, with raised platforms in front, on which were seated cross-legged their owners, patiently waiting, smoking their narguilés (hookahs) and sipping their coffee, until a customer might ask for their wares. At constant intervals were the coffee-shops, within and in front of which sat on low stools a mingled crowd of Mussulmans and Christians, inhabitants of the town and Arabs from the country, some playing at draughts or chess, or at a game in which beans were moved backwards and forwards in cups cut into a board, and passers-by occasionally stopping to offer advice and to suggest a move.

These bazaars were always crowded from daybreak to nightfall, after which they were entirely deserted except by solitary watchmen and the usual street dog. I often passed through them in the night, and was always impressed by their gloomy, weird, and silent aspect after the busy and noisy scene that I had witnessed during the day, when Arabs, Kurds, Persians, Indians, and men of every colour and clime hustled each other, and the place resounded with their discordant cries. Then, a horseman could with difficulty make his way through the crowd; and the mounted officers of the Pasha, and the Bedouin on his mare, with his long spear tufted with ostrich feathers, were assailed with loud or muttered curses as they attempted to force their way through the dense mass of human beings. (Autobiography, v. I, 342-343)

New Turkish regime no better. Under the old Turkish system, Pashas or Governors were “almost independent of any control.” They sometimes made improvements, but their discipline was harsh. In 1840 things were changing. Now the worst kind of officials were being sent from Constantinople to govern the provinces — men driven by no higher motive than personal gain from extortion and bribery.

The last of the semi-independent Governors in Baghdad had been one Daoud Pasha, a man of energy, and of sufficient intelligence to take some interest in the prosperity of the province. He had introduced the cultivation of sugar, and had found other means of giving employment to the population. By measures of great severity and cruelty he maintained order in his Pashalic. In his time robbers were rare, the Bedouins were kept in check, and the roads were secure; he was the last who had inflicted upon evil-doers the horrible punishment of impalement.

He was in the habit of placing them on the stakes at the two ends of the bridge of boats across the river, and on either side of it, as a warning to those who visited the city and had to pass between them. Dr Ross had recently seen four culprits thus exposed, one of whom was said to have lived for several days in excruciating agonies.

Daoud’s successor, one Ali Pasha, was one of those officials brought up in the Porte, who, after the abolition of the old system, were generally sent from Constantinople to govern the provinces. He was an ignorant, narrow-minded, idle, and corpulent Turk, with a thin varnish of civilization, and an affectation of European manners which distinguished the new school of Turkish statesmen and public functionaries… He thought of little else than of making money wherewith to bribe persons of influence at Constantinople, in order to retain his government for as long a period as possible. He took no interest whatever in the prosperity of the province or the welfare of its population…

In company with Mitford I called upon him. We were mounted on Arab horses with splendid trappings embroidered with gold, specially provided by the Pasha himself. We were preceded by several cawasses (armed bodyguards) on horseback in picturesque costume, carrying silver-headed maces, and by runners with staves of the same metal. A guard of Sepoys and a number of attendants on foot completed the procession. We had to force our way through the crowded bazaar, scattering the buyers and sellers, the Arabs with their vegetables and other produce of their fields, the women with their baskets of fruit and bowls of sour curds, to the right and to the left…

We ascended a flight of steps, and were ushered into a beautiful apartment, the walls and ceilings of which were adorned with exquisite designs and carved trellis work in wood, and inlaid with ivory and small mirrors. It was a chamber quite worthy of Haroun al Reshid in his prime.

The Pasha was standing ready to receive us, and after the usual ceremonies and salutations, sank down again upon the low, luxurious divan, inviting us at the same time to sit upon the chairs which had been prepared for us. He was disgustingly obese, and his appearance was rendered even more repulsive than it would otherwise have been by his costume. Unaccustomed to the heat of Baghdad, and suffering, as he informed us, greatly from it, he wore nothing but a light jacket of white linen and a pair of shalways or baggy trousers of wide dimensions, was without shoes or stockings, and his naked chest was fully exposed.

Masses of fat hung upon him. Such was the type of many Turkish functionaries, men who took no exercise, rarely left their divans and their long pipes, gorged themselves twice a day with the most fattening dishes, and thought of little but the delights of the harem. His head was small and close shaven; he constantly removed his fez to mop it with his handkerchief. His countenance was insipid, stupid, and sensual, and his small eyes and the few straggling white hairs on his chin, which served for a beard, showed that he was of real Tartar descent.

Pipes — the cherry and jessamine sticks were then still in use — and coffee were brought to us. Our conversation was limited to the usual compliments and to the stereotyped questions and answers which passed on such occasions between Turkish Pashas and European travellers. Our audience was soon brought to a close, and we took our leave, returning to the Residency. When one saw the kind of men to whom the government and welfare of the Sultan’s subjects were confided, the condition of his Empire, the signs of poverty, misery, and decay which surrounded one on all sides, could scarcely be a matter for surprise. (Autobiography, v. I, 344-349)

In Persia: seeking permission from the ‘Matamet’ in Isfahan

It was known that there were ancient ruins in the southern Zagros mountains, those of the city of Susa among them. Because it was across the Persian border Layard needed permission to enter the region. To obtain it from the regional governor, the ‘Matamet’ — a eunuch by the name of Manuchar Khan — he made his way from Hamadan to Isfahan, a violent storm striking his party en route.

I soon got wet to the skin. Except when the vivid flashes of lightning, accompanied by deafening peals of thunder, showed us surrounding objects, we were in total darkness. When the storm had ceased and we had wandered about for some time, distant lights and the barking of dogs directed us to the village of which we were in search. After scrambling through ditches and wading through water-courses, we found ourselves at the gate of a ruined khan (guest-house) where some men were gathered round a bright fire.

They were strolling shoemakers, who were on their way to Isfahan, and had taken up their quarters for the night in a vaulted passage which had afforded them shelter from the storm. Upon the fire they had kindled was a large caldron of savoury broth, which was boiling merrily. The long ride had given me an appetite, and I seated myself without ceremony in the group, and began to help myself without waiting for an invitation.

The shoemakers, although good Mussulmans, made no objection to my dipping my own spoon into the mess with them. Seeing that my clothes were soaked by the rain, and that I was suffering from ague, they very civilly left me alone in the recess in which they had established themselves, and I was able to dry myself by their fire and to spread my carpet for the night by the side of its embers.

Next day we entered upon the great plain in which Isfahan is situated, and I soon came to a broad, well-beaten track, which proved the highway from Hamadan to that city. After following it for a short distance I was so exhausted by a severe attack of fever, and by the dysentery which had greatly weakened me, that I was obliged to dismount on arriving at a small village called Tehrun, and to take a little rest. After the shivering fit had passed I resumed my journey, but being again overtaken by a heavy thunderstorm, I took refuge in a flour-mill which was fortunately hard by.

The gardens amongst which I had entered before arriving at Tehrun reach in an almost uninterrupted line to Isfahan. They produce fruit and vegetables of all kinds, especially melons of exquisite flavour, which have an unrivalled reputation throughout Persia… The many horsemen, and men and women carrying loads of produce, whom I passed on the road showed me that I was approaching Isfahan; but nothing could be seen of the city, which was completely buried in trees. By constantly asking my way I managed to reach, through the labyrinth of walls which enclose the gardens and melon beds, the Armenian quarter of Julfa…

Mr Edward Burgess, an English merchant from Tabreez, who was at Isfahan on business, hearing that I had arrived, came to see me and offered to be of use to me. He proposed that we should present outselves to the governor, Manuchar Khan, or, as he was usually called, ‘the Matamet’, to whom he was personally known. (Early Adventures, 112-114)

Layard now had his first meeting with Manuchar Khan, the much-feared Persian governor of Isfahan who was determined to humble the Bakhtiari and to put its leader in chains. Manuchar Khan, the ‘Matamet’, would have a lot to do with Layard’s fate in the next two years.

The Matamet himself sat on a chair, at a large open window, in a beautifully ornamented room at the upper end of the court. Those who had business with him, or whom he summoned, advanced with repeated bows, and then stood humbly before him as if awestruck by his presence, the sleeves of their robes, usually loose and open, closely buttoned up, and their hands joint in front — an immemorial attitude of respect in the East. (A footnote adds that ‘the attendants of the Assyrian King are thus represented in the sculptures from Nineveh.’)

In the ‘hauz’, or pond of fresh water in the centre of the court, were bundles of long switches from the pomegranate tree, soaking to be ready for use for the bastinado, which the Matamet was in the habit of administering freely and indifferently to high and low. In a corner was the pole with two loops of cord to raise the feet of the victim, who writhes on the ground and screams for mercy. This barbarous punishment was then employed in Persia for all manner of offences and crimes, the number of strokes administered varying according to the guilt or obstinacy of the culprit.

It was also constantly resorted to as a form of torture to extract confessions. The pomegranate switches, when soaked for some time, become lithe and flexible. The pain and injury which they inflicted were very great, and were sometimes even followed by death. Under ordinary circumstances the sufferer was unable to use his feet for some time, and frequently lost the nails of his toes. The bastinado was inflicted upon men of the highest rank — governors of provinces, and even prime ministers — who had, justly or unjustly, incurred the displeasure of the Shah.

Manuchar Khan, the Matamet, was a eunuch. He was a Georgian, born of Christian parents, and had been purchased in his childhood as a slave, had been brought up as a Mussulman, and reduced to his unhappy condition. Like many of his kind, he was employed when young in the public serve, and had by his remarkable abilities risen to the highest posts. Considered the best administrator in the kingdom, he had been sent to govern the great province of Isfahan, which included within its limits the wild and lawless tribes of the Lurs and the Bakhtiari, generally in rebellion, and the semi-independent Arab population of the plains between the Luristan Mountains and the Euphrates.

He was hated and feared for his cruelty; but it was generally admitted that he ruled justly, that he protected the weak from oppression by the strong, and that where he was able to enforce his authority life and property were secure. He was known for the ingenuity with which he had invented new forms of punishment and torture to strike terror into evil-doers, and to make examples of those who dared to resist his authority or that of his master the Shah, thus justifying the reproach addressed to beings of his class, of insensibility to human suffering.

One of his modes of dealing with criminals was what he termed ‘planting vines.’ A hole having been dug in the ground, men were thrust headlong into it and then covered with earth, their legs being allowed to protrude to represent what he facetiously called ‘the vines.’ I was told that he had ordered a horse-stealer to have all his teeth drawn, which were driven into the soles of his feet as if he were being shod. His head was then put into a nose-bag filled with hay, and he was thus left to die. A tower still existed near Shiraz which he had built of three hundred living men belonging to the Mamesenni, a tribe inhabiting the mountains to the north of Shiraz, which had rebelled against the Shah.

They were laid in layers of ten, mortar being spread between each layer, and the heads of the unhappy victims being left free. Some of them were said to have been kept alive for several days by being fed by their friends, a life of torture being thus prolonged. At that time few nations, however barbarous, equaled — none probably exceeded — the Persian in the shocking cruelty, ingenuity, and indifference with which death or torture was inflicted. (Early Adventures, 115-117)

Among the Bakhtiari

After the Matamet gave his permission to visit this part of Persia, Layard was delayed for five weeks: the men who were to accompany him into the world of the Bakhtiari tribes were in no hurry to leave Isfahan. During this period he familiarized himself with the Persian language and acquired the Bakhtiari costume he wore over the months to come.

The day after my interview with the Matamet I succeeded, after some trouble, in finding Shefi’a Khan, who had promised to introduce me to Ali Naghi Khan, the brother of the principal chief of the Bakhtiari tribes. They both lodged in the upper story of a half-ruined building forming part of one of the ancient royal palaces. The entrance was crowded with their retainers — tall, handsome, but fierce-looking men, in very ragged clothes. They wore the common white felt skull-cap, sometimes embroidered at the edge with coloured wools when worn by a chief, their heads being closely shaven after the Persian fashion, with the exception of two locks, called ‘zulf,’ one on each side of the face.

The Bakhtiari usually twist round their skull-caps, in the form of a turban, a long piece of coarse linen of a brown colour, with stripes of black and white, called a ‘lung,’ one end of which is allowed to fall down the back, whilst the other forms a topknot. In other respects they wear the usual Persian dress, but made of very coarse materials, and, as a protection against rain and cold, an outer, loose-fitting coat of felt reaching to the elbows and a little belong the knees. Their shoes of cotton twist, called ‘giveh,’ and their stockings of coloured wools, are made by their women.

A long matchlock — neither flint-locks nor percussion-caps were then known to the Persian tribes — is rarely out of their hands. Hanging to a leather belt round their waist, they carry a variety of objects for loading and cleaning their guns — a kind of bottle with a long neck, made of buffalo-hide, to contain coarse gunpowder; a small curved iron flask, opening with a spring, to hold the finer gunpowder for priming; a variety of metal picks and instruments; a mould for casting bullets; pouches of embroidered leather for balls and wadding; and an iron ramrod to load the long pistol always thrust into their girdles. I have thus minutely described the Bakhtiari dress as I adopted it when I left Isfahan, and wore it during my residence with the tribe.

The five weeks that I passed in Isfahan were not unprofitably or unpleasantly spent. I continued to study the Persian language, which I began to speak with some fluency. I frequently visited the mosques (into which, however, I could not, as a Christian, enter), and the principal buildings and monuments of this former capital of the Persian kingdom now deserted by the court for Tehran. I was delighted with the beauty of some of these mosques, with their domes and walls covered with tiles, enameled with the most elegant designs in the most brilliant colours, and their ample courts with refreshing fountains and splendid trees.

I was equally astonished at the magnificence of the palaces of Shah Abbas and other Persian kings, with their spacious gardens, their stately avenues, and their fountains and artificial streams of running water, then deserted and fast falling to ruins. It was not difficult to picture to oneself what they must once have been. Wall-pictures representing the deeds of Rustem and other heroes of the ‘Shah-Nemeh,’ events from Persian history, incidents of the chase and scenes of carouse and revelry, with musicians and dancing boys and girls, were still to be seen in the deserted rooms and corridors, the ceilings of which were profusely decorated with elegant arabesques… In the halls, the pavements, the paneling of the walls, and the fountains, were of rare marbles inlaid with mosaic… These gorgeous ruins — desolate and deserted — afforded the most striking proof of the luxury and splendour of the Persian court in former times…

But the most characteristic and curious scenes of Persian life were those I witnessed in the house of a Lur chief who had left his native mountains and had established himself in Isfahan, professing to be a ‘sufi,’ or free-thinker. He invited me more than once to dinner, and I was present at some of those orgies in which Persians of his class were too apt to indulge. On these occasions he would take his guests into the ‘enderun,’ or women’s apartments, in which he was safe from intrusion and less liable to cause public scandal. They were served liberally with arak and sweetmeats, whilst dancing girls performed before them.

Many of these girls were strikingly handsome — some were celebrated for their beauty. Their costume consisted of loose silk jackets of some gay colour, entirely open in front so as to show the naked figure to the waist; ample silk ‘shalwars,’ or trousers, so full that they could scarcely be distinguished from petticoats, and embroidered skullcaps. Long braided tresses descended to their heels, and they had the usual ‘zulfs,’ or ringlets, on both sides of the face. The soles of their feet, the palms of their hands, and their finger- and toenails were stained dark red, or rather brown, with henna. Their eyebrows were coloured black, and made to meet; their eyes, which were generally large and dark, were rendered more brilliant and expressive by the use of ‘kohl.’

Their movements were not wanting in grace; their postures, however, were frequently extravagant, and more like gymnastic exercises than dancing. Bending themselves backwards, they would almost bring their heads and their heels together. Such dances are commonly represented in Persian paintings, which have now become well known out of Persia. The musicians were women who played on guitars and dulcimers. These orgies usually ended by the guests getting very drunk, and falling asleep on the carpets, where they remained until sufficiently sober to return to their homes in the morning. (Early Adventures, 118-125)

Living with the Bakhtiari. Given the reputation of the Bakhtiari for treachery, cruelty, and murder, Layard pondered how he would manage life among them. After some days of difficult travel over mountain trails he arrived at Kala Tul, the fortress of their chieftain Mehemet Taki Khan.

As I rode along I could abandon myself to my reflections, which were of a very mixed kind. I was much elated by the prospect of being able to visit a country hitherto unexplored by Europeans, and in which I had been led to suppose I should find important ancient monuments and inscriptions. It would have been impossible to have undertaken the journey under better auspices. Shefi’a Khan seemed well disposed towards me. I had every reason to believe that during our intercourse at Isfahan I had gained his friendship, by various little services which I was able to render him.

As he had earlier served for a short time in a regiment of regular troops organized by English officers in the Persian service, and had thus acquired some knowledge of Europeans, he did not look upon them, as ignorant Persians did in those days, as altogether unclean animals, with whom no intercourse was permitted to good Mussulmans. His wild and lawless followers were kind and friendly to me, and I had no cause to mistrust them. But the Bakhtiari bear the very worst reputation in Persia. They are looked upon as a race of robbers — treacherous, cruel, and bloodthirsty. Their very name is held in fear and detestation by the timid inhabitants of the districts which are exposed to their depredations. I had been repeatedly warned that I ran the greatest peril in placing myself in their hands, and that although I might possibly succeed in entering their mountains, the chances of getting out of them again were but few.

However, I was very hopeful and very confident that my good fortune would not desert me, and that by tact and prudence I should succeed in coming safely out of my adventure. I determined at the same time to conform in all things to the manners, habits, and customs of the people with whom I was about to mix, to avoid offending their religious feelings and prejudices, and to be especially careful not to do anything which might give them reason to suspect that I was a spy, or had any other object in visiting their country than that of gratifying my curiosity and of exploring ancient remains. Accordingly I abstained from making notes or taking observations with my compass except when I could do so unobserved. Whilst associating with my companions on intimate terms, and conversing freely with them, I abstained from touching their food and their drinking vessels unless invited to do so, and from showing too much curiosity and asking too many questions about their country, its resources, and the roads through it.

On waking one morning I found that my quilt had been stolen. This was a severe loss, for, although the weather was still mild during the day, the nights were cold, as it was now the 3rd of October. I was not the only sufferer from the thievish propensities of our hosts. We had another most fatiguing days’ journey, scrambling over stony and almost inaccessible mountain ridges, or forcing our way through the thickets of myrtle, oleander, and tamarisk which clothe the banks of the Karun in this part of its course. The mountain slopes were clothed with a kind of heath or heather in full bloom, bearing flowers of the brightest rose colour.

Two tracks led to Kala Tul — the castle of Tul — where Mehemet Taki Khan was then residing. One track followed the course of the river and crossed the plain of Mal-Emir, the other took a direct line across the mountains. We passed through a hamlet called Sheikhun, surrounded by pomegranate trees in full fruit, but deserted at this time of the year by its inhabitants, who were living higher up on the mountain side. The chief of Sheikhun, who received Shefi’a Khan and his followers with the warmest expressions of friendship, embracing them all round, was an immediate retainer of the great Bakhtiari chief. As he could not persuade them to pass the night in his encampment, he insisted that they should remain to breakfast. He slew a sheep for them, and brought us a great bowl of sour milk and delicious honeycombs.

We reached our night’s quarters after a most toilsome and dangerous climb. We had now entered the district of Munghast, and had reached a high elevation. The air was keen and piercing, and I had good reason to lament during a bitterly cold night the loss of my wadded quilt… After scrambling and crawling down a most precipitous descent — men and horses appearing to those below them as if piled up one upon the other — we came to a narrow ravine formed by a torrent now dry. Making our way over the loose stones and boulders in its bed, we issued into a small plain, and saw, high up on a mound at a short distance from us, the castle of Tul — the end of our long and weary journey. (Early Adventures, 131-144)

In the Fortress of Kala Tul. The chieftain Mehemet Taki Khan was away when Layard arrived at his castle, so he was formally received by the Khan’s first wife, Khatun-jan Khanum. She told him that her son was gravely ill with fever, and when the boy’s illness worsened she urgently sent for her husband to return. Together, the Khan and his wife implored Layard to try and effect a cure.

My reputation as a Frank (i.e., European) physician had preceded me, and I had scarcely arrived at the castle when I was surrounded by men and women asking for medicines. They were principally suffering from intermittent fevers, which prevail in all parts of the mountains during the autumn. Shortly afterwards the chief’s principal wife sent to ask me to see her son, who, I was told, was dangerously ill, and I was taken to a large booth constructed of boughs of trees, in which she was living. It was spread with the finest carpets, and was spacious enough to contain a quantity of household effects heaped up in different parts of it.

The lady sat unveiled in a corner, watching over her child, a boy of ten years of age, and about her stood several young women, her attendants. She was a tall, graceful woman, still young and singularly handsome, dressed in the Persian fashion, with a quantity of hair falling in tresses down her back from under the purple silk kerchief bound round her forehead. As I entered she rose to meet me, and I was at once captivated by her sweet and kindly expression.

She welcomed me in the name of her husband to Kala Tul, and then described to me how her son had been ill for some time from fever, and how two noted practitioners of native medicine had been sent for from a great distance to prescribe for him, but had failed to effect a cure. She entreated me, with tears, to save the boy, as he was her eldest son, and greatly beloved by his father. I found the child very weak from a severe attack of intermittent fever. I had suffered so much myself during my wanderings from this malady that I had acquired some experience in its treatment. I promised the mother some medicine and told her how it was to be administered… The condition of the boy, however, became so alarming that his father was sent for.